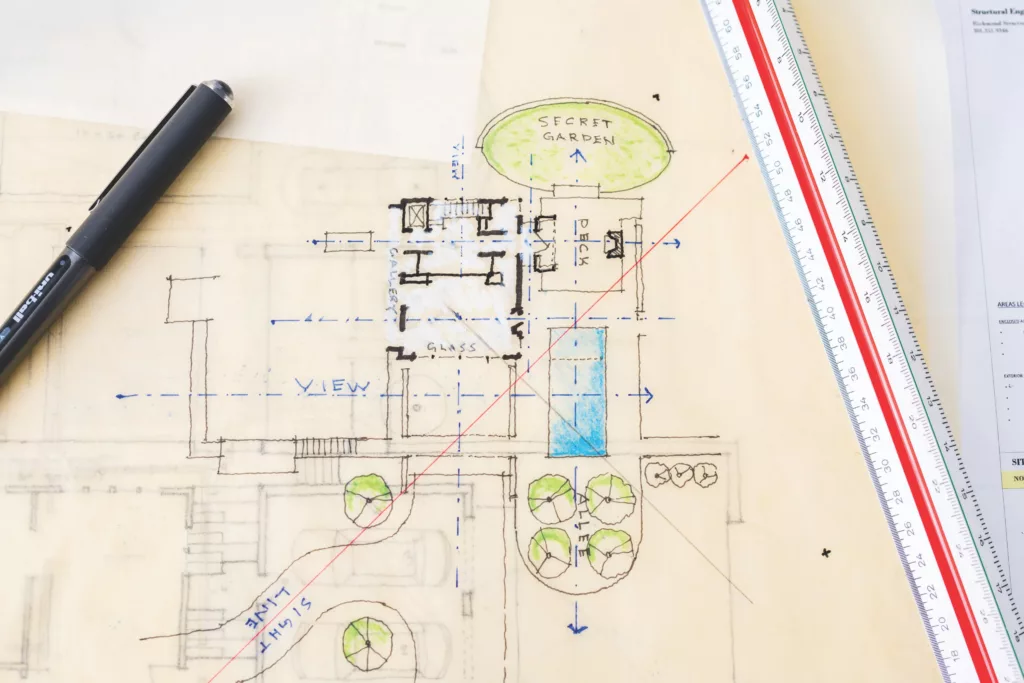

It’s an unassuming sketch that begins with a single square, a squiggle of a hand-drawing.

Page after page, the square has been added onto, enlarged and articulated into bolder iterations, until a fully formed vision for a new structure emerges.

“There’s a sequence over a week,” McCullar says. “The big ideas come very fast.” It’s taken him decades to develop his process—with stellar success.

Richmond-based Josh McCullar—considered by many to be the most gifted young architect practicing in Virginia today—discovered his career path early, inspired by common materials and rural forms.

His father was an industrial engineer working at cotton mills in cities of the Upper South, back when textiles ruled. McCullar was born in Danville and grew up in mill towns across the Carolinas, where corbelled brickwork laid by masons in mill buildings informed an observant mind.

In nearby fields, vertical barns towered 20 feet above parallel rows of tobacco. Some were timbered, others clad in cedar or tin, but all were built for one purpose: to cure harvested leaves inside well-proportioned structures laid atop leveled fieldstone stacks.

An influential anchor was a 50-acre farm that his family owned for six generations in Franklin County, North Carolina. Once a tobacco farm, vegetables are now its main crop, and as a site for family reunions, it connects generations. McCullar’s annual sojourns there offer an opportunity to reconnect with cousins, aunts, and uncles—but also to re-examine his elemental roots.

He spent much of his youth as an artist, a maker, and an observer in that agrarian world.

By the time he was 10, his mother, a schoolteacher, enrolled him in classes for drawing, painting, sculpture, and photography that would continue well into his late teens.

