Extreme wealth has always captured the American imagination. Among the great affluent class in Virginia, few have intrigued us more than the late billionaire philanthropist Paul Mellon and his wife Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon. From horticulture and the arts to education and sport, we explore their legacy in Virginia.

The Mellons in 1964 with Bunny’s daughter from her first marriage, Elizabeth Lloyd, attending a preview of the couple’s collection of English art at the Royal Academy in London.

Photo by AP Photo

Paul and Bunny Mellon, 1971.

Photo courtesy of AP Images

Paul Mellon

Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art

Mrs. Peel and Paul Mellon at the Piedmont Hunt.

Photo by Thomas Neil Darling, courtesy of the National Sporting Library and Museum

TUCKED NEATLY ON A BOOKSHELF behind a pickled oak door at the Oak Spring Garden Library in Upperville are a few dozen rare volumes of children’s fairytales and drawings, among them Little Songs of Long Ago, illustrated by Henriette Willebeek Le Mair, and Language of Flowers by Kate Greenaway. They once belonged to the late heiress Rachel Lambert Mellon, known all her life as Bunny. It was fairytales like these that inspired in her a passion for books and her well-known affinity for the natural world.

In a sense, her life was a fairytale. She was born in 1910 in Princeton, New Jersey to great wealth—her grandfather was the inventor of Listerine and her father served as president of the Gillette Safety Razor Co. In 1932, she married businessman Stacy B. Lloyd Jr. and for many years the couple enjoyed a close friendship with banking heir and billionaire Paul Mellon and his wife Mary Conover. Mary died from an asthma attack in 1946, and in the years following, Bunny divorced Lloyd and married Mellon in 1948. The couple traveled the world and maintained residences in Europe, North America and the Caribbean, but made their primary home a 4,000-acre estate near Upperville called Oak Spring Farm, where they entertained their glittering circle of the beau monde.

As glamorous as their life in society was, the couple had a higher purpose. In his 1992 memoir Reflections in a Silver Spoon, Paul Mellon estimated that the couple had given more than $600 million to charitable causes. Paul passed away in 1999 at age 91, and Bunny Mellon continued the couple’s philanthropy until her own death 15 years later. Among the beneficiaries were many Virginia institutions—including the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Virginia Historical Society, Virginia Tech, Hampton University, the Nature Conservancy, Virginia State Parks and a long list of museums, libraries and conservation organizations.

When Bunny Mellon died in 2014 at age 103, the Mellons’ combined legacy—the gifts they made to support the arts, horticulture, sport, education and scholarship—reflected their many and various passions and a deeply-held faith in philanthropy’s ability to change the world for the better.

Bunny Mellon in her garden.

WIDELY CELEBRATED AS A gardener, Bunny Mellon redesigned the White House Rose Garden in 1962 at the request of her friend Jacqueline Kennedy, and later, in 1965, the East Garden, which had been renamed in the First Lady’s honor. In 1996, when officials at the palace of Versailles in France sought to reconstruct the kitchen garden of Louis XIV, the Mellons provided financial support and Bunny offered counsel on the design. But as accomplished as she was as a horticulturalist, Bunny Mellon’s greatest legacy may be her library: she began reading and collecting books at a very young age and that inspired many of her other pursuits.

Though she did not attend college after her graduation in 1929 from the prestigious Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Mrs. Mellon delighted in collecting and poring through rare books and manuscripts, especially those about botany and horticulture. In fact, her skill in aquiring academic material rivaled that of many scholars. By 1980, her collection had grown so large the couple had to build a separate library on the grounds of Oak Spring in order to house the works.

Today Tony Willis is the librarian of the Oak Spring Garden Library, which comprises more than 18,000 books, manuscripts and other ephemera, some dating back as far as the 15th century.

Willis refers to Paul and Bunny Mellon simply as “Mr.” and “Mrs.” He began working on the estate in 1980 as a young man and eventually became librarian. In the original wing of the library—it’s been expanded since it was built—Willis gestures toward a table in the center of the room. It is bathed in muted light filtering through shades drawn to shield priceless books and art from the sunlight. “This is where Mrs. would come to do work, read a book, drink a Coke,” he says, going on to explain that Mrs. Mellon found the many books and works of art—including a large painting by Mark Rothko, one of her favorite artists—comforting. “She found inspiration here. For someone like her who had a lot of money and a lot of objects, there were always a lot of people involved. This was her private refuge.”

Oak Spring Garden Library, reader’s room.

Photos by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Oak Spring Garden Library, main book room.

Bunny Mellon’s beloved gardens provided another source of solace for the very private woman. It was a lifelong passion; she started transplanting wildflowers when she was just 6 years old and was designing gardens by the time she was 11.

