Helprin’s work is informed by a childhood spent in Ossining, New York, along the Hudson River (also the hometown of John Cheever), the British West Indies, and life chapters that unfolded.

A Harvard and Oxford alum, with post-graduate studies at Columbia and Princeton, he served in the British Merchant Navy, the Israeli Infantry and Air Force. And in addition to English, he can chat or read in French, Italian, Arabic, German, and Hebrew. The accolades he’s achieved reach skyward: He is a fellow of the American Academy in Rome and a former Guggenheim Fellow; he won the National Jewish Book Award and the prestigious Prix de Rome from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Currently he is a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute. Winter’s Tale, which Helprin wrote in 1983, is thought by many to be one of the best works of American fiction of its day.

A Founding Landscape

His interest in Virginia was piqued, when, at the age of seven, he visited Civil War battlefields on a family road trip south. From New York to Virginia, as far south as Savannah and back through Maryland—and this was before the days of interstate highways—young Helprin checked off as many sites as his family could squeeze in. They also visited Charlottesville, when a visit to Monticello isn’t what it is now. “You could just go in, wander around, and sit in Jefferson’s chair,” he recalls.

Now, decades later, with an illustrious 50-year writing career that includes books, short story collections, and children’s books, the way Helprin sees it, Virginia has given us the greatest political gifts the world has ever seen: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

The Genius of Mark Helprin

Helprin says that the landscape and culture were central to the commonwealth’s founding, where Virginians had an intimate relationship with nature and the land and where there were no apparent limits and endless freedom. Leaders were educated. They were patient men, who wrote and thought “with elegant, measured genius,” he says, to create an independent republic based on the English language and on law and traditions but far away and distinct from England, “with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence.”

In First Things, a print and online journal of religion and public life, Helprin contributed “By Starlight Undiminished” in the November 2017 edition, in which he elaborates on the ways the American landscape shaped the nation’s founding. His writing is brilliant and eloquent, where the reader must take a breath every few paragraphs for the words to marinate. “When an American looked toward the vast expanse of his continent, whether north, south, or west,” Helprin wrote, “he saw only potential, only open land to which he knew no limit.” This was in sharp contrast to the European experience, for example, “where every space was taken.”

Blue Ridge Inspiration

So it’s actually fitting that this meticulously organized, creative, analytical, global nomad of a classical scholar chose to settle in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Helprin writes, farms, and finds inspiration at “Windrow,” where he lives with his wife, Lisa (Kennedy), on 56 rolling acres in Albemarle County. Citing Charlottesville’s landscape, economy, climate, fantastic medical care at UVA, and other resources at the University of Virginia, Helprin puts it ahead of many cities. The Helprins also chose Virginia to provide the best possible education for their two daughters.

Their property is on a picturesque, winding mountain road, off Route 29—the part dedicated to the heroic Maryland/Virginia 29th Infantry Division who participated in the D-Day invasion of World War II. When I visit in the summer, I see field upon field of tall, sweet corn and soybeans, and pass nearly a dozen wineries in the Monticello American Viticultural area.