When he was 17, knowing he’d need a portfolio for admission to design school, a teacher suggested his mother send him to Glasgow, Scotland, for a summer watercolor workshop. There, he discovered the works of artist and architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh and iced that cake with tours of castle ruins in Edinburgh.

“Looking back on all this,” McCullar says today, “I don’t think there was ever another more obvious path for me.”

In an unexpected and seminal moment, architect Josh McCullar was commissioned to design an addition for Epiphany Lutheran Church in Richmond. Here, senior pastor Phillip Martin enjoys the church’s new Commons’ space that looks toward a new outdoor terrace. A laser-cut metal scrim referencing the Holy Trinity filters light from the sunset and incorporates themes important to the church. Photography by Ansel Olson

An Old Soul

By 1996, he enrolled at North Carolina State’s College of Design, a hotbed of modern architecture. There, Ellen Weinstein, faculty member and partner in Durham-based with/Architecture, taught McCullar twice: first in a sophomore foundation studio, then in a senior architecture studio.

She first saw an 18-year-old designer who arrived at school knowing what he was meant to do and how to make his work timeless. “He was an old soul of an architect, even before he started studying,” she says. “Somehow, he knew proportion, scale, material, craft, and making beautiful experiences.”

McCullar would show Weinstein what he’d drawn, then redrawn and drawn again when he didn’t have his proportions right. “He worked at an iterative process,” she says. “And he’s honed it over the years. He wants to do the work, not just get the work.”

In 2000, he enrolled as a graduate student at University of Virginia’s A-School, studying with the talented W.G. Clark, a 1965 UVA graduate who was later appointed chair of architecture at UVA and still teaches there today. He remembers McCullar as particularly tenacious. “I was very impressed with him as a very serious guy and someone who was quite determined in his own world,” Clark says.

In 2002, McCullar earned his master’s degree in architecture from UVA, and a year later went to work for Richmond-based SMBW, a firm known for its modernist bent. They were tapped as executive architects for the Clark-designed addition to UVA’s Campbell Hall, which houses the A-School. “W.G. would fax sketches to us and we’d put them into a computer and develop working drawings for his review,” he says. “It was like: Here’s the start of an idea, and you guys make it work.”

The Poetry of Placemaking

On his own in 2016, McCullar entered a design competition for an addition to Epiphany Lutheran Church in Richmond. His first comment to the pastor was that he was not a church architect. Then he discreetly noted that the church was located on the highest point on Monument Avenue west of the State Capitol.

While his competitors talked programming, McCullar spoke of architecture as the poetry of placemaking. And he found a client that was simpatico: the pastor had not only attended NC State, but was a friend of the head of its School of Architecture, David Hill. “He could understand me because he spent four years with an architect in school,” McCullar says.

The competition won, he got to work.

Richmond-based Ballou Justice Upton Architects had designed the sanctuary and cross tower facing Monument Avenue in 1959. Their intended canopy over a walkway from parking lot to sanctuary was left unbuilt, so McCullar created a new one. He then connected a 7,200-square-foot addition to the 1959 sanctuary and a former chapel.

In a gesture addressing the path between this life and the next, he built a 170-foot garden walk along the cross tower—one of the church’s oldest buildings—and its columbarium, its newest. Landscape architects from Waterstreet Studio added native plants that encourages the congregation to discover a new outdoor sanctuary. “They could hold services outdoors during Covid,” he says.

A Polished Point of View

When Richmond artist Paulette Roberts-Pullen and her husband began researching architects’ websites for their Grove Avenue home, McCullar’s in particular resonated. “Josh’s looked very polished with a point of view,” says Roberts-Pullen, who’d also studied with Clark at UVA.

She and McCullar discussed a courtyard and forecourt out front, along with ideas for stately and modern designs. At 40-feet wide, the lot created a linear form—almost a shotgun-style layout where a distant fireplace, porch, and studio are visible upon entry. “It’s divided in an elegant way for the front and the back of the house—and I loved the way he resolved that,” she says.

