The past, present and future of Virginia’s tobacco industry.

A tobacco field near Danville.

Tobacco field and barn.

Photo courtesy of Preservation Virginia

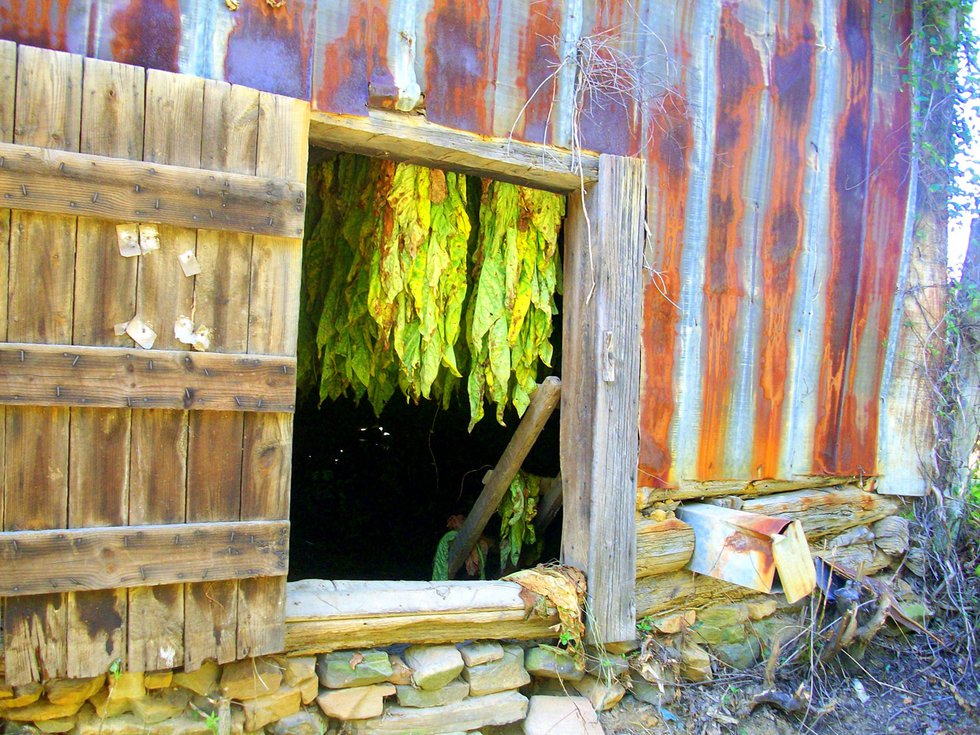

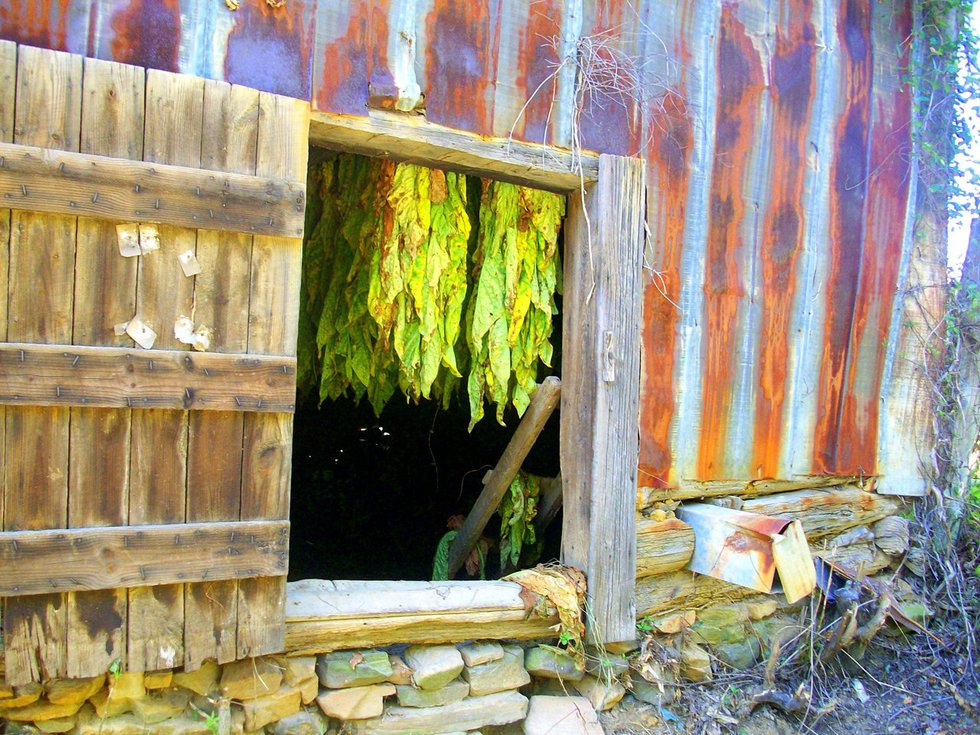

Tobacco ready for flue-curing.

Photo courtesy of Preservation Virginia

Old farm implements like these are on display at the Tobacco Farm Life Museum in South Hill.

Photo courtesy of Preservation Virginia

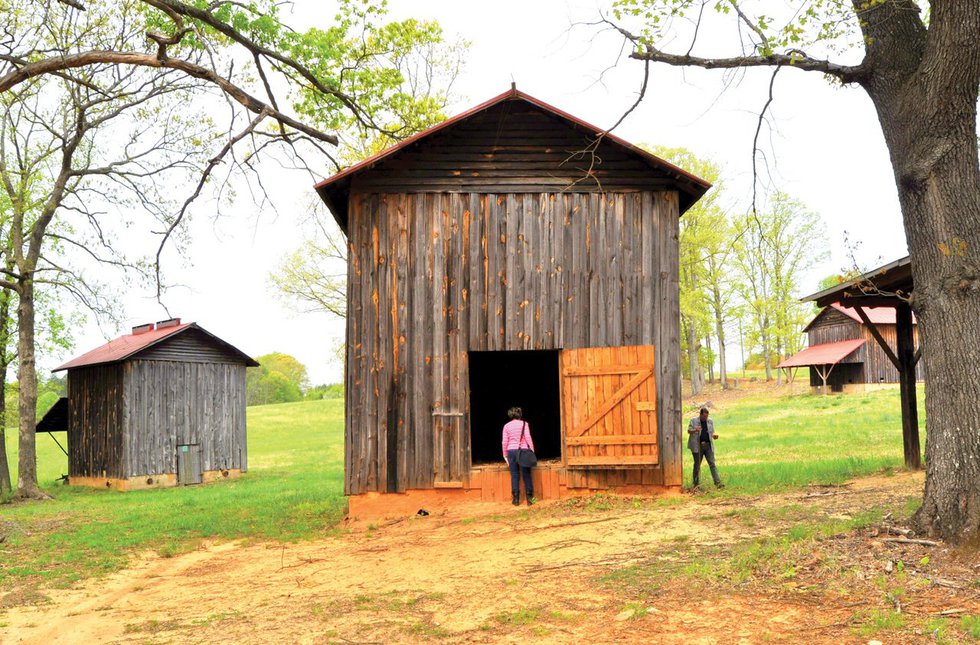

The Tobacco Barn Preservation Project has revitalized 45 barns in Virginia and North Carolina.

Photo courtesy of Preservation Virginia

As I pull open the big wooden doors of the Tobacco Farm Life Museum in South Hill and step into the dimly lit interior of its first floor, 55-year-old museum curator Leonard Smith greets me. Hailing from Lynchburg, which was once known as “Tobacco City,” the historian is tall, and smiles kindly from behind a pair of spectacles.

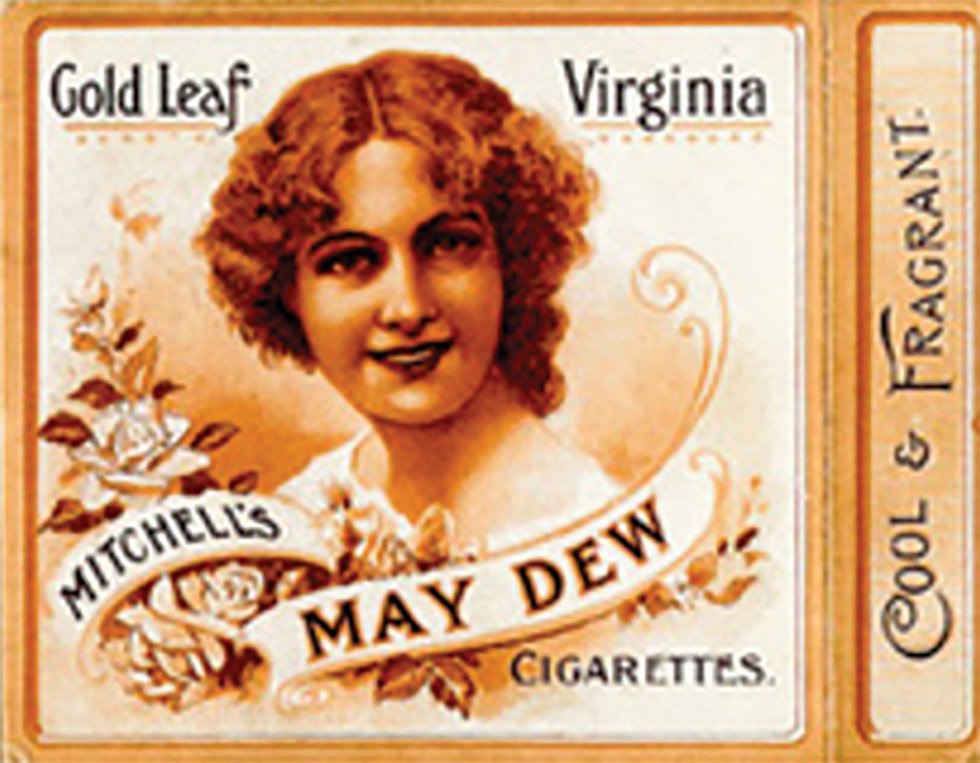

He leads me across salvaged wide-plank flooring polished to a warm sheen and over to a bank of glass display cases filled with 19th- and early 20th-century smoking pipes, historical photos and press clippings, tobacco ads from the antebellum period to the early 1980s, and pastiches of cigar, cigarette and chewing tobacco packaging featuring an array of stoic American Indians.

Antiques. Relics. These carefully preserved items suggest that the industry they recall—one that helped make this railroad town a booming hub of tobacco production—is no more.

And yet, nothing could be further from the truth. Last year, 22,000 acres of farmland produced 48 million pounds of flue-cured tobacco in Virginia. Tobacco ranked among the state’s top 10 agricultural products—our leading industry—and Virginia is one of the top states in overall production, coming in third only behind North Carolina and Kentucky.

And less than five miles from here is one of the state’s largest tobacco producers, R. Hart Hudson Farms, which has been in business for more than 80 years.

The First Cash Crop

“Of course, the natives were growing tobacco in this part of the world well before the possibility of a colony was ever considered,” explains 58-year-old Glenn Hudson of South Hill who, with his father, Hart Hudson, co-owns R. Hart Hudson Farms. “But it was John Rolfe who made tobacco America’s crop. And in a very real sense we’re a product of that legacy.”

As our Virginia history books tell us, after the 1607 English colonization of Jamestown, it was Rolfe who obtained seed stock from a popular Spanish variety of tobacco, Nicotiana tabacum. After establishing Varina Farms in 1612, he became the first grower in North America to successfully cultivate tobacco as an export crop, breaking what had previously been a Spanish monopoly on the European market. Rolfe’s achievement laid the groundwork for a booming agricultural economy in the colony based around tobacco.

