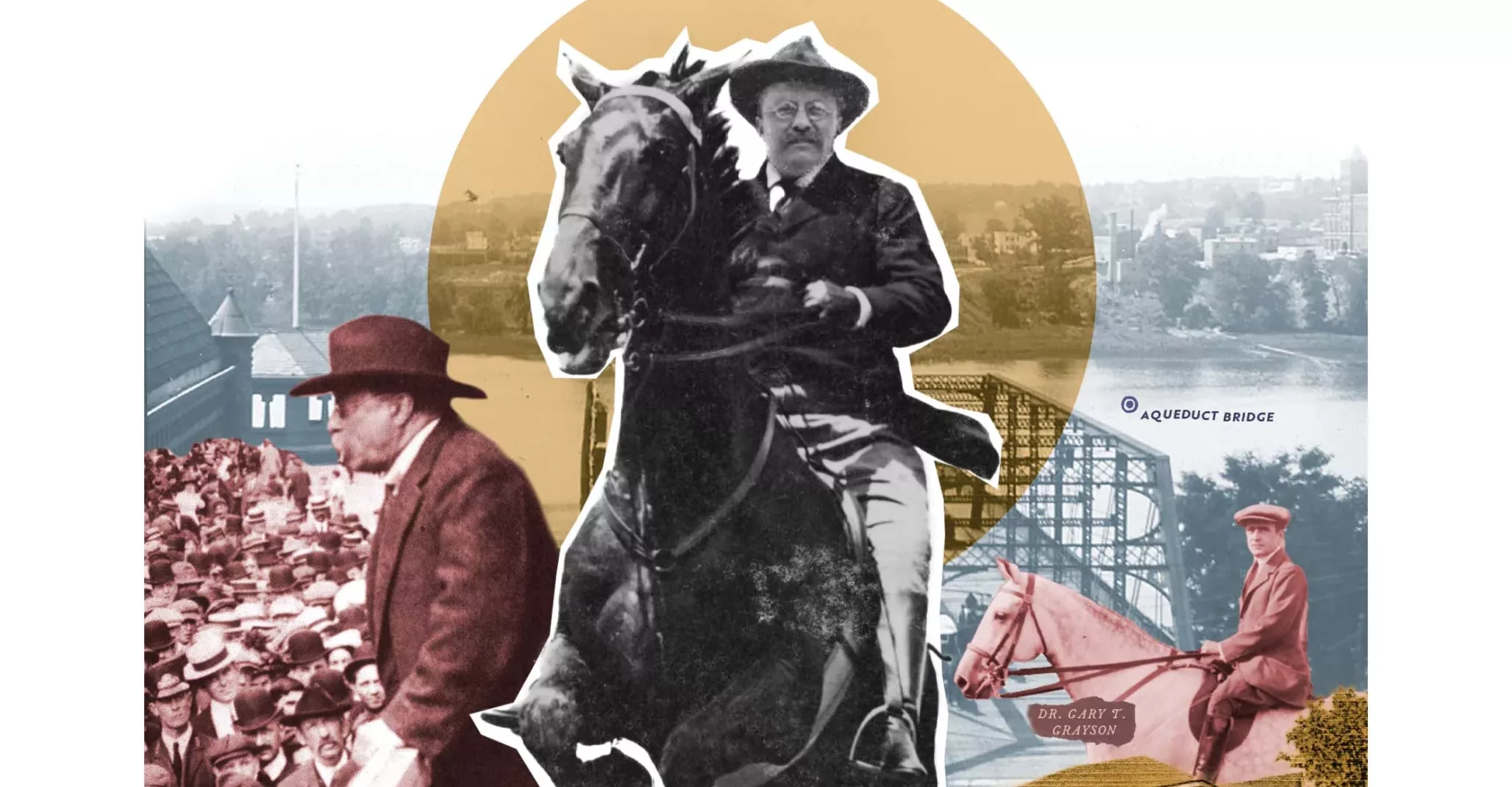

It was a cold, overcast day in mid-January, 1909. Theodore Roosevelt, known as Teddy or T.R., 26th president of the United States, was holed up at the White House. The trust-buster, Rough Rider, and hero of San Juan Hill with his horse, Texas, had a keen interest in staying fit.

e’d hiked the Alps with his family, bought land in North Dakota to raise cattle, boxed, embraced jujitsu, and all-around championed the “strenuous life.” It was imperative, he decided, that each officer in the Army pass a physical fitness test to qualify for promotion.

