Cannibalism is a topic that continues to fascinate.

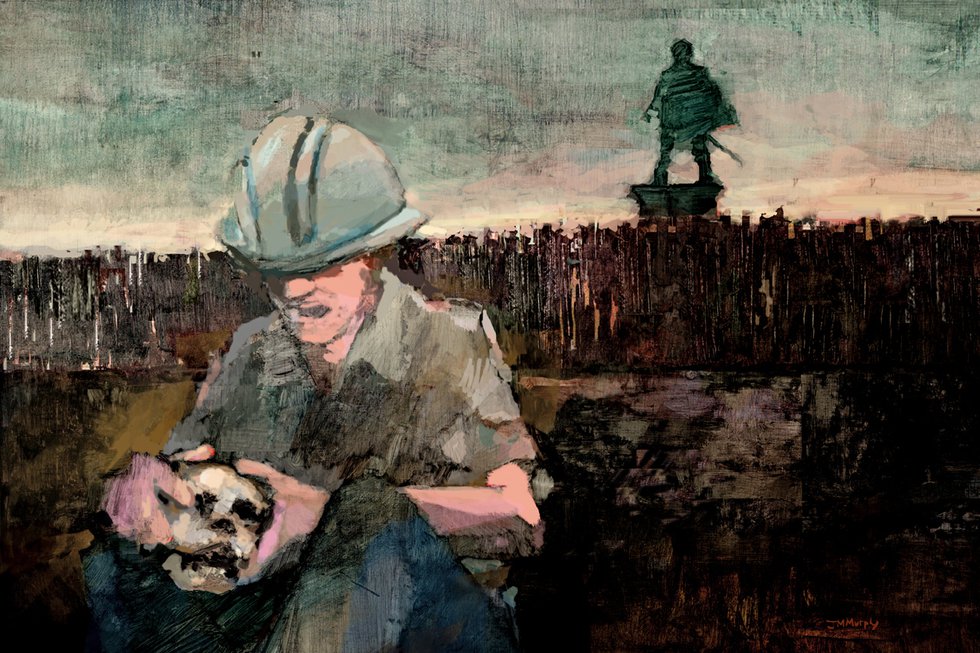

Illustration by Joseph Murphy

As you may already know, Western cultural tradition dictates that we should bury our dead, not eat them.

When anthropologists first made contact with the Wari’ tribe in Brazil, though, they learned the Wari’ were horrified at the idea of throwing loved ones in the ground to rot and be eaten by worms. Instead, they would roast and eat their kin, thus passing on the spirit of the dead into family members and, in doing so, assuaging their grief.

When Bill Schutt, author of the recently-released Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History, educated me on the no-longer-practiced Wari’ ritual, I was stunned by my initial reaction, which was basically: Hey, that’s really beautiful. That makes a lot of sense.

I had called Schutt not to be swayed on the merits of cannibalism, but rather to discuss mankind’s continuing fascination with the subject. For one, the respected zoologist’s book is a New York Times Sunday Book Review editor’s choice. Consider, too, the continuing relevance of the topic in movies and other media. The new Netflix series, Santa Clarita Diet. Hannibal Lecter. Jeffrey Dahmer. And then there was the international sensation created when, in 2013, it was announced that researchers had found definitive proof that the settlers at Jamestown had resorted to cannibalism during the horrific “Starving Time”—the winter of 1609-10.

My wife and I recently went on a group tour of the James Fort dig site led by Danny Schmidt, a senior staff archeologist with Preservation Virginia who has been researching the site since the location of the fort was first discovered in 1994. Schmidt used his inspired oratorical skills to keep the group of 40 or so fairly interested through the first part of the tour. Just as interest began to fade, though, Schmidt played the cannibalism card, showing us the pit in which the human remains were discovered.

After the Jamestown tour, my wife and I had the opportunity to eat barbecued pork sandwiches with Schmidt at the little restaurant near the dig site. As we enjoyed our meal we had a chat in which he made it clear he works hard to avoid joking about the cannibalism at Jamestown.

“I try my hardest not to slip up,” Schmidt said. “I don’t think this is something to really joke about, but I don’t want to crush people with the true darkness we are dealing with here.”

Researchers have given the unknown victim a name, Jane. They believe she was 14 and must have died only a few months after she arrived at James Fort from England in the late summer of 1609.

Schmidt did a fantastic job of describing in detail the painstaking archeology that led to this remarkable discovery. He explained too, the immense hardships experienced by those at the fort. But, he added, when he sees that “true darkness” starting to wear down his audience, “I try to lighten the mood by saying, ‘You are what you eat,’ and then saying, ‘Most of us my age and younger, unfortunately, are high-fructose corn syrup.’”

Revulsion. Fascination. Contemplation. Humor.

Add all those reactions together and you get one very hot topic. Schmidt said that a New York media firm estimated that the 2013 announcement of the Jamestown discovery reached nearly one billion people. Schmidt’s YouTube video on the topic got 250,000 views “almost immediately,” he said. The story topped Google News the day the findings were announced. Numerous documentaries and television episodes have been focused on it.

Today, the visitor’s center at Jamestown features a life-like model of Jane created by experts in forensic facial reconstruction. During that recent visit, it was clear that Jane was the star of the center. People spoke in hushed tones as if standing before a statue of Mary. As I stood there I felt sadness for her and contemplated whether or not the display is in good taste. I also felt awe for the work of the scientists and artists involved in creating the model, and disgust at those who ate her body. And I felt fear that I’d be right there with them if things ever got that bad for me.

“I think for most people it’s very poignant when they see Jane,” Schmidt said. “I’m guessing there is a natural tendency towards wondering at what point does the human condition become so tough that we have to resort to these extreme taboo actions. Folks wonder, I’m sure, if they would cross that line.” And that’s the crux of the matter. Cannibalism continues to fascinate, Schmidt said, because it is an act that forces us to imagine the extremes of human existence: “It’s the ultimate taboo in Western civilization. In Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, it’s the worst revenge imaginable. With Jeffrey Dahmer, you have the worst depravity imaginable. With Jamestown and the Donner Party and other starvation cases, you have people choosing between death and the unthinkable. Which makes you ask yourself: ‘What would I do in that situation?’”

Schutt suggested that none of us can truly know the answer unless we are actually there at the brink of starvation. Which is untrue, I told him, because I’m absolutely positive I’d eat him at the first pangs of hunger.

Schmidt answered: “It’s also a topic that brings out the most tasteless humor imaginable.”