By 1617, more than 20,000 pounds of tobacco were being exported to England, with that number doubling the very next year. Equally as dark and sweet, and yet milder and more delicate than Spanish-grown leaves, in less than a decade Virginia tobacco became the European standard. In a 1619 effort to maintain brand control and keep pace with demand, the Virginia General Assembly voted to implement inspection standards, fix prices at 3 shillings per pound and establish ports and warehouses to facilitate the trade, giving rise to cities, including Alexandria, Lynchburg, Norfolk and Richmond.

“How tobacco got to this part of the state and elsewhere was through soil depletion in the Tidewater,” explains Leonard Smith. “It’s a nutrient intensive crop and back then, without proper crop-rotation science, farmers rapidly exhausted the soil. As yields fell, they moved their operations westward.”

By the time of the Revolutionary War, Virginia was exporting around 55 million pounds of tobacco per year from farms distributed throughout the colony, and, while records are imprecise, had imported a labor force of more than 200,000 African slaves to work its many plantations. Smaller farm owners relied largely on indentured servants for labor; about 50,000 arrived in the colony between 1630 and 1680 alone.

War Brings Changes

But the Revolution changed everything. During its first year, despite the fact that the war effort was funded by tobacco profits, the state grew less than 25 percent of its former yield, producing just 14.5 million pounds of tobacco.

According to historian Herbert B. Adams, author of A History of the Tobacco Industry in Virginia from 1860 to 1894, published in 1897, who prefaces his book with a look at the development of the industry, the main force behind the shift had to do with the fact that, during the war, faced with the sudden scarcity of cross-Atlantic imports, European nations were forced to develop their own systems of tobacco cultivation or seek out other sources. As such, in 1820, Virginia exported just shy of 600,000 pounds of tobacco. It would take decades to recover the momentum begun in Colonial times, but business did steadily increase, and by 1860, although the crop was no longer the state’s biggest agricultural product (cotton and wheat were at that time in high demand), on the eve of the American Civil War exports totaled around 17.1 million pounds.

The Civil War disrupted tobacco production in the South, with farms shifting to food production and later, the abolition of slavery. But tobacco didn’t die—quite the contrary.

The Dawn of Big Tobacco

“Cigarettes had been introduced during the Crimean War [1853-1856] after English soldiers encountered Turks smoking, and they eventually caught on with U.S. factory workers,” explains Leonard Smith. “Up until then, you smoked tobacco through pipes, used snuff, chewed, or, to a lesser extent smoked cigars.” But cigarettes introduced Americans to a lighter smoke they could inhale more deeply, and it offered a more immediate nicotine rush. Increased use led to increased demand.

In 1940, the American Model Tobacco Company, in business from 1939 to 1985, completed the building that has become an art deco landmark on Jefferson Davis Highway in Richmond.

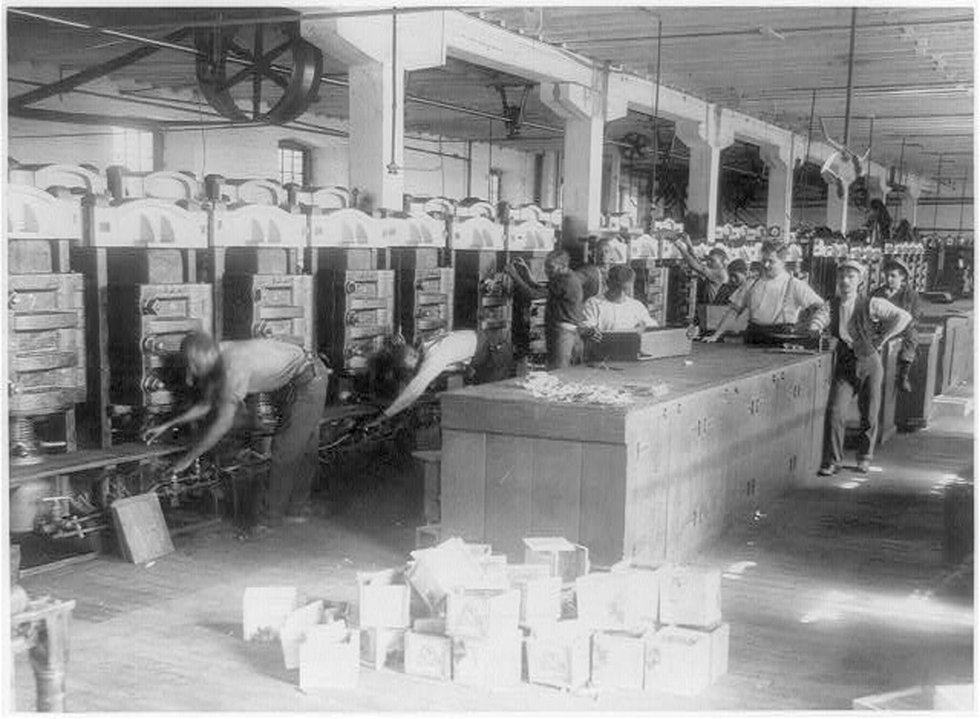

Men sort tobacco boxes in Richmond, around 1900.

Women sort tobacco at T.B. Williams Tobacco Co. in Richmond, around 1900.

Tobacco parade, around 1930.

Tobacco girls.

The invention of the automated roller in 1881 by James Bonsack of Roanoke County facilitated a boom in the industry. “The significance of that invention cannot be over-emphasized,” says Glenn Hudson. “Suddenly you went from a warehouse of people hand-rolling cigarettes to having machines that could roll 200 cigarettes a minute, which changed everything.”

Leading the way was Durham, North Carolina-based tobacco baron James Buchanan “Buck” Duke. After striking a secret deal with Bonsack in 1884 that enabled him to buy the rolling machines cheaply and gave him exclusive rights to service them, Duke was able to sell at a lower price and thereby seize nearly half of the cigarette trade within just a few years. Duke had bought five major companies by 1890—including Richmond’s Allen & Ginter—and incorporated them under the name American Tobacco Company, which marked the beginning of “Big Tobacco.” In the 1880s, according to U.S. Agricultural reports, Virginia farmers were churning out nearly 90 million pounds of the crop each year.

There were 77 factories and 11,000 people employed by the tobacco industry in Richmond alone.

After spending a staggering $800,000 on advertising in 1889 (which would equate to something like $20.63 million in 2017), ATC grew to produce around 90 percent of the nation’s cigarettes. Over the course of the next two decades, the company continued to grow, absorbing as many as 250 additional rival businesses (among them, Richmond’s Lucky Strike Company) and, on top of growing its equity to $316 million (around $7.8 billion in today’s dollars), was producing 80 percent of all of the tobacco products in the U.S., including cigarettes, plug tobacco, smoking tobacco and snuff.

Antitrust lawsuits broke up the ATC monopoly in 1911, and in Virginia, this led to the formation of new entities that are still in business today, including Richmond’s Universal Leaf Tobacco Company.

Formed in 1918 when tobacco merchant Jaquelin P. Taylor of Orange County merged with five other prominent merchants, Universal Leaf—now a subsidiary of Universal Corporation—is presently the largest leaf tobacco dealer in the world. Headquartered in Richmond, ULT purchases, processes and stores leaf tobacco for later sale to tobacco product manufacturers, and maintains facilities on five continents, doing more than $2 billion worth of business in 30 different countries each year and employing around 24,000 workers worldwide.

One of ULT’s largest customers is Henrico County-based Altria Group, parent company of, among others, cigarette manufacturer Phillip Morris USA. Today, Altria is one of the world’s largest tobacco companies, employing around 3,800 Virginians, and a total of around 8,000 across the country. The company currently manufactures about half of all the cigarettes produced in the U.S., and while it processes Virginia-grown tobacco, its cigarettes are also made with tobacco from other countries, including Brazil, China, Turkey and Zimbabwe. Overall, 28 tobacco manufacturing companies currently operate in Virginia.