The entry brings with it substantial historic precedent. Like Pavilion IX on the Lawn at UVA, its inset door pushes in, rather than out. “If there is a modern design on the Lawn, it’s the most modern because it’s reductive,” McCullar says.

The door at the Grove Avenue home is white oak, its handle is a bronze lever, and its brick is laid in a pattern that steps back from the entry, inspired by the intricate masonry of Southern cotton mills. But here, the brickwork projects a new elegance through its finish. “It’s a cube of white clay washed in lime,” McCullar says.

At the rear of the lot beside and behind the studio is a landscape by Anna Boeschenstein, founder of Charlottesville’s Grounded. It drops 14 feet from the bustle of Grove Avenue—and out of earshot. McCullar’s design embraced the quirkiness of the lot—wet at the rear, narrow, on a busy street—by organizing the house and its urban garden. It transitions from a semi-public space with a sunny forecourt in front to a very private rear garden. The result is a seamless integration, blurring the inside and out.

McCullar’s design embraced the quirkiness of the lot—wet at the rear, narrow, on a busy street—

by organizing the house and its urban garden.

This urban residence on Grove Avenue in Richmond completed in 2023 sits directly across from St. Catherine’s School on the only residential block between St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, built in the the early English Gothic style, and the notable early 20th-century commercial shopfronts of Westhampton. The location informed McCullar’s design: to create a home that would stand the test of time and hold a dialogue between modern and traditional.

The floor-to-ceiling window from the front elevation wraps the corner into the loggia and transitions to natural white oak cladding and a custom 10-foot door.

Transforming a Laburnum Park Residence

In 2018, Holly and Tom Scott called on McCullar to convert the first floor of their 1926 Laburnum Park residence into a space where they could age in place. As an afterthought, Tom asked for a screened porch. It would become a focal point for the house, a fusion of exotic woods woven in full.

Its posts are double-height, 8-inch-by-8-inch Western red cedar—and former tree trunks. Floors are durable Ipe, while Spanish cedar louvers control light, night and day. Above, three wooden ceiling fans provide ventilation. All were created in collaboration with Eric Olsten, a Richmond-based artisan who introduced himself to McCullar by gifting him a book on George Nakashima, a Japanese mid-century modern woodworker.

Interior designer Kelly Brown worked with Olsten and McCullar on a kitchen of quartzite counters, sapele mahogany panels, and white oak floors. A travertine-lined bath leads to a primary suite, both new.

Outside, McCullar created a re-ordered rear entry from a driveway. For a new garage’s cladding, he reached back to an ancient Roman technique of mixing powdered limestone and quartzite, adding water, and applying the slurry to walls. “It’s a time-tested ancient recipe in a modern, new use,” McCullar says. “It’s the same that was used on the restored State Capitol.”

The view from within the family room opens to an east-facing screened porch with custom cedar louvers, which are operable for privacy.

The screen porch, with a 14-foot-tall tongue-and-groove cedar ceiling, stretches like a scrim along the east elevation of the addition and is wrapped in custom operable cedar louvers

Heralding a New Chapter

McCullar’s compositions have formed the early foundation of a Virginia practice like none in

the state. They are at once timely and ready for restoration at any point over the next 200 years. He expresses the ambitious desire to see their bones—in the form of ruins—as they appear thousands of years from now. “Buildings should be beautiful and well-crafted, because the most sustainable building is a permanent one,” he says.

Today McCullar has a new residence underway between Granite and Libbie Avenues in Richmond’s West End, where lots are mere slivers, making functionality and geometry a challenge the visionary architect welcomes. His ethos is, at its heart, about placemaking that fosters a symbiotic union between architecture and construction where the structure becomes an extension of the landscape.

From the hand sketches that begin his process, McCullar is heralding an expansive and explosive new chapter for architecture in Virginia. Design aficionados are not likely to be disappointed.

This article originally appeared in the February 2025 issue.