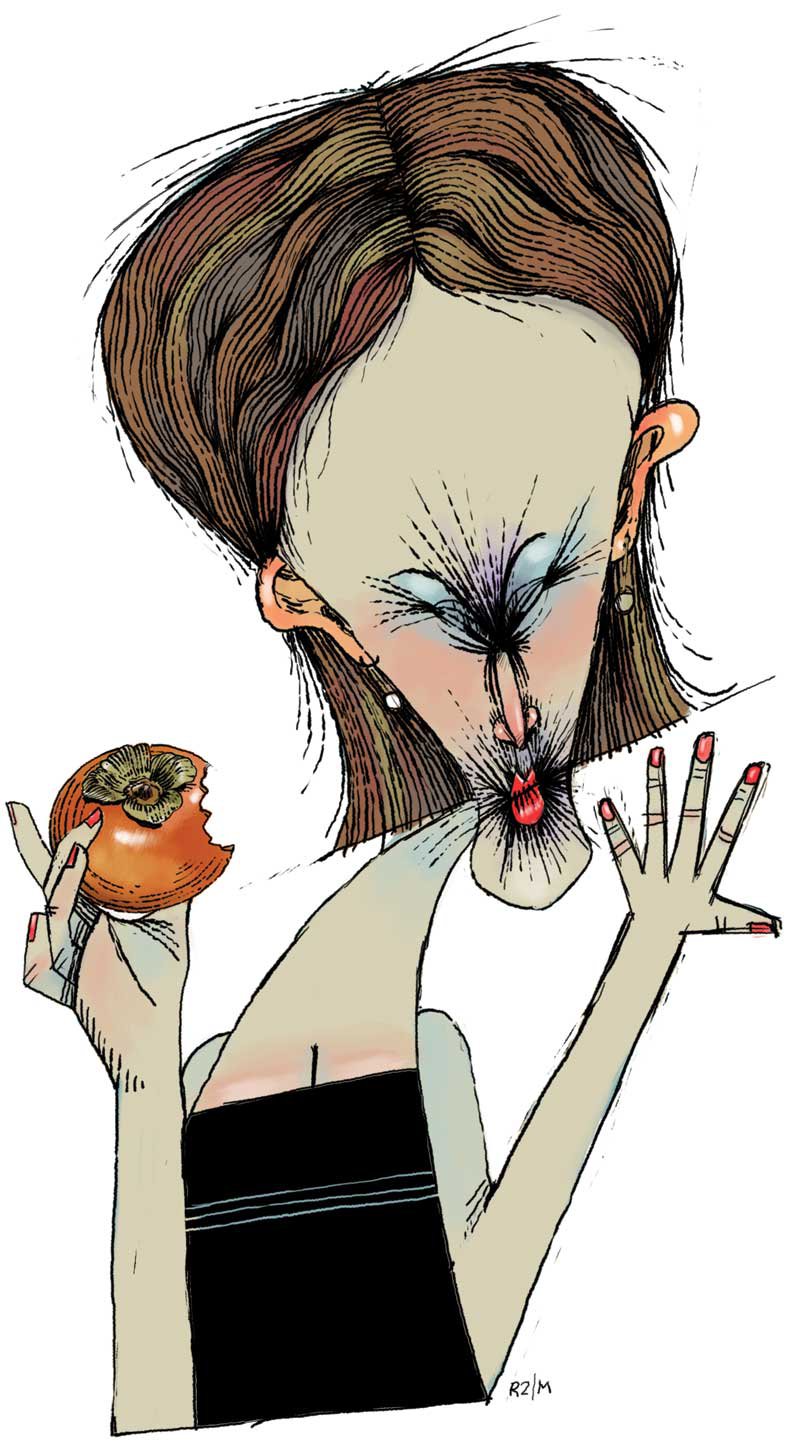

Succumb to sampling the unripe fruit, and you’ll never do it again.