Despite a huge decline in tobacco use in the U.S.—in the late 1960s, around 66 percent of Americans were habitual smokers compared to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that put that number around 16 percent today—tobacco is still a very profitable business. In 2015, the U.S. produced 489 million pounds of flue-cured tobacco. With a USDA estimated price of $1.87 per pound, the crop’s value is approximately $917 million. (Approximately 30 percent of that crop was sold to domestic markets, and the rest to other countries.)

Legacy Farmers

“My father bought the farm we’re standing on at auction during the Depression and at that time there was a big sign in downtown South Hill that read ‘Tobacco is Gold,’” reflects 89-year-old Hart Hudson, who says his people have been farming tobacco for so many generations he would have to consult the family Bible to put a number on it. “That sign was there because everyone who lived here had something or another to do with tobacco. Tobacco was the town’s business, and back then your life didn’t just revolve around it, it was your life.”

Hart Hudson at his farm in South Hill.

Photo by 621 Studios

Despite increasing mechanization, the actual process of farming tobacco remained extremely labor-intensive, requiring yearlong around-the-clock attention. “In the early and even mid-20th century, farmers were still doing most everything by hand,” explains Smith, retrieving from the Tobacco Farm Life Museum’s collections what looks to be a foot-long 2.5-inch thick vampire stake with a small cylindrical pole jutting from its side about six inches above its blunted point. “You’d have a horse or a mule that you’d use to plow the field and get the rows arranged, then you’d use a device like this for planting.” The farmer and his family—even kids, regardless of age—would don seed sacks and make their way through the rows in teams of two, the first on bended knee plunging his or her stick into the ground up to the rod and dropping in a few seeds, the second covering the holes over with dirt and adding water. As you can imagine, planting in this manner was a time-consuming process.

“In those times, Mecklenburg County refused to make school attendance mandatory, and during the harvest or planting season many students didn’t show up,” says Smith. “Most families felt if a kid made it to the eighth grade or so that was education enough, as it was more important to have them home on the farm. Summer vacation coincided with the growing season for a reason, because it would have been pointless for teachers to open the doors.”

Farming Then and Now

Turning off pastoral field- and forest-lined Tobacco Lane onto the long gravel drive of R. Hart Hudson Farms, it’s almost unfathomable that world ever existed. In the place of graying wooden tobacco barns once used for curing are huge tin-roofed pavilions covering row after row of what look to be big-rig trailers equipped with furnaces and tin chimneys, which now cure the tobacco.

“When I was a teenager, and it came time to cure the tobacco we’d have to be at the barns all night long and for days on end, feeding the furnace and making sure it stayed hot enough in there to cure the crop but not catch the building on fire,” says Hart Hudson, who with his wife Catherine raised their three children on the farm. “Now everything is computerized. If I need to, I can adjust the temperature of a curing unit while I’m at the grocery store using my phone!”

Plants begin in Hudson’s 12 half-football-field-long hoop houses: “Nowadays we start all the plants inside, and after about a month we transplant them into the fields,” he says, waving a hand over a sea of bright green seedlings of varieties with names like CC 65, NC 196, NC 299 and GL 395 that have been selectively bred and genetically tweaked to be resistant to disease, droughts and pests, and to mature earlier or later, or not flower at all.

Working closely with researchers and agricultural extension agents, farm manager David Trujillo—Hudson’s son in law—has perfected growing methods to the point where, on top of managing complex multi-year rotation schedules, he staggers different plantings according to developmental stages and harvest times, making the crop more manageable.

“As opposed to having hundreds of acres maturing at one time, farmers plant different varieties to maximize efficiency by spreading out processes like cutting the flowers, removing unwanted leaves and harvesting over the course of many weeks,” says Virginia Tech agricultural extension office agronomist and tobacco expert David Reed.

“No matter how advanced the technology, tobacco is still a very labor-demanding crop.”

