Lenny Lyons Bruno limns her hard early life through mixed-media quilts.

Lyons Bruno feat

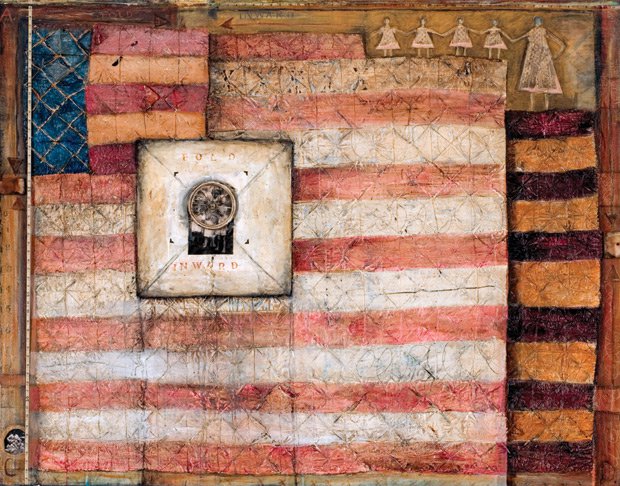

“Fold Inward,” mixed media painting 72″ x 56″

Lyons Bruno media

“King Coal,” mixed media painting 56″ X 72″

When you first meet artist Lenny Lyons Bruno in her Lexington studio, she seems sophisticated, sure of herself, yet easily approachable. She has the flat, no-accent voice of a broadcaster. An 8-by-8-foot easel leans against one wall of her studio. The rest of the spacious concrete-floored room is home to interesting old gewgaws she has collected over the years—an antique plow, a corncob dryer, and a vintage tricycle that won’t be used again. (“It can hang around,” she says.) In the center of the room is her work surface, sort of a gigantic butcher’s block. This is where she plots out the large-scale, mixed-media canvas-backed quilts that are her specialty.

Lyons Bruno doesn’t have a conventional “artistic” background. She didn’t go to art school—or any college. She left high school at 16, when she married. But she does have something that many artists who produce arresting works possess—a compelling history of personal struggle. Lyons Bruno grew up impoverished in Cranberry, West Virginia, a coal company town where money was scant and art nonexistent. In fact, indoor plumbing had yet to reach Cranberry when Lyons Bruno lived there in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Her father was a coal miner; her mother raised nine children. “We lived in the hollows, where our clan was all we saw,” says Lyons Bruno, now 62. “We only socialized with family, but it was a humongous family.”

After she married her husband, Rick, then studying to become a commercial photographer, she joined him on shooting trips around the country. Half out of boredom, half seeking a means of self-expression, she started taking pictures herself, and painting as well. Rick says she was a natural talent. “Lenny’s first roll of film produced an image that won a $1,000 Best In Show award.” As their careers grew, they both sold photos to museums such as the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art and the Detroit Institute of the Arts. The couple made a living traveling the outdoor festival circuit for more 30 years, selling their photographs and paintings at dozens of shows each year. They lived in Florida, then Georgia before eventually “retiring” to Lexington about three years ago. They had been introduced to the town by the original owner of the Lexington Art Gallery, which the Brunos now own. “We fell in love with the area and decided this was where we wanted to live,” she says.

It was then that Lyons Bruno committed herself to producing the autobiographical, three-dimensional quilt works for which she has become known—to the extent that someone who’s not much interested in exhibiting or selling her work can make a name for herself. She layers paint with pieces of old things (the corner of a book cover, for example, or a strip of an old piano key) and found curiosities (an antique horse muzzle or the wheels off a pram) on canvas-backed quilts that have been gessoed. The quilts are as much a part of her story as coal mining—and they take gesso as nicely as canvas does. “We didn’t have art growing up,” she says, “but we had quilts. Lots of quilts.”

Lyons Bruno’s most recent collection, “Coal Camp Series,” may be her strongest. Comprising 18 large and small works, it limns the early life of this coal miner’s daughter, drawing from sources as personal as her mother’s journals, found after her death, and her own memories. The title painting depicts the cluster of company-owned houses where miners’ families lived and traded work for food and sundries at the company store. “We had to get everything from the company,” Lyons Bruno says. “We were very poor.”

Winters in the West Virginia hills were hard times and got worse when her father was laid off from the mines. Lyons Bruno was 6. “There was nothing coming in,” she says. So the family moved to Pennsylvania, north of Pittsburgh, where things weren’t much better.

When Lyons Bruno was in fifth grade, her mother (with help from children) canned 134 quarts of blackberries to keep food on the table through the winter—an experience she refracts in her work titled Blackberry Winter. Enclosed in the central figure, which represents her mother, is a small house echoing those in “Coal Camp.” Lyons Bruno commemorates her mother’s ability to create comfort and warmth in the family homes, even without conventional comforts—including food. Another piece, Fold Inward, shows a photo of a 2-year-old Lenny posing with her mother and two older siblings. They were hill people, entrenched in their clan. “None of us is looking at the camera,” she notes.

Other works in “Coal Camp Series” strongly evoke the working-class world. In Navigation Without Knowledge, for instance, Lyons Bruno uses a blackboard-like background to illustrate the family’s transition to a new life in Pennsylvania. “I was torn between two worlds,” she says—“the coal camp, where I was accepted, and school, where I wasn’t.” Likewise, the central blackness of the sprawling King Coal—56 by 72 inches—illustrates the foreboding entrance to a mine.

Even Lyons Bruno wonders, sometimes, what the message might be. “I have no clue why I do what I do,” she says. “Just that I am compelled to do it. It is so intuitive that in the beginning I don’t know what I’m going to do. When the piece is resolved, I find the meaning.”

Lyons Bruno doesn’t really want to sell her art, especially the “Coal Camp Series.” But she would like it seen, so she is devoting herself to getting the series shown in museums. “I think it’s important, and I want to share it,” she says. “You take your past with you …. These paintings are [my way of] coming to terms with it.”