Once upon a day, hot and eerie,

while I wandered, weak and weary,I pondered not a bust or lore,

but Poe the man—was there more?

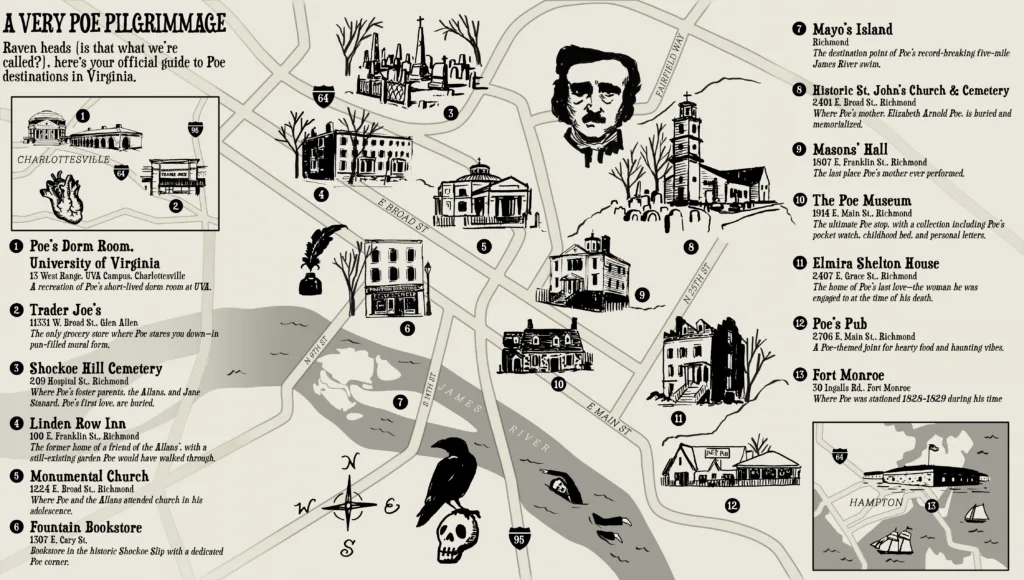

Cobblestoned streets serve more than just aesthetics in a city like Richmond. Rather, they lend themselves to lore and legend. We begin to wonder, indulging in a rare kind of enrichment: Whose footsteps echo here? And pause, a second. Well, my myth-minded meanderers, look no further than 1914 E. Main St. for your fittingly romantic answers.

A Fountain and a Shrine

Behind a simple wrought iron fence and wrapped in aged stone walls, lies the Poe Museum—home to the largest continuous collection of Edgar Allan Poe artifacts in the world. And for the ever-revered poet, the virtuoso of versification, the master of the macabre—what could be a more fitting beginning to his eponymous museum than, why, a shrine?

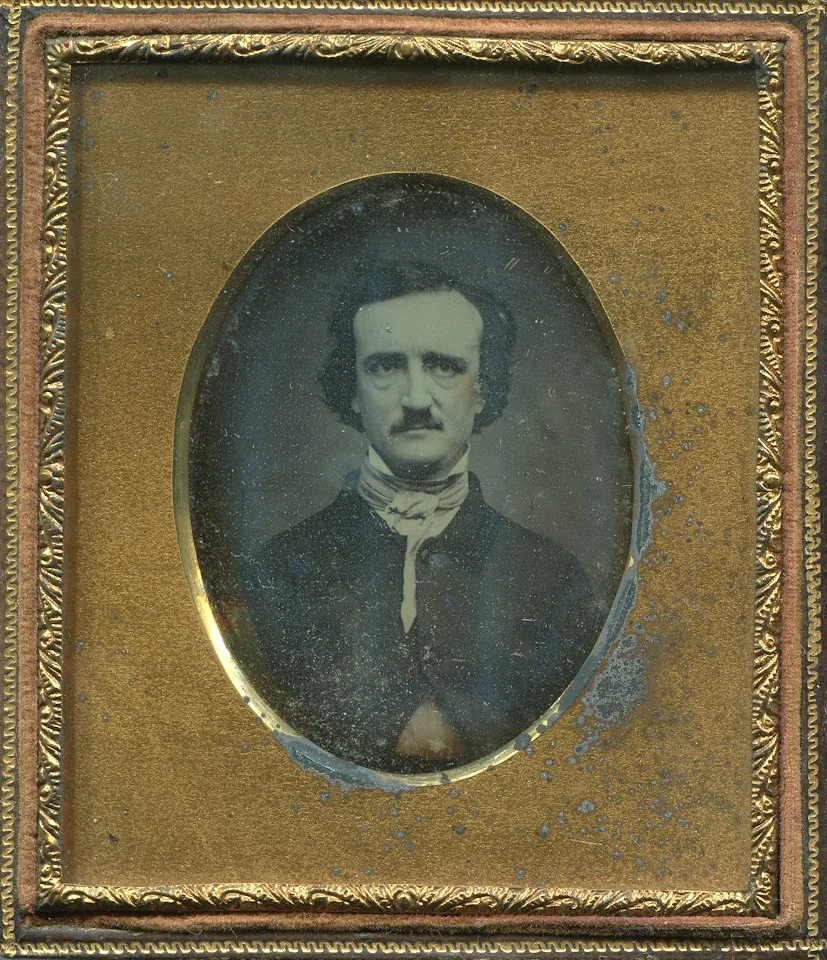

The Poe Shrine arrived on Richmond’s scene in 1922 as the northern bookend to a memorial garden aptly named the Enchanted Garden, complete with the flowers and fountain Poe describes in his poem of the same name. That same year, the museum sprang up in the surrounding buildings. The shrine holds a still-standing bust of Poe and offerings from loyal visitors. Between it and the Old Stone House at the garden’s far end—the oldest surviving residence in Richmond, built in the late 1600s—the setting was inevitably atmospheric, its aura already an ode to the great poet, before many letters, clothing, daguerreotypes, paintings, and manuscripts arrived.

