A hero’s quest, a love story, and the story of a young artist coming of age.

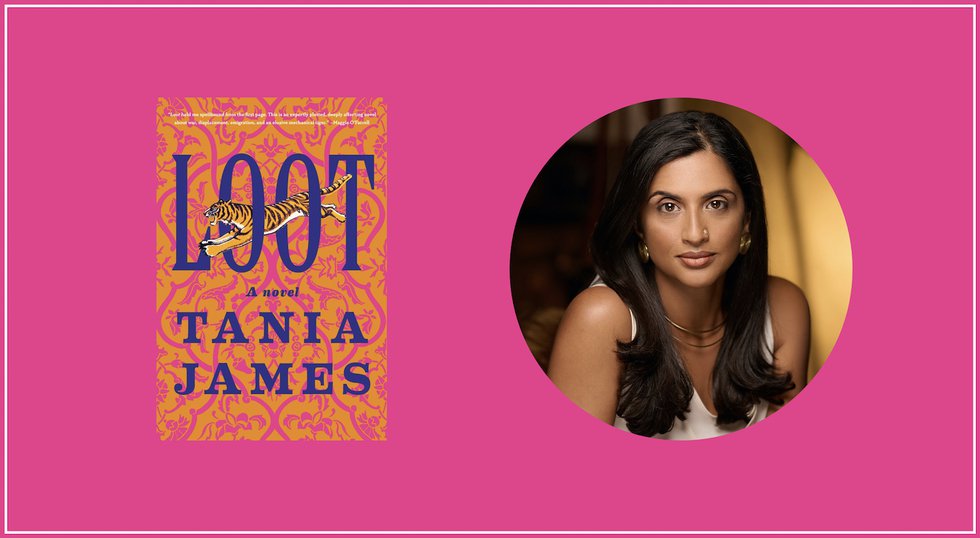

(Headshot by Elliott O’Donovan)

Loot by Tania James. Knopf. pp.304. $28.

Konstantin Rega: What got you into writing?

Tania James: I think I was always writing. But one of the pivotal moments was in high school, where I got to participate in the Governor’s School for the Arts in Kentucky. It was like an arts boot camp for young people.

Before, I’d thought of writers as being mostly dead, mostly white. Because that’s the people who I was reading. But my teachers there were two black poets, and just being in their presence opened up the possibility that I could do this too, that there was no room for more than one kind of writer.

If you were telling someone about Loot, what would you say?

Well, I started this novel before the pandemic, and I’ve never had more fun with a novel than with this one—even though it’s about some weighty subjects. So I hope it’s balanced by the humor, the adventure, and the irreverence of the story itself.

Originally, I conceived of this as a heist novel. I thought it would take place in an English country house, and it would be about two people who are trying to take back this work of art. Then I thought about the artist who’d made it and what it meant to him. This also allowed me to wonder about the restitution of plundered artifacts and the idea of to whom a prize of war belongs to.

It’s a novel that’s doing a lot of different things. But I really want the reader to get a sense of delight and adventure, too.

This is your fourth novel, is this a departure from your usual work?

It does feel like a big departure. I’d never written historical fiction before. I’ve never devoted so much time to learning so many different fields, like woodworking, English country house culture, or seafaring in the early 1800s.

But I did return to questions that have appeared in my other books, about authorship and identity. And, in this case, sovereignty and what a work of art means to the person who’s making it. It’s not always an intentional act for me.

With every book I’ve written, I’m entering into territory that I’m familiar with, but they still feel very different, too. With this one, I was interested in tracing the various paths that people took because of a particular kind of catastrophic time.

Not being used to historical fiction, how did you adjust?

I had a hard time with the research in the beginning because I couldn’t find a whole lot about Tipu’s Tiger. And far less about the people who made it. All I could find was that it was probably a collaboration between the Sultan’s clockmaker and some local artisans.

At first, I felt a little bit paralyzed by that lack of information. But then I decided that perhaps the lack of information liberated me from being overly faithful to history—which can also be a crippling problem when you’re writing historical fiction. You can sort of feel loyal to all that you’ve learned. So I did a lot of foundational research to get a sense of the way people talk to each other, and I paid a lot of attention to details that would matter to the characters.

Is that something you enjoy about being a writer?

If you’re a curious person, being a writer gives you the opportunity to exercise that muscle on a fairly daily basis. And I love those fleeting moments when I forget myself in the writing process. I’m just kind of locked into the world in a different way, that allows me to forget my own ego which is very liberating.

And is there anything else brewing?

I’m trying to get back into that space, carefully wading into those waters. Before I wrote this novel, I’d written some drafts for a few other ones. And there is one thing I feel I might go back to, that might be calling to me. I still consider myself a student of writing as much as I am a writer. I always feel like I have so much still to learn, which is an exciting place to be.

Get a copy at The Bookstore.