The new Quarry Gardens at Schuyler transform this once-abandoned land into a lush habitat for native flora and fauna.

The quarry at Schuyler.

Photo by Devin Floyd

Just a few years ago, the 40-acre tract of land that now houses the Quarry Gardens at Schuyler was inaccessible, overgrown with invasive, non-native weeds and strewn with decaying rubbish. Formerly soapstone quarries that were actively mined for more than 20 years, they had been abandoned.

Today, two miles of trails lead visitors here through various terrains and plant communities. They wend across forested hillside slopes and pass through a large colony of reindeer lichen opening to vistas of sheer rock faces with their massive forms reflected in the quarry ponds. The trails also cross bridges spanning gorges and follow along a ridge with views overlooking a pretty creek called Bern’s Run.

This transformation from forgotten land to a garden that celebrates the beauty and diversity of native plants in their natural habitat is the brainchild of owners Armand and Bernice Thieblot, who ran a highly successful marketing and communications business, the North Charles Street Design Organization, in Baltimore, before turning their attention to the quarry property.

Left to right: Stinky squid, staghorn, old man of the woods, and cinnabar chanterelle.

Photos courtesy of Devin Floyd and Rachel Bush

The Thieblots purchased 440 acres of land in Schuyler on the eastern edge of Nelson County in 1991. Later, they added another 160 acres, planning to make the property their retreat from the pressures of work and city life.

Though the couple, now in their 70s, spent time over the years removing invasive plants and debris, it was not until they retired and moved to the property full-time in 2013 that the cleanup began in earnest. Since then, Armand estimates that they have hauled away 100 tons of garbage as well as truckloads of invasive plants, including autumn olive and silvergrass.

Their vision for the property came into focus while on a cross-country road trip. “We visited Butchart Gardens on Victoria Island near Vancouver, British Columbia,” says Bernice, “and that’s where we got our idea.”

Butchart Gardens was conceived and created by Jennie Butchart in the early 20th century. Butchart was inspired to establish gardens on the land of her family’s exhausted limestone quarry. To begin, she had tons of topsoil from local farms hauled to the site by horse and cart. At the base of the quarry she created a sunken garden. Over the years she transformed the stripped, bare land into a series of themed garden rooms that today attract more than 1 million visitors each year.

The Thieblots discussed the idea of transforming the quarries on their land into a garden during the long hours driving back home. But instead of creating a mass-planted display garden similar to Butchart Gardens, the Thieblots wanted to celebrate indigenous flora and fauna as well as the quarrying history of their land.

Morels and southern wood violets.

Photos by Devin Floyd

American lady butterfly.

Hairy skullcap.

American monarch and local thistle.

The Thieblots approached their new project mindfully. Once home, they identified 40 acres of their property for the garden and set aside 400 adjoining acres in the state’s conservation easement program, thus creating a permanent buffer from development and protecting the viewshed. For the master plan, they hired Charlottesville-based Land Planning and Design Associates (LPDA), a firm specializing in landscape architecture and land planning.

LPDA created a map outlining trails and roads to circumnavigate the two quarry pools, viewing spots for overlooks and a parking area, and proposed repurposing an existing Quonset hut into a visitors’ center.

The native geology of the quarry played an important role in the planning. In its heyday, Schuyler was the center of the world’s most productive soapstone vein that supported 50 active quarries in Nelson County. From 1880 until 1975, the Alberene Soapstone Company was headquartered in Schuyler, where they quarried the dense, soft grey stone. Six of these quarries are on the Thieblot’s land.

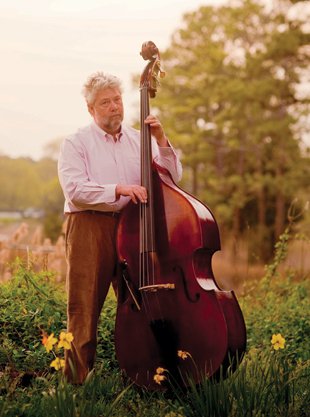

Devin Floyd recording species for the site survey that preceded garden planning.

Photo by Rachel Bush

“The soapstone makes the soil pH alkaline, which is not typical of the Piedmont,” says Dorothy Tompkins, a retired physician who has served as president of both the Piedmont Master Gardeners and Rivanna Master Naturalists, and is currently president of the board of the McIntire Botanical Garden in Charlottesville. “With slightly alkaline soil and the plant communities it fosters, the Schuyler Quarry Garden is the premier native plant garden in our area,” she adds.

Realizing they had an unusual growing environment on land that also has a fascinating industrial history, the Thieblots wanted to celebrate both. To begin, they hired Devin Floyd, a geologist, naturalist and archaeologist who is a founder of Charlottesville’s Center for Urban Habitats to conduct a survey of the existing biota. Floyd began cataloging the flora and fauna of the land with the help of his partner Rachel Bush. They completed their first survey in May 2015 and a second in 2016.

The resulting 143-page document catalogs 525 plant species, including three different species of ladies’ tresses orchids; morel mushrooms and arrowleaf violets; 47 different trees; and 157 different fauna. Among the rare fauna are the smooth green snake; the gray petaltail dragonfly, which often indicates the presence of skunk cabbage and ferns; and the juniper hairstreak butterfly.

With the information gleaned from the survey, the team divided the land into 14 ecozones and seven conservation zones. In the ecozones, they used “indicator” plants to determine what can grow in those areas. To enrich these ecozones, the Thieblots’ team is propagating and planting more of the indigenous flora as well as adding other native genera and species that will thrive in those soil and microclimate conditions.

Bernice and Armand Thieblot

In the conservation zones, no new genera are being added. Instead, the focus is on building out the existing plant communities. Some of these plants are local genotypes so specific to this land they have yet to be positively identified.

To prepare for their public opening in April, the Thieblots and their team of seven paid staff and a small volunteer contingent conducted a massive fall planting of 28,000 plugs and small plants—about 1,000 per day, according to Bernice. They also planted 78 large-sized native trees and shrubs, placing them to mark the trails and to provide structure and screening in the gardens. Last winter, the Wintergreen Nature Foundation and the Center for Urban Habitats Nursery grew plants from seed collected on the Thieblot’s land. Soon these seedlings also will populate the gardens.

To date, the Thieblots have funded the project out of their own pockets. They plan to eventually raise additional sources of capital through donations and by offering memberships.

Visitors who walk the trails will find 35 “galleries” of native plant communities set amid the natural landscape. A map of the garden marks the gallery locations.

In the visitors’ center, where there is a classroom with a giant projection screen (“for 8-foot butterflies,” quips Bernice), there is a computer available for those who want to look up detailed plant information.

To celebrate the history of the region, the visitors’ center will also feature a model of the historic Nelson and Albemarle Railroad, which transported the soapstone to market. In the three short years the Thieblots have been working on the project, they have accomplished remarkable things. And this is just the beginning. QuarryGardensAtSchuyler.org

This article originally appeared in our April 2017 issue.