Her garden designs at Oak Spring remain intact today. Mary Potter crabapples are trained over an arched pergola. Tidy paths carry wanderers up and down terraces laid out with plots for edible greens, perennial flowers and trimmed boxwood. Though carefully planned, the feeling here is natural and effortless. That was Bunny Mellon’s mantra: “Nothing should stand out. When you go away, you should remember only the peace,” she told the New York Times in 1969.

ART WAS A PASSION Paul and Bunny Mellon shared equally. In Reflections in a Silver Spoon Paul Mellon wrote about wealthy collectors he knew who substituted great works of art for friends, or sought immortality in gifting art to institutions. “I don’t think I have been collecting for any of these reasons,” he wrote.

Paul Mellon enjoying Edgar Degas’ “Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen” (1879-1881) in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Gallery.

Photo by Dennis Brack, courtesy of the National Gallery of Art

Paul began supporting art institutions in the late 1930s when he played a central role in the creation of the National Gallery of Art. Although the National Gallery had largely been the vision of his father, Andrew Mellon—the successful businessman, ambassador to the U.K. and secretary of the treasury under three presidents—who died in 1937, Paul carried his father’s plan to fruition, donating money and works of art, including masterworks from Raphael, Titian and Vermeer among others. In 1992, the value of Mellon’s contribution was estimated to be more than $142 million. “As we look to the future, I hope that you will consider the National Gallery as your gallery, for as Americans, its collections and resources belong to each of you,” he said in 1983.

Paul Mellon wrote in his memoir that his respect and admiration for great works of art came about “by a sort of mental osmosis.” His father, also a collector, owned and displayed paintings by artists such as George Romney and Sir Anthony van Dyck, and from a young age Paul appreciated the fine craftsmanship and strong emotion they evoked.

Yale University, Paul Mellon’s alma mater (class of 1929), was a special recipient of his largesse, including gifts of a building, works of art from his comprehensive collection of British sporting art, and an endowment to create the Yale Center for British Art.

The Mellons also gave significant support to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, donating major gifts and some 1,800 works of art. The couple helped make possible the construction of the VMFA’s west wing in 1985, and Paul Mellon served as a trustee to the museum for more than 40 years, making him one of its longest-serving supporters.

Among his many honors, he received five honorary degrees and more than a dozen prestigious awards, including the National Medal of Arts in 1985 and a National Humanities Medal in 1997.

Paul Mellon insisted that using his means for the benefit of others was his life’s work; Bunny felt the same way. Throughout their lives the Mellons supported numerous charitable foundations, including several that they founded: the Old Dominion Foundation (now the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, named for Paul’s father) and the Gerard B. Lambert Foundation, in memory of Bunny’s father.

“She liked to help people without everyone knowing it was her,” says Stacy B. Lloyd IV, Bunny’s grandson from her first marriage. “It was something she genuinely liked pursuing.”

PAUL MELLON WAS ALSO A passionate aficionado of the sporting culture, giving to many equine-oriented projects and charities. His Rokeby Stables, situated in the rolling farmland surrounding Oak Spring Farm, produced dozens of prizewinning horses, including Sea Hero, winner of the 1993 Kentucky Derby. In 1989, Mellon was named an “Exemplar of Racing” by the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga, New York, and remains one of only five people in the thoroughbred horse racing industry to receive the honor.

Paul and Bunny Mellon following Sea Hero’s 1993 win in the Kentucky Derby.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Bronze statue of Sea Hero on slate stone base at the National Sporting Library and Musuem by Tessa Pullan (English, b. 1953).

Photo by Tessa Pullan, courtesy of the National Sporting Library and Museum

In 1995, Mellon commissioned a bronze statue of Sea Hero to be installed in the boxwood garden at the National Sporting Library & Museum in Middleburg where, in 1999, he and Bunny would fund the construction of a new library building with a $1 million gift. The 2-ton, 8-foot-tall statue was installed in 2014. The Mellons commissioned other bronze statues of horses for NSLM, including one honoring the 1.5 million horses and mules killed in the Civil War.

But the Mellons’ legacy is not confined to brick, mortar and bronze, says Melanie Mathewes, executive director of the NSLM. “There is more than one person who walks through our door on any given day who has memories of Paul Mellon. They worked with him and encountered him in Middleburg. He was an icon,” she says.

“We who live in Northern Virginia have many reminders of Mr. Mellon,” wrote former director of the NSLM Peter Winants in 1999. Winants went on to tick off a long list of local places on which Mellon had left a lasting impression. Though Mellon preferred to think of himself as an amateur in all his pursuits, Winants felt otherwise: “Mr. Mellon wasn’t in the least amateurish in his many pursuits, and horses and horse sports were at the top of the list.”

