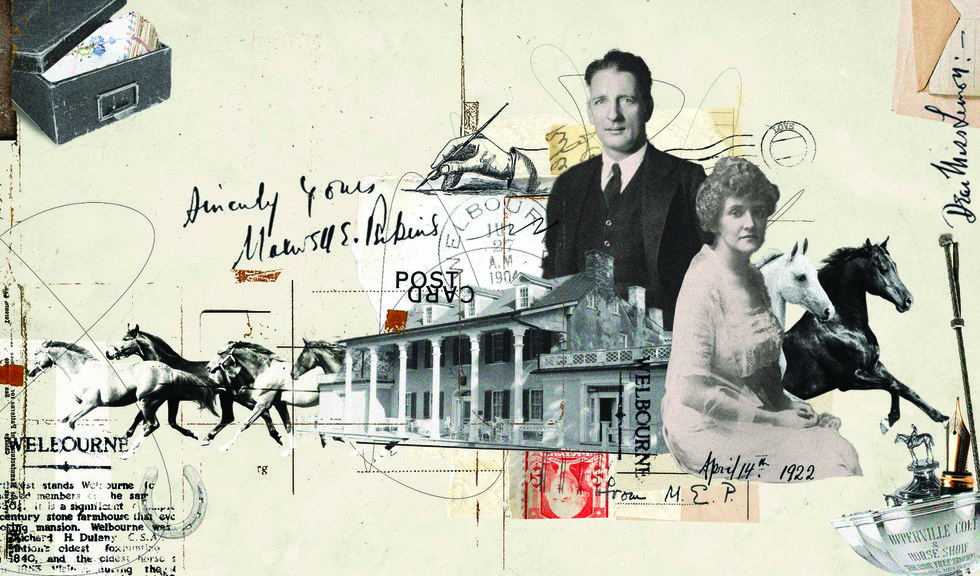

For 25 years, Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins sent them to Welbourne, a Middleburg estate.

At the epicenter of hunt country, Welbourne holds stories of horses, royals, and a secret literary romance. Built in 1750, the Middleburg estate became the home to Colonel Richard Henry Dulany, who fought in the Battle of Gettysburg. A passionate horseman, Dulany founded the country’s oldest hunt club, The Piedmont Fox Hounds, in 1840.

Even today, the hounds form a swirl of black, brown, and white on the lawn of the estate before the master of the hunt sounds the call. Horses and hounds then race through the fields, over fences, and across dirt roads, as they did when the Colonel’s ancestor, Daniel Dulany, Jr., hunted with George Washington.

The Colonel also founded the Upperville Colt & Horse Show in 1853. “Before the first Upperville Horse Show, he traveled to Manhattan to consult with Louis Comfort Tiffany about a suitable trophy,” says Dulany’s great-great-great granddaughter, Rebecca Dulany Morison Schaefer, who is the innkeeper at Welbourne. “Tiffany saw that this kind of sporting event could be a lucrative market for his business, and donated the cost of his craftsmanship for the silver cup.”

One hundred and seventy years later, Upperville’s horse show is the oldest and perhaps most prestigious in the country, with over 2,000 combinations of horses and riders competing in events based on international standards.

The Belle of Hunt Country

As proprietor of Welbourne, a bed and breakfast since the 1930s, Rebecca Schaefer keeps eight generations of her family’s stories alive. She recalls her great aunt, Elizabeth Lemmon, who kindly indulged young visitors, whipping up milkshakes for her as a child. A Baltimore debutante, Lemmon took up residence on the estate in 1915, after the death of her father, and lived on the property at Church House until three years before her death in 1994 at age 100.

The “belle of the hunt country,” Lemmon taught singing and dancing at Foxcroft School and raised champion boxer dogs. “My dogs are raised like you wish your children were,” her letterhead read. A fan of both opera and baseball, she managed Upperville’s semi-pro baseball team and refused to answer the phone during the Metropolitan Opera’s Sunday afternoon radio broadcasts. Both forward-thinking and traditional, she read astrological charts and loved to knit.

Lemmon was 28 in 1922 when she met Maxwell Perkins in Plainfield, New Jersey, when she was visiting her aunt. The esteemed editor, 38 at the time, was nurturing the talents of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, among others. He and his wife, Louise Saunders, a friend of Lemmon’s, had five daughters, but their relationship was often strained. Lemmon paid a visit to Louise in Plainfield and, from the moment he saw her, Max Perkins was captivated. Even Louise felt the electricity between them.

