Great Falls is battling to remain a rural redoubt against the tidal wave of Northern Virginia development. But how long can the tony enclave hold out?

The green of the Great Falls Village Center.

Walt Lawrence, who moved to Great Falls from McLean in the 1970s.

Adeler Jewelers’ storefront.

Great Falls Creamery.

Colleen Sheehy Orme.

Fresh ice cream from Great Falls Creamery.

Weaver Vad Moskowitz, a resident of Great Falls since the 1960s.

Inside the Ginny Beyer Studio.

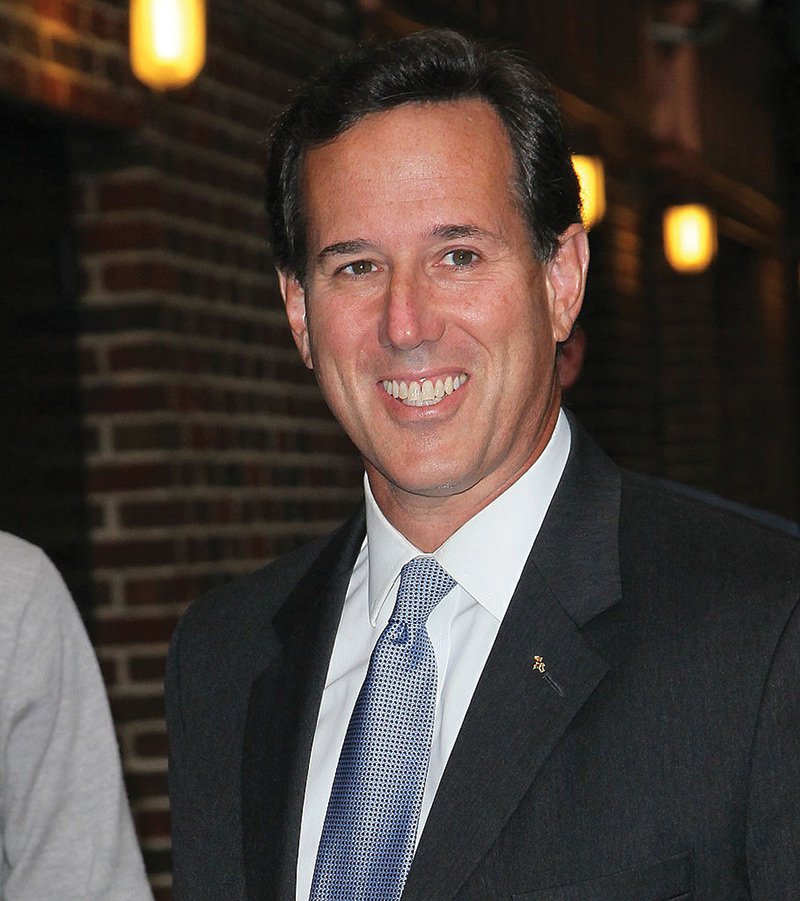

Rick Santorum.

Opening moments from a Great Falls Easter egg hunt.

The Forestville schoolhouse, built in 1889.

Adeler jewelry on display.

Photography by Sarah Cramer Shields

The first sight of unrestrained greenery upon heading west into Virginia from Washington, D.C., is the town of Great Falls, a leafy refuge for the power players that brave the Beltway every morning. Here, twisting country lanes converge on a town center with a green, a local coffee shop, and store owners who call their customers by name.

These trees, pastures and open space—only 17 miles west of the White House—don’t come cheap. The town has a median real estate price of $1.7 million (homes have sold for $8 million and up), putting it in the top 10 percent of Virginia neighborhoods. Residents include Washington Redskins owner Dan Snyder, political speechwriter Peggy Noonan and former presidential hopeful and senator Rick Santorum. One could say it’s the Beverly Hills of the D.C. metro area. But unlike the self-promotion of Rodeo Drive, this town is all about discretion.

Here, despite its roster of boldface names, people make an active effort to create a close-knit community, tied together by history and traditions in what some would describe as the often-rootless northern Virginia area. There’s a town square with a white painted gazebo right out of an Andy Hardy movie, a weekly gathering of vintage car enthusiasts and an annual Easter egg hunt with gemstones from a local jewelry store hidden in eggs for a lucky few.

But all does not rest easy in this picturesque village. Even wealth does not make the town immune from the drumbeat of development. Great Falls’ convenient placement between Route 7 and the tireless busyness of the Beltway makes it a prime target for developers.

The town’s population has nearly doubled in the past decade; with the kind of new neighborhoods many residents here were once looking to escape becoming more common. There have been several campaigns to widen Georgetown Pike, the historic byway that winds its way through town, that have been thwarted for now, though a proposal to turn a 50-acre meadow into a cluster development is currently being hotly contested by local residents. It’s the last community in Fairfax County that has retained its rural heritage, and many here want to keep it that way.

