Pamplin Park has two museums, three houses.

Historical interpreters at Pamplin Park.

Private Aaron Joseph, Second Connecticut Heavy Artillery.

Seven minutes south of downtown Petersburg lies a little-known Civil War complex that deserves a lot more attention than it gets. It is called Pamplin Historical Park (a name that gives no clue as to its identity), and it contains two Civil War museums, three historic houses, a military encampment and miles of trails through important battlefield fortifications, all of which could happily occupy a family for half a day.

Situated on 422 acres, Pamplin Park is is the site where both North and South dug in for the long siege of Petersburg and where the “breakthrough,” when it finally came on April 2, 1865, signaled the end of the Confederate States of America. The uniqueness of this place comes not so much from its battlefields, which are standard fare at Civil War parks throughout the South, but from its focus on the individual soldier. Where most Civil War sites concentrate on generals, politics and military tactics, this one looks at the conflict through the eyes of the 3 million rank in file in the war—the foot soldiers—men who fought, suffered and died without ever knowing much about the strategy going on over their heads.

Whether Yankee or Confederate, black or white, foreign-born or American, male or female, the daily life of the common soldier is the focus here. All aspects of troop life—encampments, food, music, worship, punishments, photography and medical treatment—are portrayed in realistic settings, not as examples of North or South, but as examples of either. The similarities between the opposing troops were always greater than the differences—one of the poignant aspects of every civil war.

The National Museum of the Civil War Soldier is the largest attraction in the park. Borrowing an idea from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C., this museum encourages visitors to choose a real soldier to “accompany” them throughout their visit—someone who actually fought at Petersburg and left records of his thoughts in letters and diaries. At the end, visitors learn the fate of “their” soldier—whether or not he lived to go home when the war ended a week after the fall of Petersburg.

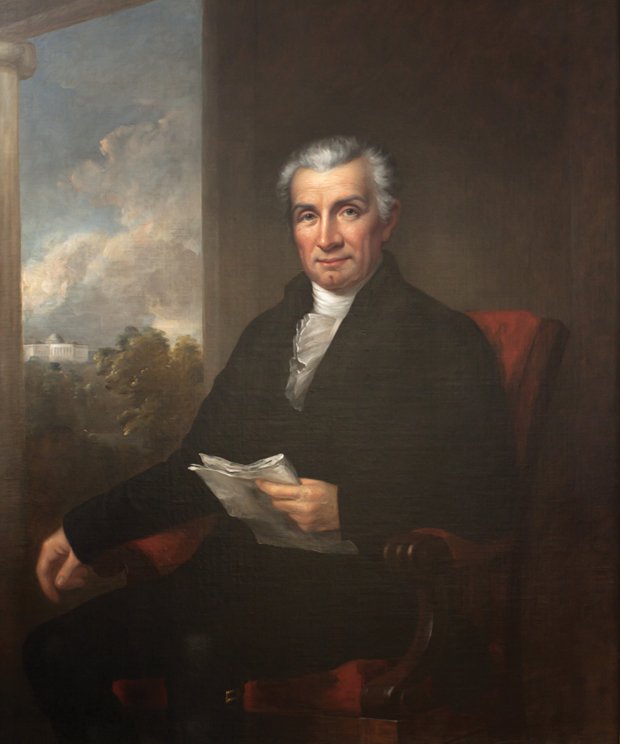

Tudor Hall Plantation lies between the park’s two museums. Built in 1812, this modest Virginia plantation home became the Confederate headquarters during the siege of Petersburg. It is portrayed in both its guises—half its rooms are furnished as a military headquarters and half as the Boisseau family home as it looked when the ancestors of Robert B. Pamplin Sr. lived there.

Of course, few in the Army had the luxury of a roof overhead, and the re-created Military Encampment shows visitors the huts and tents where soldiers and most officers lived. Most visitors will stay in the park long enough to need a “time-out” at the Hardtack Café, which sells sandwiches and drinks.

Robert Pamplin Sr. was born a few miles away from the museum, studied at Virginia Tech and began a career in the lumber business that ended with his retirement as CEO of Georgia-Pacific. Today, he and his son own the R.B. Pamplin Co., a private conglomerate with holdings that vary from concrete production to Christian bookstores. Robert Pamplin Jr. has written 13 books and, according to the company’s website, has eight degrees—including two Ph.D.’s. The company’s annual sales total about $650 million. Pamplin father and son bought back Tudor Hall in the early 1990s and began turning the property into the impressive Civil War museum it is today.