A Passionate Affair By Mail

Not long after, Perkins wrote his first letter to Lemmon from his office at Charles Scribner’s in New York. “I always greatly liked the phrase dea incessant patuit, [and the goddess was revealed by her step],” he told her. “But I never really knew its meaning until I saw you coming through our hall the other night.”

“Their worlds could not have been farther apart,” Rodger Tarr writes in the introduction to his book, As Ever Yours: The Letters of Max Perkins and Elizabeth Lemmon, (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), “yet they quickly became friends.”

Lemmon wrote back, launching an intimate correspondence that would endure over the next 25 years, ending only with Perkins’ death, at 62, in 1947. In Lemmon’s 1994 obituary, a grandniece describes the relationship as “a passionate affair by mail.”

“You will surely come over sometime,” Perkins wrote two years into their correspondence, on Oct. 7, 1924. “Won’t you tell me when you do? At least if you will let me see you. Not otherwise. You know it is only of such will as I have that I got out of Virginia without seeing you.”

In his letters, Tarr observes in his book, Perkins describes the burdens of his rising star status at Scribner’s, which came with an ever-increasing workload. “His genius,” Tarr adds, “was finding genius and cultivating it.” Perkins chafed at the role of public figure. But his own fame was increasing almost as rapidly as that of his authors.

Visiting Authors

In letters published in As Ever Yours, Perkins describes fishing in Key West with Ernest Hemingway. “I hold the world’s record for the Giant King fish,” he tells Lemmon. “If you’d seen me with a grizzled beard looking as tough as a pirate you could imagine me doing nothing else unless it was murder.”

Of Thomas Wolfe, who responded to the editor’s cuts with even more pages, he confided to Lemmon, “God knows what the result will be, but I suspect it will be the death of me.” He also wrote intimately of family life. Whatever the topic, Tarr notes, Perkins often added, “I am telling this only to you.”

It’s not clear when, but Perkins did visit Welbourne once, and in 1934, asked Lemmon to host both F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe on separate occasions. Both authors wrote thinly veiled stories based on Welbourne, which Fitzgerald placed in the fictitious town of “Warrenberg.”

Wolfe described Welbourne as, “one of the most beautiful plantation houses you ever saw. The house in its general design is not unlike Mount Vernon,” he wrote in a letter to his mother, “yet surpasses it in its warmth and naturalness.”

Fitzgerald, Lemmon would later complain, was often drunk and “showing off.” When his story appeared in a November 1934 edition of The Saturday Evening Post, Tarr notes, she took offense that he had based his main character on her.

Ours Was a Secret Love

Long after Perkins’ death, when biographer A. Scott Berg interviewed Lemmon for his book Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, in 1978, she produced a shoebox filled with letters. “These are Max’s letters to me,” she told him. “I was Max’s confidante. Ours was a secret love.”

Secret, perhaps, but Perkins’ wife, Louise, knew of the ongoing friendship, and once asked Lemmon to look after her husband if something should happen to her. But the letters came as a surprise to Perkins’ oldest daughter, Bertha Saunders Perkins Frothingham, who remarked, “I’m so glad Daddy had someone to talk to.”

How many times did they meet in person? “No one knows,” Tarr says. But it’s clear they did meet, perhaps for several dinners, over the course of their 25-year friendship. Still, Lemmon insisted the relationship was platonic. “I never slept with Max!” she told Berg. “I never kissed him.”

By the late 1930s, a besotted Perkins confessed to Lemmon. “I wish I could talk to you, but .… I’m so happy to be with you that I can’t say anything.” But by 1940, he had fallen into despair, telling her, “I don’t think I shall ever see you again. But I remember everything about every time I ever did see you & there was mighty little in life to compare any of it to. I’ve always thought of you & all the time.”

They met for the last time at the Ritz Bar in New York in 1943. There, Tarr writes, Perkins reportedly attempted to profess his love in person. Instead, all he could manage was, “Oh Elizabeth .… it’s hopeless.” Later, Berg would describe the relationship as “a great 19th-century romance, and a totally platonic affair.” Lemmon never married.

If Welbourne’s walls could talk, they’d have more stories to tell. It remains a comfortable inn and is also a sanctuary for retired horses. With its gracious host, Rebecca Dulany Morison Schaefer, this historic estate welcomes guests into an engaging step back in time. WelbourneInn.com

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue.