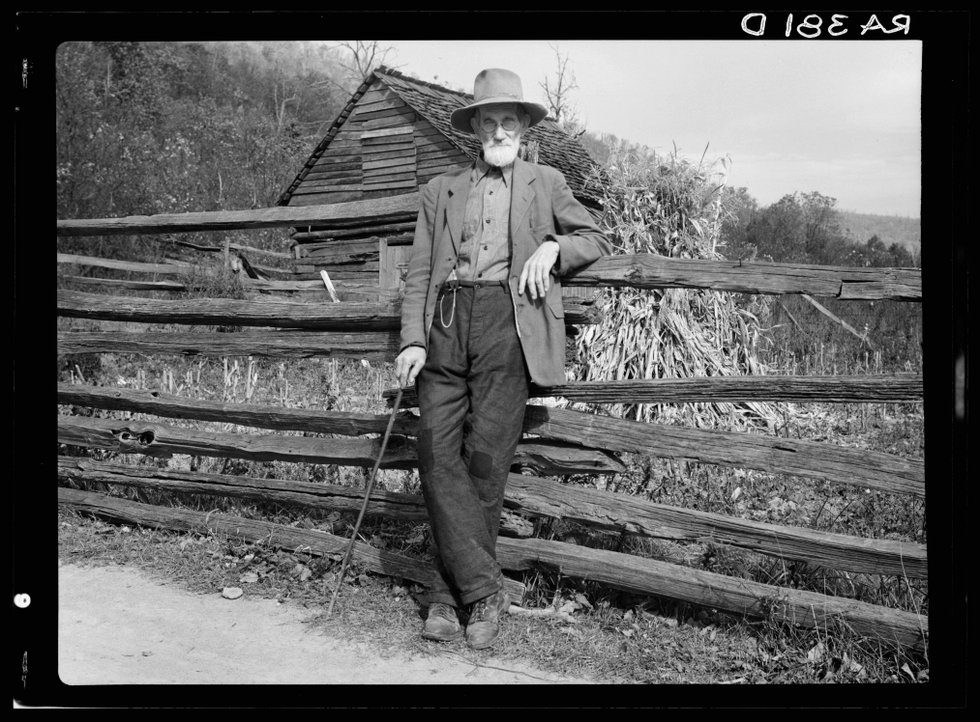

A Depression-era travel guide reveals a hidden Virginia.

AGC/8b26000/8b266008b26680a.tif

Imagine you want to drive from Richmond to Harrisonburg. But it’s 1940 so, instead of Google Maps, you turn to Virginia, a Guide to the Old Dominion, a hardcover book, newly published under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Deep within its 710 pages, you’ll find a 144-mile itinerary that sets out from the state capitol on Jefferson Highway, “asphalt paved throughout” and passes through Louisa, a settlement, we’re told, known for the “worst lodging in all America,” according to a warning heeded by the Marquis de Chastellux, an 18th-century French military officer.

By mile 104.9, you’ve reached the banks of the Shenandoah River where, in 1716, Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood buried a bottle with a note claiming the land for King George I. He marked this achievement with what sounds like an epic bender of Champagne, Burgundy, claret, Irish whiskey, brandy, rum, and cider.

Then comes Keezletown which, the guide notes, might have been the Rockingham County seat if only it hadn’t lost that honor to Harrisonburg in a horse race. Intrigued, you continue on toward West Virginia, but this long strange trip ends abruptly at the state line.

Dip into this Federal Writers’ Project book and you’ll find 24 more driving routes, all with mile-by-mile narration. Part of the American Guide Series, it was created by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the same New Deal agency that funded the Blue Ridge Parkway, the Norfolk Botanical Garden, and thousands of other Depression-era projects.

Critics initially denounced the guidebooks as a boondoggle, according to Scott Borchert, author of Republic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover America (Macmillan, 2021). “But the books surprised everyone with their style and verve,” he notes. “They have this kind of literary quality to them, a craftsmanship that’s unexpected.”

Top-notch writers helped. John Cheever, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Studs Terkel, Saul Bellow, and Zora Neale Hurston are among WPA guide contributors who went on to literary fame. The rest were the unemployed librarians, academics, and journalists felled by the Great Depression. All had declared insolvency, but their work has inspired travelers for generations.

“Hats off to those writers, researchers, and editors,” says Gerald Howard, the retired executive editor of Doubleday publishing. Howard used the volume on a 1970s bike trip through the Shenandoah Valley. “The depth of folklore and historical background in the book really deepened the touring experience. They took what they were doing seriously.”

No breezy read, the guide slogs through crop yields and geologic formations, before tossing in a surprising reference to the apparently tasty dish of opossum garnished with sweet potatoes.

“The book’s like a fruit cake that has some great nuggets in it and long stretches where it’s pretty dry,” says David A. Taylor, a Washington, D.C.-based writer who is developing a podcast about the Federal Writers’ Project called The People’s Recorder.

For the Virginia book alone, which is encyclopedic in scope, the staff interviewed around 1,400 people, Taylor says. “They were looking to be led by a local sense of history and stories.”

Along with the travel guide, the Commonwealth also published a second book, The Negro in Virginia in 1940. Based on interviews with former slaves and their descendants, it went on to become a national bestseller and Book of the Month Club selection.

True to the era, the guidebook consistently refers to “The War Between the States” but those who persevere will find vivid historical tidbits like George Washington’s unfortunate stay in a tavern as he passed through Fairfield, near Lexington. When rain poured through the roof that night, it ruined a painting that the future President had just purchased.

And then there’s the town of Christchurch, where a 1711 endowment funded quarterly sermons against the “four reigning vices:” atheism, swearing, fornication, and drunkenness, all of which suggests that this tiny Middlesex County crossroads may have been the Las Vegas of Colonial Virginia.

Above all, the book celebrates the Old Dominion. In her introduction, Eudora Ramsay Richardson, who supervised the project, rolls out the red carpet, enticing visitors to sample the state’s “spoonbread, Smithfield ham, Brunswick stew, peanuts, and tobacco.” The guide, she promises, chronicles the exploits of the famous and nearly forgotten. And the state, she makes clear, is a place eager to share its past. “We welcome the traveler to our shrines.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue.