A “true history” of how Thalhimers department store was founded, managed by three subsequent generations of the family and grew into a 26-store chain.

Finding Thalhimers

Finding Thalhimers by Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt, Dementi Milestone Publishing, $25.00

War, racial unrest, hostile takeovers, fires and floods. That’s a lot to pack into one book, especially when it is primarily about a department store. But Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt does exactly that in Finding Thalhimers, which explains how her immigrant ancestor opened a small dry goods store in Richmond in 1842, weathered hardships and passed leadership off to three more generations of Thalhimers. Over 150 years, the small business expanded until it took up an entire city block on Broad Street between 6th and 7th, and then grew into a 26-store chain that spread across Virginia, Tennessee and the Carolinas. Smartt juxtaposes this impressive growth against the backdrop of changing times, blending the store’s history with Richmond’s.

When the city was ravaged during the Civil War, Thalhimers used blockade-runners and adjusted inventory to meet the public’s needs. As Smartt writes, “Men wore shoes with wooden soles when shoe leather became too expensive. Fat doubled for soap.” During the Depression, the store pinched pennies to stay afloat: “In order for an employee to get a new pencil, he had to turn in the stub of the old one.”

The hard times passed, and then came the post World War II boom. Thalhimers, aiming to become more competitive with its upscale, cross-street rival, Miller and Rhoads, began importing haute couture from Europe and became a hub for shoppers throughout the state. Writes Smartt: “Thalhimers was the only department store in the country to offer showers, an especially popular feature for rural shoppers coming to the ‘big city’ for the whole day.”

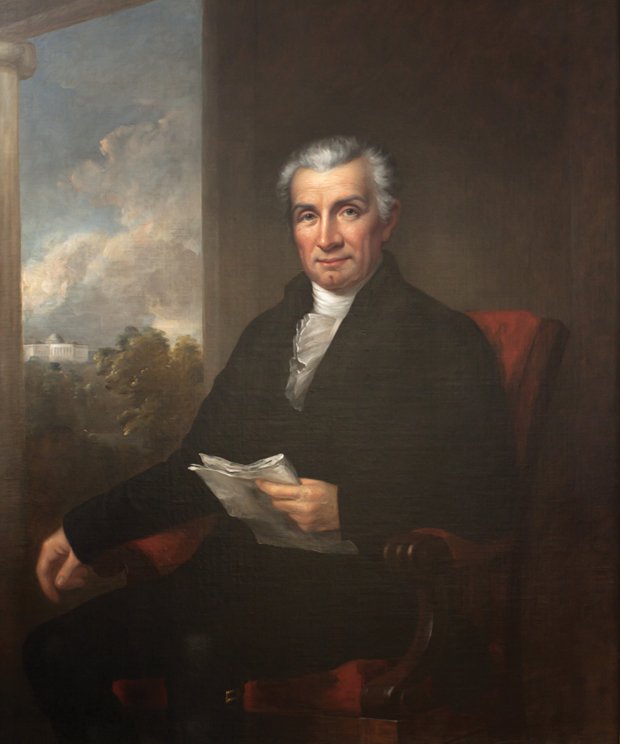

Much of the book’s focus is the great American success story, but that is not to say that everyone is portrayed as glamorous and fault-free. The men running the store are described candidly as the complex individuals they were. William Thalhimer Sr., who died in 1969, was a shrewd and cutthroat businessman who let nothing interfere with the bottom line. He revoked store discounts from his sisters’ families and forced his uncle out of the company, calling him “a piddler.” He once hung up on his son, who was boasting of a promotion, explaining that a written letter would have served the same purpose at less cost. However, this same frugal businessman financed a wildlife preserve at Richmond’s Maymont Park so that “low-income, urban families could step off a city bus and see everything from bison to foxes to black bears in their native habitats.” Complex, indeed.

Thalhimers was noted for some disparate achievements—among them, having the longest continuous display window in the United States (90 feet), for being the first business to install aluminum siding on a commercial building, and for taking a stand against racism. “Thalhimers,” Smartt says, “was the first retail establishment in Richmond to fully integrate.” Here she proudly pulls a yellowed slip of paper from a folder. It is a telegram from John F. Kennedy inviting Smartt’s grandfather, William Thalhimer Jr., and other business leaders to the White House to discuss equal opportunity.

Though she is proud of the fact that her grandfather helped to promote civil rights, Smartt doesn’t shy away from noting what came before that positive step. In 1960, the store employed people of all races and they all ate together in the break room. But where customers were present, things were different: the main restaurant served whites only and the fitting rooms and bathrooms were segregated. Until, that is, black students from VCU staged a sit-in on February 22, 1960. That was the true impetus to change. “I just tried to be honest,” says Smartt, who is a freelance naming consultant in Richmond. “I wasn’t trying to write an exposé, nor something that was a PR-piece either. The store’s gone, so I wanted to tell the true history and I didn’t leave anything out.”

Smartt spent a dozen years interviewing family members and former employees, poring through records, and conducting library and legal research. “There were a lot of surprises,” she says. “I found out the firm went bankrupt in the 1870s, which was not a story that was passed down. I didn’t realize there had been any failure. Then during the Depression, they almost went bankrupt again. They borrowed a huge sum of money from a friend in New York. It was just a gentlemen’s agreement; there were no contracts. This was back when businessmen would help each other out. My grandfather, who was 18 at the time, carried the money down from New York in brown paper sacks and slept with them under his head on the train.”

Along with the 12 years of research she’s compiled, Smartt has collected anything she could find with a connection to the store. Her guest room has been transformed into the Thalhimers Memorabilia Room. The beds are blanketed with framed photos, some more than 100 years old; a desk is covered with coffee mugs, dessert tins, and shopping bags, each of them embossed with the Thalhimers logo; and the prized possession sits pinned between the glass and felt of a paperweight—an 1842 silver dollar that was removed from the store safe when the flagship store in downtown Richmond closed its doors for the final time in 1992.

Lingering in this room, touching the items spread out before her, Smartt is able, in some small way, to revisit the store where she had spent so much of her childhood. “I want to honor the four entire generations of work that went into building this store,” she says, “and make sure that their story doesn’t die.”