Writing at Windrow

The Genius of Mark Helprin

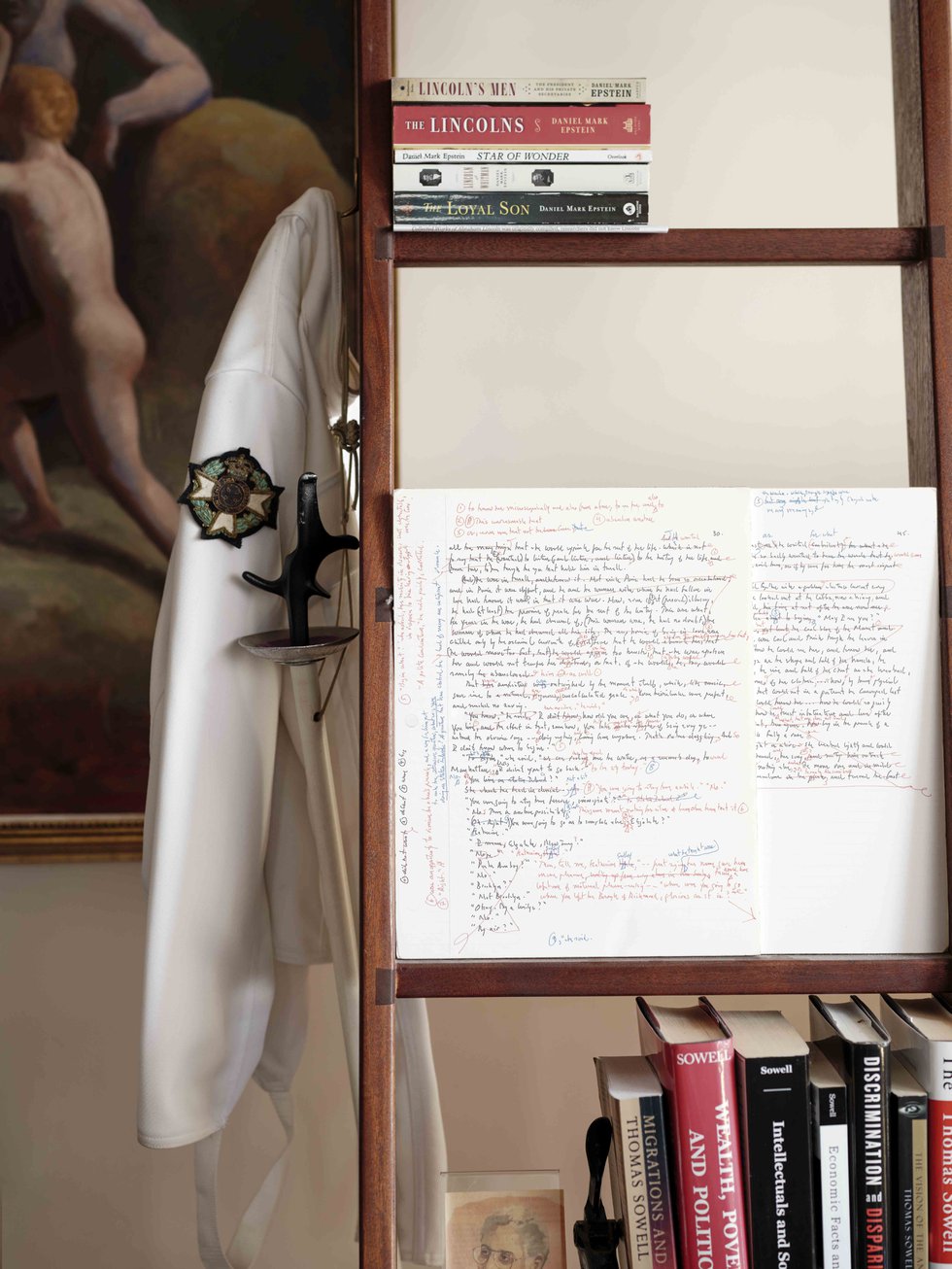

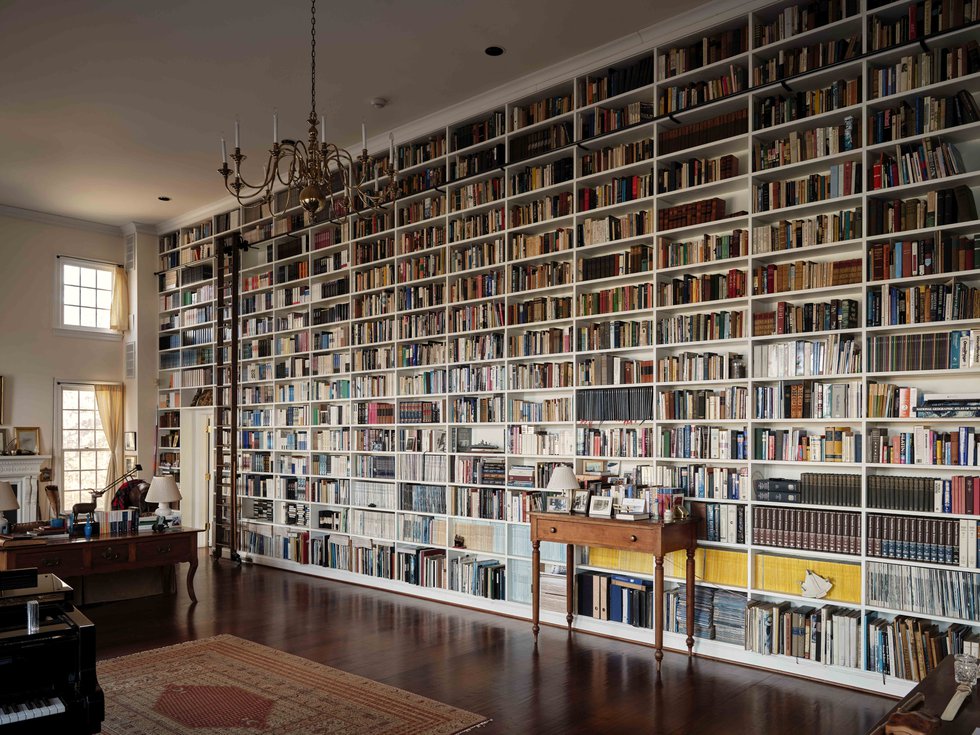

Windrow is a three-story red brick classic Georgian home with green hedges framing the entrances. Furnished with antiques, paintings, family photographs, and portraits, it’s also—naturally—home to thousands of books. Lots of military technical manuals and strategic assessments are in Helprin’s library, which spans nearly 50 feet and is almost two stories high. A rolling ladder helps him access books otherwise unreachable, and he identifies titles with an eyeglass.