Illustration by Robert Meganck

An unripe persimmon is a lovely thing to behold. A glossy, yellow-orange globe, a bright splash of color against the crisp blue of a clear fall day, it dangles plump and inviting from bare branches in the waning weeks of autumn.

An unripe persimmon, however, is a decidedly unlovely thing to eat. “Uncommonly puckery,” wrote Henry David Thoreau.

What happens when you bite into the unripe fruit of Diospyros virginiana, the American persimmon, is unpleasantly memorable, and yet difficult to describe. It feels like all the moisture has instantly been sucked from your mouth. Like your lips and tongue have been coated in a superfine layer of silt. Like you’ve eaten a mouthful of talc. Like a chalk-and-sandpaper sandwich with a chaser of aspirin.

The pucker is caused by the fruit’s very high tannin content. (You can approximate the experience if you have none handy—and possess, like your author, a fatally curious disposition—by nibbling sparingly on a bit of greenish banana skin, which is also high in tannin.) Tannins are a class of astringent chemical compounds found in plants that cause the constriction of body tissue. Astringent tannins are why your skin feels “tighter” when you apply witch hazel, the extract of another high-tannin plant, and it is from “tannin” that we get the word “tanning,” the process used to turn animal skins into leather goods. In your mouth, the tannins from a not-ready-for-prime-time persimmon bind with the proteins in your saliva to create that unpleasant and lingering sensation of having just taken a big swig of shredded cotton balls.

Tannins, which also give strong tea and wine their particular mouth feel, are complex substances. They seem to benefit plants in a variety of ways, including offering antifungal and antibacterial properties as well as discouraging predators. As high-tannin fruits like persimmons ripen, the tannin content diminishes while the sugar content increases, so that the fruit becomes palatable when the seeds are ready to be spread by creatures that consume it.

Persimmons, though, are a very late-season fruit; it’s often recommended to wait until after the first frost to gather them. And when you do, what you’re looking for is less like “ripe” and more akin to “rotten.” Like a tempestuous screen siren who ages into a venerated character actor, the persimmon is at its best and sweetest only when it has begun to wrinkle, sag and decay, a process known in horticultural terms as “bletting.” In fact, the best way to be sure a persimmon is ready to eat is to find it already lying on the ground—assuming the raccoons, opossums, deer, skunks, foxes and other creatures that like persimmons haven’t beaten you to the bounty. You can also shake the branches and collect any fruit that falls. Or, if you’re curious to try persimmons without having to fight the black bears, you can attend the annual Persimmon Festival Oct. 31 at Edible Landscaping in Afton.

You might want to go easy on gorging on the fruit, however. In rare cases, persimmon consumption has been linked to the formation of bezoars—a stony mass of indigestible materials lodged in the stomach or elsewhere in the digestive tract. There’s actually a name for this very particular type of bezoar: a disopyrobezoar.

Still hungry? Scrape the sticky, sweet pulp from the skin and eat it straight from the spoon, spread it on bread, or use it in cakes, cookies, puddings, pies, sweet breads and other recipes you can find all over the Internet. Persimmons have also traditionally been used to make wine and beer, and last winter, in collaboration with the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond’s Ardent Brewery resurrected a nearly 300-year- old recipe for persimmon beer from the Society’s archives. Ardent brewed about three gallons of Jane’s Persimmon Beer, resulting in a wine-like, low-alcohol beer, the sort of everyday beverage commonly consumed at the time.

The persimmon is a hardy tree that grows easily in the South and fruits abundantly, which is no doubt why the fruit found its way into so many recipes. Persimmon is related to ebony, and the wood, though apparently considered somewhat difficult to work, has traditionally been used to make decorative objects and golf-club heads (you can still order custom-made persimmon-wood clubs). It’s also an attractive landscaping plant, the brilliant color of its autumn leaves followed by the orange glow of its fruit. Plant one, and you can look forward to a sweet harvest to match the fall beauty.

And if you should one day commit the error of eating a persimmon too soon, there is always this consolation: It’s a mistake you are unlikely to make again.