Located along the Potomac River and adjacent to the 800-acre national park of the same name, the village of Great Falls was originally known, unofficially, as Forestville, until it was named in 1955, later including several other small communities in the area after a new post office was built in 1959. (Early farm settlements began to form in the area as early as the late 1700s.)

It is bisected by Georgetown Pike, Virginia’s first scenic byway, a designation that makes it illegal to widen the two-lane road. The 12 undulating tree-lined miles of the pike began as a buffalo run and became a trading road as early as the 18th century, with construction of the toll road beginning in 1813 to facilitate the transport of goods (crops, sheep and tobacco) from western counties to port cities.

“Until 30 years ago, the community was considered to be too far out from D.C. Offices and homes and land were cheap. So government workers who were willing to do the long commute could afford to live there. People enjoyed owning large lots of five acres or more,” explains Karen Washburn, 66, a local historian who has spent more than 35 years doing research on Great Falls.

Today, the traffic of the Beltway and Route 7 races by Great Falls’ eastern and southern edges, partially because the pike—which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012—has capacity limitations, and partially because the area is on well water and not sewer, over time Great Falls has resisted the urban sprawl that quickly changed surrounding Fairfax County farmland into suburbs and shopping malls in the second half of the 20th century. Fairfax is the most populous county in Virginia by far, with 1.1 million residents and a growth rate of 3.3 percent, far exceeding the state’s overall growth rate of 1 percent.

The increasing rarity of open land in northern Virginia has meant prosperity for Great Falls. As of the most recent census, among a total population of around 15,000, the median income was $229,200. More than 80 percent of the population holds college degrees and only 1 percent lives below the poverty line. (In comparison, in Fairfax County, the median income is $104,259, and 59 percent of the population have college degrees; 6 percent live below the poverty line.)

Great Falls’ public secondary school, Langley High School, is ranked within the top 100 public high schools in the country, and second in the state, by the 2015 U.S. News and World Report. A neighboring private boarding school for girls, the Madeira School, established in 1906, is ranked as one of the most expensive and elite prep schools in the nation, with a well-known equestrian program and distinguished alumni including former Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham, actress Stockard Channing and author Julia Reed.

Ginny Brzezinski, 51, and her family moved to Great Falls in the summer of 2014 for the space, small town feel—and the schools. “I spent a lot of time looking at high schools, both public and private. At Langley, walking around in the hallways, I saw the kids were so engaged,” the mother of two high school students explains. And, she adds, laughing, “It’s free.”

The prominence of some of the 25-square mile town’s residents—who also include former CIA director Stansfield Turner and members of the Saudi royal family, among others—is one reason why the area has been able to fight development.

In the 1950s, when the Virginia Department of Highways and Transportation first attempted to widen the often-bottlenecked Georgetown Pike, then Senator John F. Kennedy, whose home Hickory Hill was located nearby in McLean (and would later become the home of his brother Robert Kennedy and his family until 2004) joined in successfully fighting the proposal to keep the pike one lane. People liked their serenity then, and they like it now.

Today, early town square mainstays remain, including the stately brick two-story Grange built by the local farming community in 1929. At the time it served as the center of town activity for both business and entertainment. Public meetings are still held here, along with events like holiday craft fairs and weddings. Adjacent to the Grange is the original two-room Forestville Schoolhouse, built in 1889, which has also served as a library, bank and post office over the years and is now available to rent for private events. And across the street is the Great Falls Village Center with restaurants, boutiques, doctor’s offices, and the town’s only gas station.

It is here that residents gather for town traditions organized by the non-profit Celebrate Great Falls—summer concerts and a Fourth of July parade that winds past the shops with a cavalcade of antique fire trucks, Girl Scouts, and stilt walkers all bedecked in patriotic bunting. Families in red, white, and blue lean against the low stone walls and cheer on the procession, and small children chase after the candy that is thrown from the floats. The parade ends with a cookout on the green with the newly awarded Young George Washington and Little Miss Betsy Ross.

On Sunday evenings the green is also used for summer concerts. Residents stretch out on blankets and lawn chairs while listening to music from local bands playing in the gazebo. Children play Frisbee at the edge of the green.

The slower pace of life is what drew 76-year-old Walt Lawrence here in the 1970s from neighboring McLean: “It’s close to D.C., yet I live out here in a very bucolic environment. Beautiful scenery, incredible wildlife.”

Now retired, he’s decided to capture local natural beauty while it lasts by taking up wildlife photography. “Driving up Interstates 81 and 66 for years,” he explains, “I just saw the beauty disappear year by year.”

He is now a member of the Great Falls Studios, an organization of more than 100 local artists working in media ranging from quilt making to calligraphy.

“About two years ago, I got my first good eagle pictures,” says Lawrence. “Once I [realized] I could shoot eagles in my own town that felt like the top of the mountain. And egrets. I didn’t even know egrets were in the area. It’s a great thrill to see that this sort of wildlife still exists.”