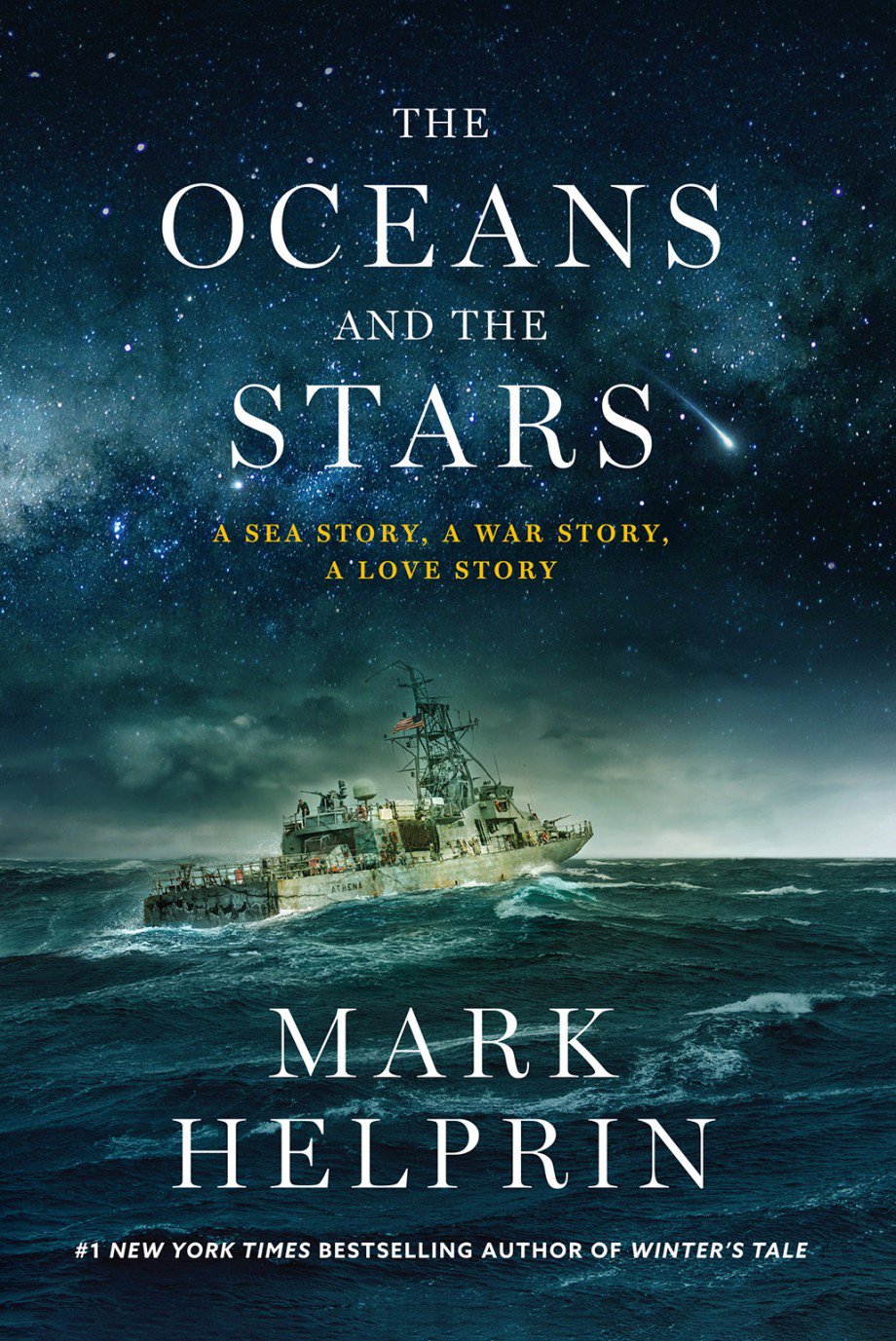

Helprin writes in longhand—usually with a Uniball pen—on one of the two sprawling desks positioned at either end of his study. His exhaustive research takes the forms of notes and documents in marked files that live on a rolling cart. And Windrow is where Helprin has penned five of his 15 published books—Freddy & Frederika, Digital Barbarism, A Writer’s Manifesto, In Sunlight and in Shadow, Paris in the Present Tense, and, his most recent, The Oceans and the Stars, which Abrams, his publisher, released in October.

The Genius of Mark Helprin

With a staggering aptitude for details, colors, impressions, settings, and events from his kaleidoscopic background and fertile mind, he carefully weaves them into the lives of the characters he creates to impart truth and universal values. He builds character into his protagonists, and they’re characters built on reason and reverence, bravery and love, humility and insight, caution and risk.

Pacing in a Helprin book is measured, not rapid. It requires time and dedication and sometimes rereading to grasp, absorb, and internalize all the nuances in a transformational voyage.

Life on a Farm

There are miles of fences on Helprin’s property, and from his dining room window, there is a clear line-of-sight for miles with the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah National Park in the distance. No man-made structures to obscure the view—as if the clock turned back. Life at Windrow can resemble a colonial wilderness. Which is just how Helprin likes it.

There, Helprin grows hay and maintains the farm himself. Long rows of trees are on the property, and when one falls, he cuts it into logs, and moves them away with a grapple—a forked implement attached to his tractor—for warm fires later. Lisa says that her husband can fix anything. Windrow is a working farm, and after harvesting hay, the Helprins share their bounty with the local Mennonite community.

The Genius of Mark Helprin

But writing remains a priority. He reads widely every day, including many newspapers, and may write up to three hours straight—“it passes very quickly,” he says. Or he may spend several hours editing before tackling farm chores. He edits in small sentences written on large sheets of paper in red ink above and below the sentences. He says it may take up to five years from when he starts writing to publication of a book. There may be up to 12 edits—eight of his and possibly four more from editors.

