VCU’s Richard Roth is a teacher, author, designer, collector and post-modern painter. Did we miss anything? Yes—and he doesn’t take himself too seriously.

The artist in Venice.

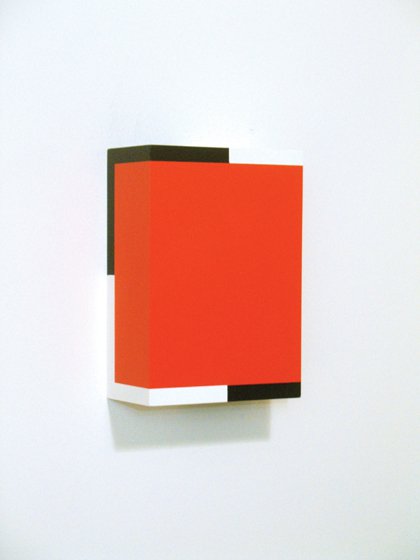

As Is (2011), acrylic on wood support (birch plywood).

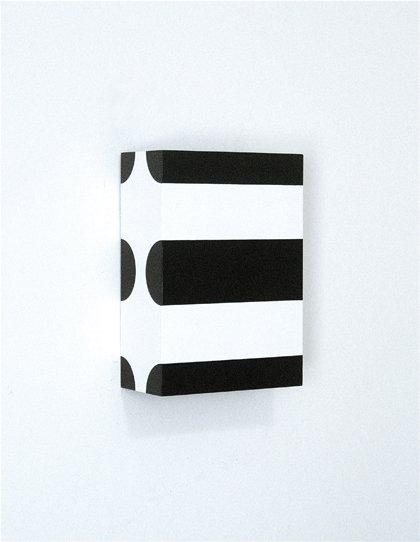

Toot Sweet (2011), acrylic on wood support (birch plywood).

When Richard Roth was hired to head up the department of painting and printmaking at VCUarts in 1999, he hadn’t picked up a paintbrush in four years. A minimalist working at the limits of painterly reduction, Roth had hit the wall, taking minimalism as far as it could go, and had stopped painting altogether. But Roth’s stature as an artist trumped any concerns about such an unorthodox move. His longtime colleague, Joseph Seipel, who was recently appointed dean of VCUarts, says of Roth: “Richard is truly a renaissance man, a triple threat. He is a brilliant teacher, a recognized author and a widely exhibited painter and designer. He is equally comfortable discussing philosophy and aesthetics as he is examining contemporary culture.”

When he was hired, Roth had been focusing on assembling various collections of everyday items (color charts, legal forms, ladies’ compacts, newspaper clippings). According to Roth, collecting was already in his DNA: “Artists are collectors by nature and by necessity,” he says. “We collect artifacts, vistas, animals, or people that serve as models or subject matter. From found objects to other art works, artists also collect for inspiration. The qualities of things teach lessons and nourish us. So many studios serve as private museums, chapels of ephemera and oddities to sustain the Muse.”

Prior to renouncing painting, Roth had been creating mini-installations composed of his highly reductive paintings paired with found objects. It was while sourcing the latter that he’d discovered a rich world of objects and all that is entailed in their acquisition. While painting felt stale, the world of objects was inspiring. Collecting things was a way of engaging with the world in unexpected ways. Roth’s collecting took him places he never would have gone otherwise, such as gun stores and make-up counters, forcing encounters with people he never would have met.

While he was drawn to certain items for purely aesthetic reasons, some, like the newspaper clippings of people grieving, were chosen because Roth was struck by how they provide the most profound example of the depth of human emotion. For the compact collecting, Roth admits wryly that he relied primarily on his wife to purchase them, “five or six at a time,” though he would occasionally buy one himself. He collects modern day examples—drawn to the make-up itself as opposed to the case—and thus displays them open. Unlike paint, the rouge and powder in compacts retain their richness even when left open. Roth is also drawn to the whole symbolism behind compacts and their connection to portraiture, how a woman takes brush and pigment and “paints” herself.

Roth’s interest in objects stems from his abiding belief in the democracy of aesthetics—how something ordinary, a piece of industrial design for example, can have the same visual merit as a piece of fine art. Though Roth started the collections as a personal venture with no real vision for what he’d do with them, he viewed them and the process of collecting itself as art. His “Modern Vernacular” collections have been shown at venues both in this country and abroad.

Roth assumed he’d made the complete transformation into a conceptual artist and would never return to painting. But six years ago, filled with trepidation, he got a studio. He likens the experience to remarrying one’s ex-wife: “You’re re-engaging with something so familiar, but your relationship to it has changed, and so it’s kind of scary.”

One notable aspect of the post-collecting paintings he has since created is their shape. Roth added edges all the way around, making them into box-like objects, extending out from the wall. He likes his paintings to “do more than one thing” and be looked at in more than one way. This new design created additional surfaces, and the painting gained a profile. “The three-dimensionality saved me,” says Roth. “It brought in an ‘objecty’ quality that tied them more to the world of objects as opposed to this elevated precious world of paintings.” It also meant that Roth no longer needed the found objects as addenda to his paintings and could now focus solely on painting, resulting in stronger self-contained work.

Roth’s sleek little paintings are deceptively simple. Typically, they are pared down to two or three striking hues and crisp geometric forms manipulated to create arresting optical effects. In some, the forms assume a prominent role, filling up the picture plane and spilling over onto the sides; in others it’s more about color. Though appealing eye candy, the paintings also represent a deep exploration into art, aesthetics and object.

Roth used to consider himself a modernist painter with all the gravitas that entails; now he sees himself as a post-modernist. The time he spent away from the studio, immersed in the world of objects, has caused him to lighten up and not take himself or his art as seriously. He signals this new attitude to the viewer through the use of titles: The barebones “untitled” or numbers of his early work have been replaced by verbal titles that add flavor and are sometimes even quite droll.

Since 2003 Roth has been designing a series of tables and shelving units. With this venture, Roth has succeeded in a perfect marriage of

art and object, making something that is completely functional. The pieces are manufactured in Richmond from laser-cut steel that’s subsequently painted and assembled in eye-popping juxtapositions of color. They are available through Artware Editions in New York.

When not creating art or shelves, Roth writes. He recently completed a textbook: Design Basics: 3D (Wadsworth Cengage, 2011) co-authored with Stephen Pentak, a follow-up to their previous book, Color Basics (Wadsworth Publishing, 2003). Roth is also the co-editor of Beauty is Nowhere: Ethical Issues in Art and Design (G&B Arts International, 1998) and has written a play titled “The Crit.”

Seipel lauds his colleague’s versatility, creativity and influence. “Richard’s works as a designer and as a fine art painter are garnering national and international attention,” he says, “adding to the conversation in both disciplines.” He adds: “His leadership as chair of the VCUarts department of painting and printmaking has been in large part responsible for the national recognition of its graduate painting program.” Inspiring and unconventional, Roth’s artistic journey is an invaluable example for his students as they find their own voices.