If you don’t keep up the trades, they’ll die out

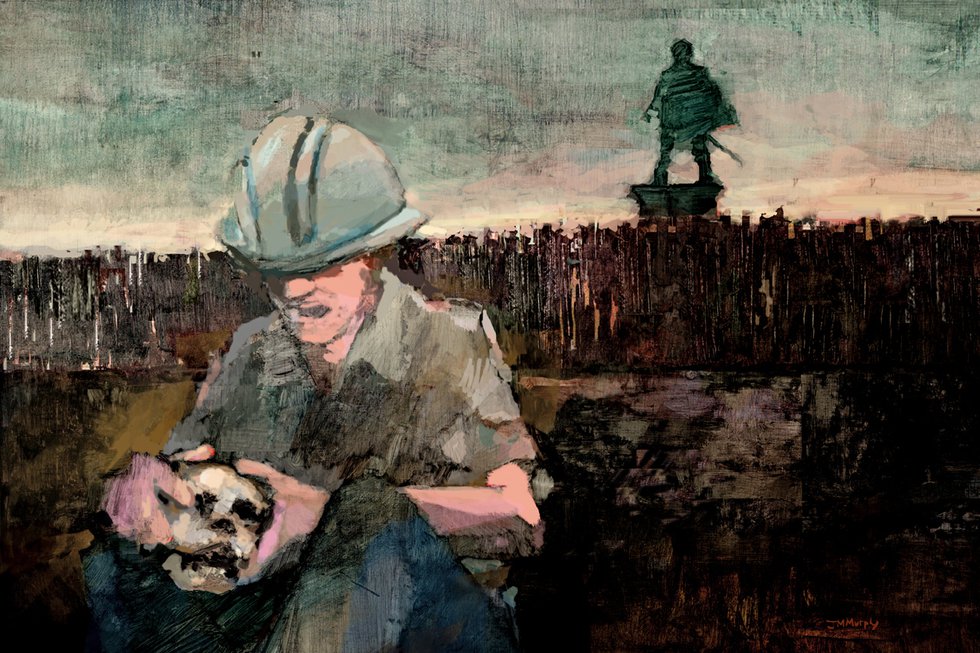

James Anderson Blacksmith and Public Armoury project – construction progress – Kitchen wall raising

(Photo courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg)

When master carpenter Garland Wood builds a house, he doesn’t plug in a drill or get the electric saw spinning. He splits his own cedar shakes and cuts the lumber using a handsaw. With this building process, using only historic tools and materials, “to build a house, you don’t need six nails from the blacksmith,” he jokes, “you need six thousand.”

At Colonial Williamsburg, the trades of the past—from carpentry to metalwork and wig making—are preserved through the Historic Trades Program (founded in 1979). Wood discovered the program “totally on a whim” during college when he entered a six-week session under the program’s founder, Roy Underhill. 40 years later, he’s still there.

In the early years, the colonial buildings were constructed more for appearances than actual use. But nowadays, Wood notes, “we rebuild something we have a specific use and purpose for.” He says they “not only practice the trade, but they put it into context—including the story of the people behind it.”

Part of the task of the Trades Program is to reconstruct the actual tools that would have been used to build the historical structures. Some of the projects Wood has worked on are the Blacksmith’s Shop, an armory, the stables behind the Peyton Randolph House, and, currently, the first black Baptist Church.

In colonial times, trades masters would pass on their knowledge to their apprentices, but as building innovations progressed, the older skills became lost. “The people who knew these construction secrets are now dead,” Wood says. Now it’s the archeologists who deconstruct building techniques from the materials uncovered.

In the 1930s, during the reconstruction of the Governor’s Palace, brick masons struggled to make the color of the bricks for the foundation match those in the original structure. “Luckily, they found some brickmakers in North Carolina and asked them to finish the job,” Garland says. “If you don’t keep up with the trade, it’ll die out,” Wood states. That’s why it’s important to keep the Trades Program going, and, thankfully, more than ten percent of the current team of a hundred or so are apprentices.

The carpenter team “does the frame, the closing of the structure, and siding,” he says, “you’ll see us making shingles and sawing the lumber.” Yet it’s illegal to build an actual 18th-century house. “Building foundations weren’t actually attached to the ground,” Wood notes. So they work with the city to make the buildings safe and accessible, while also looking as authentic as possible. “A subtle subterfuge,” Wood calls it.

The Trades Program works to inspire the “unplugged woodworking movement,” the master carpenter comments. To share more, he will be speaking at Colonial Williamsburg’s “2022 Working Wood in the 18th Century Conference,” happening January 20-23, in person and virtually. The conference will include furniture and cabinet makers, carpenter demonstrations of timber framing techniques, harpsichord-makers, and joiners providing a detailed examination of circular windows. “Sometimes,” Wood says, “the old ways are better.”

James Anderson Blacksmith and Public Armoury project – construction progress – Kitchen wall raising

Coffee House Project; Pit sawing at Great Hopes