Vad Moskowitz, 79, a weaver and another member of the Great Falls Studios, agrees that it’s the area’s rural heritage that makes it unique. “It has the last real registered agricultural farms in Fairfax County up here where I live,” she says. “There’s still a 600-acre farm, along the river.” She tells a familiar story, of moving here in the ’60s from Alexandria and choosing Great Falls because of her desire for space and a beautiful view. “People moving here were looking for something different,” she says.

Moskowitz recalls when the younger of her two sons was born 50 years ago, she had to be airlifted out to the hospital because there were 20-foot snowdrifts along her unpaved road: “We were always the last place to be plowed then because there were so few of us. Amazing how well they take care of the roads now.”

“Great Falls has only been known for large estates and prominent residents in the last 30 years. Before that it was a community of farmers, both dairy and market gardeners,” says Washburn, the historian. “The suburban development of the early 1970s began the change from farming community to bedroom community. The rise in property taxes made farm land too expensive for dairy farmers and market gardeners.” (The last active dairy farm was sold in the mid-1980s.)

Colleen Sheehy Orme, 52, who grew up in Great Falls and then moved back as an adult in her 30s, remembers, “The town was not as densely populated when I grew up here. There was a ton of land, a ton of farms as well. Horses would occasionally run through the front yard because they got loose.”

Brooks Farm, a working horse farm and one of a handful of remaining Great Falls farms, was sold in 2012 to luxury estate developers Basheer & Edgemoore. The developers are proposing rezoning the 52 acres from their agricultural designation to cluster zoning, which would allow for denser development.

Mark Fields, vice president of land development and acquisitions for Basheer & Edgemoore, contends that cluster zoning would actually help to keep the new development harmonious with its surroundings. “Cluster achieves more lots, but what cluster provides is public space,” he says. “Cluster allows lots to be smaller, which allows minimized private area and maximized public area. Under cluster zoning, 40 percent is to be common space. Over 41 percent will be common space under the current version of our plan.”

Fields also says that his company has been working with local groups and adjoining property owners to ensure that the unique environment of the village will be protected and the houses will be compatible with the neighboring subdivisions.

But some, like Sheehy Orme, do not support the plan. She began a petition in 2014 against cluster zoning, gathering more than 800 signatures. “You can’t stop development, but you have to do responsible development,” she says. “People haven’t thought out the long-term implications.”

So far, Great Falls has remained a “large lot” community. There are no apartment buildings, townhomes or condos within its boundaries. Residents like Sheehy Orme worry that could soon change with the possibility of rezoning for Brooks Farm, and another former farm that is now an open meadow near the town center, on the table. If the developers succeed, it could open the flood gates for the same sort of sprawl that Vienna, McLean and the rest of Fairfax County have seen.

Since Great Falls is technically not a town, but rather a post office address area, its residents have no official government representation. The Great Falls Citizens Association was formed in 1968 to address this issue, and works with the Fairfax County supervisor to communicate local consensus. Eric Knudsen, president of the association, admits, “We’re land zoning conscious.” Brooks Farm, and the potential it brings for cluster zoning, he says, is a source of worry.

But resisting development comes at a price—in convenience. Great Falls currently only has one small Safeway grocery store, in the Village Center, and though there has been talk about adding other choices to the small shopping area, such as a Whole Foods, there just isn’t room.

What it lacks in size, the diminutive retail district makes up for with an eclectic mix of shops and restaurants. The Ginny Beyer Studio sells handmade quilts, and the Great Falls Creamery offers all-natural ice cream made from milk from grass-fed cows.

Adeler Jewelers is the Village Center’s mainstay, opened in 1975 by Jorge and Graciela Adeler shortly after they arrived here from Argentina. Now it is a three-generation owned family business with the Adelers’ grandchildren beginning to learn the jewelry trade. (The Adelers donate the gems tucked into Easter eggs each spring.)

And the Old Brogue, a wood paneled and Guinness-on-tap Irish pub, has been the local watering hole for 35 years. The pub is unpretentious, serving typical bar fare and authentic Irish dishes, but the constantly packed parking lot attests to its appeal to residents of all ages.

Though its small town vibe may make Great Falls seem a world away, the area is actually less than 15 minutes from Tysons Corner, the 13th largest mall in the country and the largest in the Baltimore-Washington area. The expansion of the Washington Metro to Tysons in the summer of 2014 has only increased the pace of the urbanization spreading west. As with everything else in Northern Virginia, the face of Great Falls is changing—perhaps a victim of its own success.

Still, hopes remain high that Great Falls will continue to be a community where the anonymity of newness has not quite infiltrated, and a more traditional sense of place remains.

For Sheehy Orme and others, it’s a place worth fighting for. The sort of place that once compromised, could be gone forever. Great Falls, she says, is “a rare gem.”

For information about Great Falls’ community events, go to CelebrateGreatFalls.org

This article originally appeared in our June 2016 issue.