Roosevelt had become increasingly concerned after observing the young officers from the war college classes who joined him for fast-paced hikes, cliff climbing, and fording deep creeks in Rock Creek Park. He complained that some were utterly worthless physically. And he was highly doubtful of their performance in combat.

Their ineptitude shocked him. At one post, a cavalry colonel couldn’t keep his horse “at a smart trot” for half a mile. Another officer, a major general, was afraid to let his horse canter. Some were totally sedentary.

Time was short: T.R. had just over a month left in office. William Howard Taft would succeed him as president on March 9. If he planned to make reforms, he had to act fast.

After meeting with the Army Chief of Staff and the Commander of the Department of the East, they charged each officer with walking 50 miles or riding or bicycling 100 miles within three consecutive days. “Something many a healthy middle-aged woman could do,” T.R. challenged, sure that the test would “force every officer into frequent daily exercise, especially middle-aged ones, so they’re always fit for any contingency.”

The press called it “capricious tyranny,” and many aging, desk-bound officers conspired with congressmen to cancel it. Their efforts didn’t work.

Roosevelt asked Navy Surgeon General Admiral Presley M. Rixey if the Navy should have the same test. Rixey wanted to try it first, riding 100 miles in a day. Rixey and Roosevelt rode and hunted together frequently in Virginia.

Instead, 50-year-old Roosevelt decided that he and his military aide, 44-year-old Major Archibald “Archie” Butt, would ride 104 miles to Warrenton and back to D.C. with 56-year-old Rixey and 44-year-old Gary T. Grayson, his naval physician.

On Jan. 13, 1909, the band of four set out. The forecast cautioned hazardous conditions—a

low-pressure center had enveloped southern Virginia. The morning temperature didn’t get above 30°F, evening temps would plummet to 5°F, and rain would turn to snow.

After steak and coffee, Rixey evaluated Roosevelt’s heart. Deemed fit for the ride ahead, T.R. and his posse left for Warrenton well before dawn—at 3:40 a.m. The journey is 58 miles by today’s roads. The men changed horses at Fairfax Court House, Centreville, Cub Run, Buckland, and Warrenton, arriving at 11 a.m. at the Warren Green Hotel to more than a thousand cheering people.

Roosevelt’s stop-over was barely an hour. He spoke briefly, met leaders, inhaled hot soup and tea, and departed just past noon. They stopped at the same stations for the same cavalry mounts, riding 8 hours over frozen, rough roads. The horses were not happy.

Butt’s horse fought the bit the entire way. Grayson’s horse reared and kicked and nearly hit him when he dismounted to check that the President’s saddle was secure. He remounted 15 minutes later.

It was January, after all, and after 5 p.m. Passing through Centreville, it became pitch-black. A gale-force sleet storm drove into their faces covering Roosevelt’s glasses and coating the roads. Snow matted their clothing.

It was now night, and nearing the end of their journey—at the Aqueduct Bridge across the icy Potomac—Roosevelt refused a carriage. He led his group over the bridge and traversed Pennsylvania Avenue, treacherous and snow-covered, arriving at the White House that evening at 8:30.

Mrs. Roosevelt—Edith—met the men with mint juleps. “Dear, I apologize for arriving late for dinner,” was T.R.’s reported greeting. The exerciser-in-chief had proved his point. And then some.

This article originally appeared in the December 2024 issue.