A new series explores the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Virginia with first guest blogger S. Waite Rawls III, President and CEO of the Museum of the Confederacy.

The 1860 Presidential Election

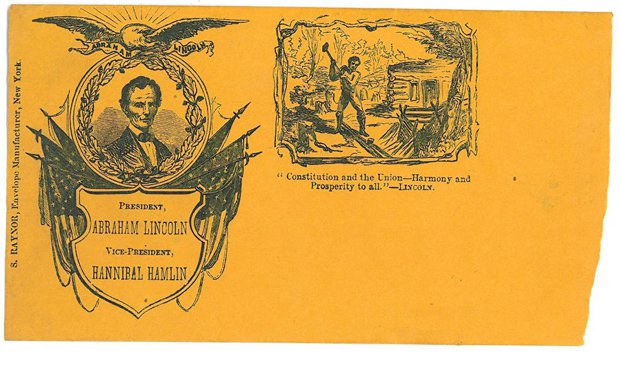

Artwork depicts the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln.

The 1860 Presidential Election

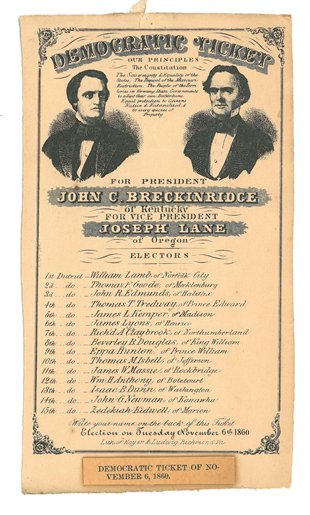

The 1860 electoral ballot for Vice President John C. Breckinridge.

Whatever we think of politics and politicians today, it doesn’t hold a candle to the Virginians of 1860. The two major political parties of the antebellum era—Democrats and Whigs—had broken completely down as the sectional strife over economics, slavery, and the westward expansion led to multiple new factions.

The Democrats split apart at their convention with Northern Democrats nominating Stephen A. Douglas, the man from Illinois who had defeated Abraham Lincoln in the 1858 race for U. S. Senate. But because Douglas’s definition of “state sovereignty” in the new territories limited the expansion of slavery, the hard core faction from the Deep South split off and nominated Kentuckian and U.S. Vice President John C. Breckinridge. The Republican Party was brand new and represented almost entirely a sectional party of New England and the Midwest. By Republican standards, its candidate, Abe Lincoln, was a moderate.

Tempers were so frayed by those partisans, and most Virginians were so put off by the bitter sectionalism, that a new party was created—the Constitutional Union Party—and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. The platform was two paragraphs long as the party was willing to do anything to compromise the extremists and save the Union.

The election promised bitter results. A year earlier, then Virginia Governor Henry Wise, a Breckinridge man, had begun stockpiling weapons in anticipation of the election. Elected in 1859, Virginia Governor John Letcher, a Douglas man, called out the militia on Election Day so that any riots could quickly be quelled.

John Bell got 44% of Virginian’s votes to beat John Breckinridge by 156 votes of the 170,000 cast. Stephen Douglas got 16% of the votes, and almost nobody showed up to vote for Abraham Lincoln, who received about half as many Virginia votes as Ralph Nader did in 2008. Lincoln ended up with less than 40% of the national votes but won the election by sweeping all of the electoral votes from the North.

The election of anyone from the sectional Republican Party, even the moderate Lincoln, led to the secession of the Deep South states; but there were no riots in Virginia. Virginians hoped that they could craft compromises that could preserve the Union. They did have a Secession Convention, which should have been named the “Save the Union Convention,” because the major topic of concern was what Virginia—the mother of states and statesmen—could do to save the Union that Virginians had built. Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Harrison, Tyler and Taylor—all Virginians and U. S. Presidents—were Virginia’s role models, not the extremists of Massachusetts or South Carolina.

By 1861, John Tyler was the only survivor of that group, and he chaired the “Peace Convention” that attempted to persuade Lincoln that the best way to save the Union was not to start a war. But Lincoln refused to meet with Tyler’s group, and his call for troops from Virginia in the aftermath of Fort Sumter was the proximate cause of Virginia’s final decision to secede. Once Virginia’s die was cast, its strong Unionists fell in line with their State. Even John Tyler cast his lot with Virginia and served as a member of the Confederate Congress until his death in 1862.