In the past, after harvest, Virginia farmers would ship by truck their cured crop to a warehouse located in places like South Hill, Petersburg or Danville, where an auctioneer would sell it to leaf merchants by the graded bundle. Today, farmers contract directly with companies like Universal Leaf, which then sells the product to manufacturers. “The auctioneer would travel from bundle to bundle followed by company agents and they would bid on each pile,” says Smith. “Each sale took maybe a minute and at the end of the day farmers would tally their sales slips to learn how much they made that season. Now, they negotiate their contracts with the merchants ahead of the growing season and, except for a couple holdouts in Kentucky and elsewhere, the auction-houses have all vanished.”

Age of Regulation

“My father told stories about going to market in Petersburg and coming home with nothing, because the market was flooded with tobacco and no one was buying,” says Hart Hudson. In 1938, as a means of stabilizing tobacco prices and putting a stop to overproduction, the federal government passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act. The legislation assigned farms specific allotments of tobacco they could grow each year, thereby stabilizing supply, fixing prices and, barring catastrophic weather, guaranteeing farmers’ income. “The regulations gave you a certain amount you could grow,” says Hudson, “and guaranteed how much money you’d make when you sold it.”

Then came 1998’s landmark Master Settlement Agreement, wherein the four major U.S. tobacco companies agreed to settle Medicaid lawsuits brought by 46 states to help cover the costs of medical treatments patients incurred due to smoking. The agreement stipulated payment of $206 billion to states over 25 years, with subsequent yearly payments of as much as $10 billion per year in perpetuity—payments are calculated with offsets for inflation and production volumes as compared to 1997 stats, and so are subject to change. It also reigned in industry promotion practices—especially those targeting youths—and provided $5.5 billion in aid to vulnerable tobacco growers for a period of 10 years. It was the largest settlement in U.S. history, and sparked increased lobbying efforts on behalf of the companies. In 2004, those efforts led to the passage of the Fair and Equitable Tobacco Trade Reform Act (FETTRA), which marked the beginning of the tobacco market’s 10-year transition to a free market system.

Jay and April Jennings and their son Jackson in an irrigated tobacco greenhouse on their Chase City farm.

Photo by Tracey Lee

The passage of FETTRA fundamentally changed the face of tobacco farming in the U.S. For the first time in almost 70 years, farmers were forced to compete with one another as well as international growers for direct contracts with tobacco companies. To help ease the transition and offer small farmers a way out, a major component of FETTRA was the Tobacco Transition Payment Program, which was referred to by farmers as the “buyout.”

“Basically the companies wanted to deal with a few hundred bigger growers as opposed to thousands of smaller ones,” explains Scott County agricultural extension agent, Scott Jerrell. “So the federal government agreed to make $10 billion worth of payments over a 10-year period to small farmers who decided to give up tobacco farming, most of whom used the money to invest in livestock or vegetable production.” (Once farmers accepted the buyout, they would not be allowed to grow tobacco ever again.)

Meanwhile others—like Hart and Glenn Hudson—chose to stay in the business and invested in expanding their operations. They now lease or ownabout 8,000 acres, planting nearly 1,000 of those with tobacco each year. The process was made all the harder because it often entailed leasing or purchasing property from former area growers—in South Hill, there were around 35 farmers growing tobacco before the buyout. A little more than 10 years later, there are just three.

“It was a hard decision to make, and it was rough to see so many family farms go out of business, but this was our business and we decided to stick with it,” says an emotional Hart Hudson. “And ultimately we feel it was the right decision to make.”

Another farmer who chose to stick with it was Jay Jennings. After studying political science and earning a master’s degree in public administration from Virginia Tech, the 30-year-old decided to return home to the family’s Chase City farm. Along with his father Jim, 61, Jay continues his grandfather’s legacy by cultivating around 250 acres of flue-cured tobacco for their company, JF Leaf, LTD. “My grandad began raising tobacco in the 1960s on some of the same land we farm today,” says Jay. “We take pride in that legacy and plan on carrying on that tradition long into the future.”

While FETTRA put more than 75 percent of the state’s growers out of business—in 2000, there were 4,000, but by 2009 there were approximately 895—Virginia is growing almost as much tobacco now as before the buyout. In 2003, 23,000 acres were under cultivation—today, there are about 21,000.