The notion of imagery is of great concern to Helprin. He says it and marginalizing religion are the routes to passivity. “The image has conquered the word,” he told the writer and commentator Richard Reinsch in a 2023 article for The Heritage Foundation, adding that computer screens, smart phones, and now social media has changed in many ways the nature of people. “Compression of information, movement, picture, color, sound, transmission—all this moving at a fast pace has allowed for the image to conquer the word. “People are now addicted to images; they do not appreciate the word.”

Lighting His Own Way

He’s compared to the greats of literature. His friend, the late William F. Buckley, Jr., thought he should win the Nobel Prize. “He is closer to Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas than any writer I know,” gushed the founder and publisher of National Review, still the country’s leading conservative magazine. “Joyce and Nabakov could produce verbal astonishments as readily. Not many others come to mind,” said Time Magazine. In addition to being a writer, the multi-faceted Helprin is a defense analyst, a speech writer, and a foreign affairs expert. He’s called genius, lyrical, thrilling, and astonishing—the superlatives cascade from all corners of the world.

The Genius of Mark Helprin

The Genius of Mark Helprin

This hard-to-label maverick strenuously objects to being pigeon-holed into a trend or genre or movement. In a New York Times interview, Helprin said that he’s always detested people running in packs. “If they run in packs, I run against those packs,” he told Paul Alexander in that 1991 article. His website says it best: “Mark Helprin belongs to no literary school, movement, tendency, or trend. As many have observed, and as Time Magazine has phrased it, ‘He lights his own way.’”

John William Van de Kamp is a retired Air Force Colonel. A graduate of the Air Force Academy and Creighton University, he served in the Strategic Air Command and the Pentagon and State Department in national security strategy. He has also served as an opinion columnist for the Annapolis Capital Gazette.