THE MAN WHO HAS HELMED the team responsible for carrying a special part of the Mellons’ legacy forward since July 2016 is Sir Peter Crane, president of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, which Bunny Mellon established late in her life as a means of sharing the couple’s resources after her passing. And that legacy, says Crane, involves creating access for the public to the treasures the Mellons collected during their lives. “Our job is to benefit people,” says Crane, “and we’re charged with finding the best way to do that.”

Crane, who served as director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, knows just how special the resources that remain at Oak Spring are. “The library is full of the most incredible things, rare documents and copies of books,” he says. “These collections uniquely illuminate how our ideas have changed through time and how we ended up with the notions we have today.”

Crabapple arbor at Oak Spring Farm.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Garden walkway at Oak Spring Farm.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Bunny Mellon in her greenhouse at Oak Spring Farm.

Photo by Horst P. Horst/Condé Nast via Getty Images

The basket house at Oak Spring Farm.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

View of the apple hosue at Oak Spring Farm in Upperville.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

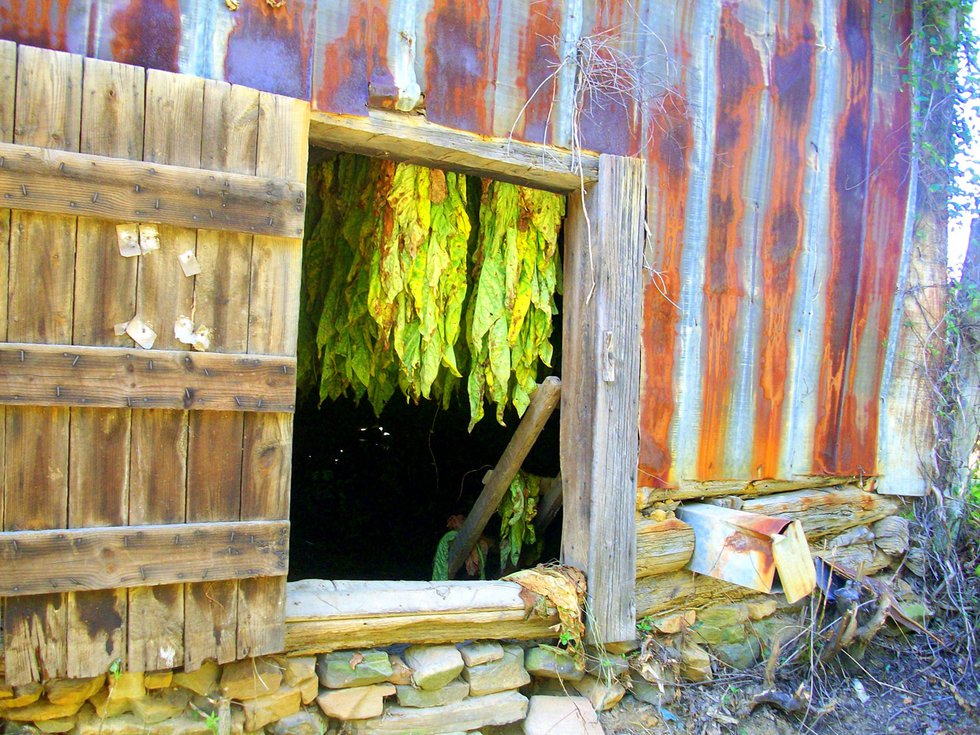

Garden equipment house at Oak Spring Farm.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Garden and grounds at Oak Spring Farm.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Garden and grounds.

Photo by Jim Morris, courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation

Crane says that part of the foundation’s mission includes hosting on-site seminars and workshops that allow participants to be surrounded by the plants, books, architecture and art that inspired Paul and Bunny Mellon. The Oak Spring Garden Library remains as it was when the Mellons were living—open to scholars and researchers by appointment. But the digital age, says Crane, may help achieve the couple’s vision of making these resources available to all people; the library’s staff is presently working to digitize many works so they will be accessible online by the end of 2017.

The fact that the Mellons’ lifetimes fell at the cusp of a digital age, preceded by a century of innovation that connected the far reaches of the world, gives their philanthropy all the more significance. Offering access to the Mellons’ gifts, says Willis, is a fitting tribute to benefactors who saw firsthand the transformative power of knowledge.

“Mrs. was born in 1910, so she got to witness the development of all these new technologies that benefitted the world, in the medical field, with computers, everything, and that really pleased her,” he says. “She always felt that she was born at the right time in history.”

This article originally appeared in our Feb. 2017 issue. For more information about the Oak Spring Garden Foundation and its programs, visit OSGF.org

Inspired By Nature

A new exhibit at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts on view beginning Feb. 10 showcases Bunny Mellon’s stunning collection of objets d’art from celebrated French-born jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger. Click here to read more.