“That catches people by surprise,” says Reed. “The total acreage is about the same as before, it’s just the farms have gotten larger. The ones that stayed in it have increased their size by two, three, four-fold.”

Though most of the tobacco grown in the Commonwealth is flue-cured and mainly used in cigarettes, two other types of tobacco are grown as well, though on a much smaller scale. In 2015, farmers grew 575,000 pounds of dark fire-cured tobacco, which is mostly used for pipes, chew and snuff, and 2.41 million pounds of burley tobacco, a lighter air-cured variety also used in cigarettes.

The Organic Alternative

On a Tuesday morning in Skipwith, a small Mecklenburg County community, around 50 vehicles—mostly farm trucks—pack the gravel parking lot of New Hope Church. Inside the meeting hall, about 75 farmers ranging from 25-45 years old interested in learning more about USDA certified organic tobacco farming are listening to presentations given by Virginia Tech and N.C. State agronomists. To be considered organic, growers must meet certification standards, which include the use of non-artificial fertilizers and pest-control agents, as well as certain land management practices (managing watersheds, for instance). With presenters constantly pausing to answer questions from the audience about proper nitrogen uptake in plants and how to calculate nutrient release over the growing cycle, the event has the excited, participation-driven feel of a specialized conference or lecture. For this new wave of farmers, none of whom have been in the tobacco business before or are positioned to compete in the large-scale market FETTRA created, organic tobacco seems to promise a way to diversify their livestock and/or produce operations while turning a profit.

A worker at JF Leaf Ltd. in Chase City carries moist baby tobacco plants ready for planting.

Photo by Tracey Lee

“Over the course of the last 6-8 years, as we’ve seen the rise of cigarette brands like Natural American Spirit,” which is produced by Santa Fe Natural Tobacco, a subsidiary of North Carolina-based R.J. Reynolds. “That demand has created a market for organically grown tobacco,” says Reed, who organized the event. “Because of the labor involved and the newness of the market, it’s not something you grow on a large-scale, but farmers are getting as much as double the price per pound compared to traditional tobacco, and that’s very attractive.” So attractive that, according to the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services spokeswoman, Dawn Eischen, in 2016, around 17 percent of the total volume of flue-cured tobacco grown in the Commonwealth was organic. At 8 million pounds, that made organic tobacco the state’s largest organic agricultural product. “We’ve seen increases in production for six years straight, but are slated to reduce by just a bit this year,” says Reed. “There’s a lot of debate about world-wide demand and that’s creating some uncertainty .… It’s a young niche, and so we’ll just have to wait and see what happens. But overall I think the future looks pretty promising.”

Joe Camel and Marlboro Man billboards have been replaced with advertisements warning of the dangers of tobacco use, and smoking in public spaces in Virginia has been banned for nearly a decade, but for Virginia farmers, manufacturers and leaf merchants, tobacco is still big business.

And there’s a reason: What France is to Champagne, Virginia is to tobacco. It’s the gold standard.

“Our biggest competitors are Brazil, China and Zimbabwe,” says Reed. But while the competition seeks to imitate, there remains a discernable difference in the product. “Their climate and soil conditions can’t replicate ours, they don’t uphold the same quality controls or environmental standards, their labor force isn’t as educated and they don’t have the research or experience we have,” he adds. “The taste and quality of Virginia tobacco is simply the best in the world, bar none.”

“Here we are 400 years later and that’s still the case,” says Glenn Hudson. “This family is proud to be carrying that lineage into the future.” SouthHillVa.org, Ext.VT.edu, Altria.com

The Cure

Methods for curing tobacco may have modernized over the years, but family recipes remain fiercely guarded. Click here to read more.

Barn Saving

The Tobacco Barn Preservation Project honors a way of life that has all but disappeared. Click here to read more about the organization’s efforts and successes.

Pride of Place

The Tobacco Farm Life Museum celebrates a partnership between South Hill’s Community Development Association and area tobacco farmers. Click here to read more.

This article originally appeared in our June 2017 issue.