Legendary Look magazine photographer Robert Lerner on the golden age of photojournalism.

“Fancy Free,” Lerner’s signature photograph, 1952.

Robert Lerner in Richmond, 2014.

Jimmy Durante with dancer, 1968.

Robert Kennedy with miners, 1960.

Exhausted Haitian woman in market.

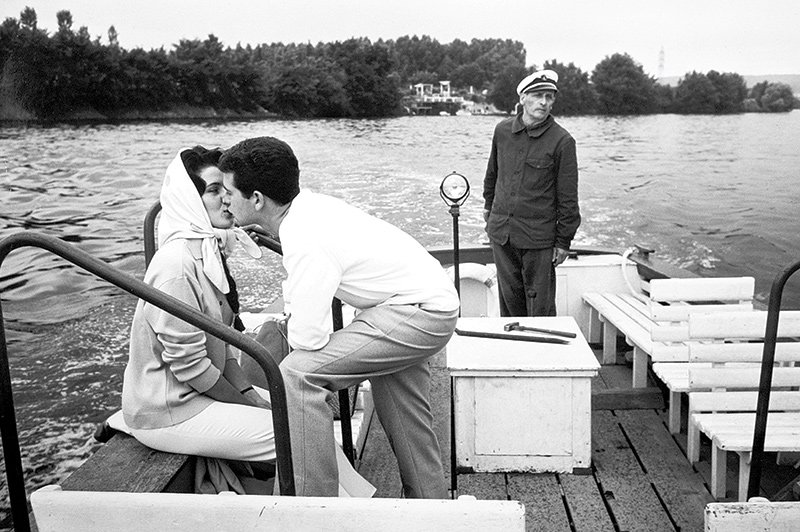

An engaged couple in Paris, 1960.

A guard dog in a New York Macy’s department store, 1958.

Former president of Haiti Papa Doc Duvalier, 1962.

Vietnam War protest in Washington, D.C., 1972.

Queen Elizabeth II, 1970.

Paris street scene, 1949.

“It is the incredible power of a photograph that transports me to an intimate recollection of that moment,” says 89-year-old photographer Robert Lerner.

A photojournalist for Look magazine from 1951 to 1971, Lerner photographed cultural and political icons from Queen Elizabeth II and former president Richard Nixon to poet Robert Frost, comedian Jimmy Durante and Haiti’s former president Papa Doc Duvalier, and produced 10 cover shots for the popular large-format lifestyle glossy.

Lerner also covered the medical and religion beats, among others, winning awards from the Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge, the American Institute of Graphic Artists and the Urban League. His work is preserved in the Look Magazine Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress, and his photo “Textures,” shot for a story about criminal housing neglect in parts of Chicago, is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Dmitri Collection comprising the best photographs of the 1950s.

In 2003, the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk presented the first retrospective of Lerner’s work in a five-gallery, nine-month show featuring more than 135 of his photographs.

Today, the Yorktown resident since 1999 and native of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is working on a memoir, teaching his craft and lecturing.

“You learn by seeing what the good guys and gals are doing,” says Lerner, noting that famed French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, an early influence, took the ordinary and made it extraordinary. “The passion is always somewhere in your psyche,” he explains. “Wherever you look you’re putting a frame around it.”

Life photographer Frank Scherschel taught me the basics in film in ways that you would never get in school because of the depth of his experience and the people he knew. He would arrange for me to hang around the Milwaukee Journal, which had a great photo staff.

When I worked for former Chicago Tribune photographer Fran Byrne, we would do a portrait in the morning, shoot glassware in the afternoon and a wedding the next day. I was one of a handful of photographers who never specialized, because I grew up with a mentor who never specialized.

My wife Dainie was a talented girl with a tremendous personality. She knew more about my dream than anybody in the family. We raised four children, twins David and Irene, Sally and Laura. When I suggested living in Paris for a year, she said, ‘I’m packing my bag.’ We were there from 1949 to 1950 and fell in love with it. One picture that stands out from that year’s work was an image of the Eiffel Tower. I discovered that Hitler visited that exact spot a few years earlier, strutting along when Paris fell.

When I returned home, I showed my portfolio of work to Ben Wickersham, editor of Look magazine’s Chicago bureau. He asked questions, looking to see if I was inventive. He was one of the most important persons for my career.

My signature photograph “Fancy Free” has had a life of its own, published many times. The superb dancers were positioned on top of a flight of steps with Chicago’s skyline behind them. The woman wore a flowing costume while her husband, in contrast, wore a sailor suit. Each artist will be represented in his biography by one piece of work—there’s always one picture that identifies you and it’s only one.

I had a habit of working closely with writers. I coordinated interviews in a location advantageous for photographs. Together, we would get emotional responses I would never get any other way.

Girl with ball in Paris, 1940.

Kids, 1950.

Casey Stengel and Mickey Mantle, 1950.

Caracas cemetery, 1960.

Bette Davis on a rowboat in a pool, 1960.

Woman with red sari in the river, India, 1960.

Liz Montgomery, 1960.

Leo Nomellini (number 73) or the San Francisco 49ers, 1960.

Lulu and Mama Cass, 1970.

Women praying at the Shrine of Guadeloupe in Mexico, 1970.

The Wailing Wall, Jerusalem, 1980.

Peruvian boy, 1960.

Indian women going to market.

Unitarian family in church.

Walt Disney was playing the upright piano and showing Dick Van Dyke the music when I accompanied the young actor to meet with him for his upcoming role in Mary Poppins. Those pictures were never used. The Look story was canceled by an overcommitted Van Dyke.

Actor Donald Sutherland, sporting long hair and a beard, had the idea to jog in a field. Sometimes the subject has better ideas than I do. I shot actress Bette Davis in a dory in her Beverly Hills swimming pool with her adopted son. People say, ‘You photographed Bette Davis.’ I say, ‘Yeah, but I photographed Russell Hicks.’ Nobody knows who he is—a coal miner living near Bluefield, West Virginia. He did all sorts of things and never had a dime. He was not going to give up.

I photographed a lone man at Jerusalem’s Western Wall and captured a shot I did not appreciate right away. This kind of image-making is so curious in so many ways. The photograph showed a man who represented Israel—one small, Orthodox Jewish man praying, surrounded by people who didn’t want him there.

I photographed presidential candidates Adlai Stevenson, John F. Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy. The Kennedy pictures are in the John F. Kennedy Library and the Robert Kennedy Center. Once, when I deplaned in a small Bluefield, Virginia, airport a guy at the bottom of the ramp asked, ‘Are you Lerner from Look?’ It was Jack Kennedy making sure I had a ride.

I won top prizes with TWA for their annual report from the American Institute of Graphic Artists. For their report, I lay down on the runway at Miami International Airport with an 8mm fisheye lens. FAA people watched over me while I shot images of planes flying overhead. Photographers need to be risk takers. Without it, you are paralyzed. I freelanced with the New York Construction Association, Phillip Morris, Great Northern Paper, the New York University School of Dramatic Arts and IBM. Between Look and my freelancing I was in 50 countries.

When I wasn’t on assignment, I did what I call “wanderings,” photos I took as I wandered around a location shooting what captured my attention. I still do this.

It was the greatest gift to know that I would show people an honest and straightforward, but fresh look at what was happening. Looking back, it was the only thing that I could’ve ever done with my life that would’ve meant anything to me.

To see Lerner’s work at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, go to Chrysler.org

This article originally appeared in our June 2016 issue.