Methods for curing tobacco may have modernized, but family recipes remain fiercely guarded.

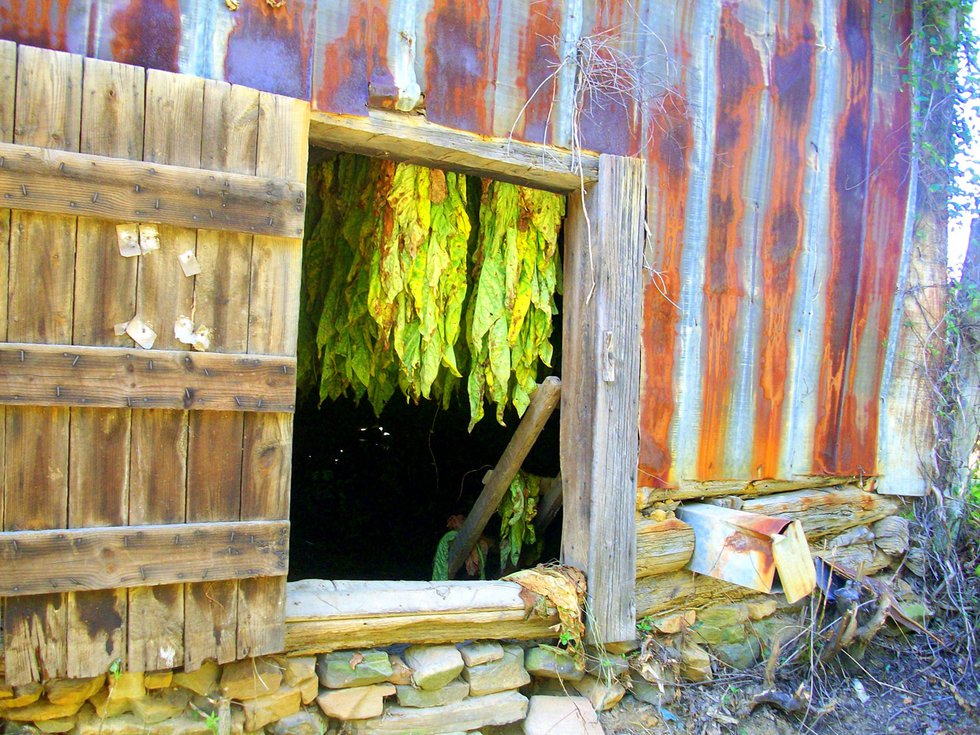

Tobacco ready for flue-curing.

Photo by Sonja Ingram, courtesy of Preservation Virginia

Phillip Morris factory in Richmond, modern-day.

Photo courtesy of Phillip Morris, VA

For centuries, tobacco curing methods were like secret family recipes passed down from generation to generation. “When it came time, my grandfather taught my father how to do it and the same was true for me,” says 89-year-old Hart Hudson of South Hill, whose family has raised tobacco for generations. “Each family had their own way of doing it and you felt your method made your tobacco the best … The most demanding and memorable part was that you had to be out at the barns all day and night feeding wood into the furnace making sure the heat stayed just-so.”

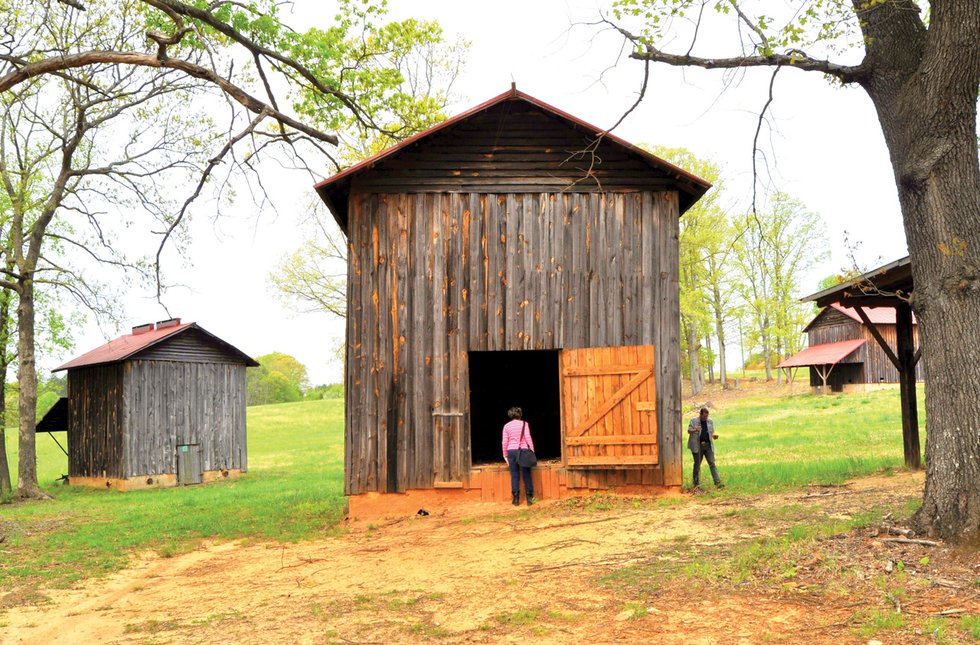

The process began when leaves were harvested in August and September. Gathered in long rectangular crates known as slides and dragged to the tobacco barn by mules, the loose leaves were strung by the stalks and hung horizontally in bundles along stakes, which would in turn be hung from a tiered series of poles crossing the width of the barn. Then it was time for the heat.

“The flue-cured tobacco barns had a big external furnace attached to pipes that carried heat through the building without filling it with smoke,” explains Leonard Smith, curator of the South Hill Tobacco Farm Life Museum. A popular method was to heat the interior to 115 degrees for the first day, which would slowly change the color of the leaves from bright green to a rich golden brown. Once the color was right, the heat would increase to around 175 degrees. This cooked the sap out of the stems, which meant the leaves were finished.

The process lasted 3-7 days, depending on the farmer. “During that time they’d gather socially around the barn, fixing stews and roasted potatoes and serving treats like apples or watermelon,” says Smith. “When the harvest had been good, the event was very celebratory in nature.”

But in the 1970s, advances in technology brought big changes. Today, with most family farms now gone and those that remain having modernized, come curing time the scene is very different. Leaves are transported from the fields via tractor whereupon racking machines arrange them for hanging in lines in prefabricated metal trailers equipped with high-efficiency digitally-controlled heaters. Once loaded, apps keep farm managers, owners and other personnel aware of conditions inside the curing chambers. And as heat levels are adjusted by computer, temperature is never a matter of guesswork.

But Hudson doesn’t miss the old methods. Not at all. “You were always worried about the barn catching fire and burning half your harvest,” he says. “Nowadays I sleep in my bed at night and check my phone. If we want to get together, we get together at the house and celebrate without all that hassle.”

Bright Leaf Legacy

Click here to read more about the past, present and future of Virginia’s tobacco industry.