Upon learning of a Poe museum in Richmond’s Shockoe Bottom, the usual responses are: I have to go!; Poe … the heart under the floorboard guy?; or Why here? Wasn’t he from up north?

From Out That Shadow

Edgar Poe was indeed born in Boston in 1809 to two actor parents who died during his infancy. (And yes, he’s the one who wrote “The Tell-Tale Heart,” where a corpse’s heart thunders from under the floorboards.) Before her death from tuberculosis, his mother, Elizabeth Arnold Poe, had moved with her children to Richmond and performed a final time at Masons’ Hall—the last stage she would ever grace. Newspaper accounts of her illness prompted a wealthy, childless socialite named Frances Allan to care for her and eventually take in her orphaned son. Thus Poe gained a home in Richmond—and the “Allan” in his name.

In the Allans’ aristocratic household, Poe suffered a contentious relationship with his foster father, John Allan, and all the woes of a lovesick boy—falling for several schoolgirls. (He was known to reuse the same love poem for each, swapping only the name.)

Though Richmond can’t claim Poe’s birth, it can claim his coming of age.

“Virginia completely shaped who he was as a writer,” says Maeve Jones, Poe Museum executive director. “There’s his love of nature. He loved the James River—he was a swimmer. He started writing for his classmates. He fell in love for the first time here. I really do think he became who he was while living here.”

Baltimore-based David Keltz, a Poe reenactor for more than 30 years, has performed one-man shows at the Poe Museum on numerous occasions.

“Richmond’s audiences are extremely enthusiastic—especially when they know that Poe was a Virginian,” Keltz says.

And Virginian he was, through and through—raised, shaped, and very much alive here. As a teenager, Poe swam five miles against the tide in the James River—a record that still stands. A true Richmonder badge of merit.

Yet Poe was famously a struggling writer, a contrast to the wealth surrounding him in childhood—a result of his rocky relationship with John Allan, who sent him to the University of Virginia without enough money to live on, then later pulled him out. Of his time at UVA, Poe wrote, “It was my crime to have no one on Earth who cared for me, or loved me.” Not quite the Wahoo-on-the-Lawn experience.

He briefly pursued military training, but never reconciled with Allan and was ultimately cut off entirely. Campbell Harmon, a Connecticut-based Poe reenactor, sees this break as central to Poe’s identity.

“For the rest of his life, he saw himself as a displaced Southern aristocrat,” Harmon says. “You see that reflected over and over again in his writings—characters on the outside of society, cut off from inheritances. That’s in “The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Purloined Letter” .… You cannot overstate the importance of his time in Virginia.”

The Mask Which Concealed the Visage

From the ashes of a tragic life came the winged glory of a rare writing sensation. Amid money troubles and lovers’ woes, Poe’s pen was his constant companion. Through it, he conveyed horror, of course, but also humor and love. Many consider him the first truly successful career writer in the U.S. Bouncing across the states between newspapers, magazines, and standalones, Poe became, in short, a hit.

“He was the toast of every home he entered,” says Harmon. “He was in demand as this romantic poet who could charm everyone around him. He was a star—an international star, before that was even a thing. He was a media star.”

Described this way, Poe sounds more like a social media influencer than a brooding writer. But the consensus among reenactors, curators, and amateur historians is clear: Poe was social, casually charismatic, frequently charming—and, crucially, funny.

“What I often see is people conflating Poe with his narrators,” Jones explains. “The Poe we put on bobbleheads, or tattoo on ourselves, is this morose, sickly-looking man—a tortured poet. And in many ways, he was. He spent a lot of time thinking about hardship, the macabre, the psyche, and madness.”

But he also wrote stories like “The Spectacles,” in which a vain young man refuses to wear glasses and accidentally marries his great-great-grandmother. Upon finally seeing her clearly, he cries, “What, in the name of everything hideous, did this mean?”

“The Spectacles” is one of Keltz’s favorites—it’s one of the few audiences immediately recognize as a comedy. Others, like “Never Bet the Devil Your Head”—where the narrator is decapitated (“what might be termed a serious injury,” Poe writes) and later eaten by dogs—may take a moment to land.

“He wasn’t just this solitary, pining figure,” Jones says. “He was engaged, active, and people were drawn to him when he was thriving.”

A Love That Was More Than Love

Primary among Poe’s more lively interests was romance. He famously wrote “To Helen” for his childhood best friend’s mother, who died of tuberculosis and was buried at Shockoe Hill Cemetery, where Poe would go to mourn.

“Aldous Huxley once called ‘To Helen’ vulgar—like ‘a diamond ring on every finger,’” Keltz says. “Poe might’ve found it amusing that his poetry was accused of being too beautiful.”

Other muses inspired some of the most striking love poetry ever written. “Annabel Lee,” with its desperate devotion—“Nor the demons down under the sea / Can ever dissever my soul from the soul / Of the beautiful Annabel Lee”—still resonates. One older visitor to the Poe Museum bought a collected works edition for his wife and inscribed it, “To my Annabel Lee.”

“It just reminded me that, as gothic and macabre as Poe can be, he was also a true romantic,” Jones says.

Yes, he did marry his cousin—Virginia Clemm, his only wife. “First cousin marriages were common then,” Harmon explains, “but her age—that was unusual, even for the time.”

Clemm was 13 when she married 27-year-old Poe; their documents were falsified to list her as 16. “Whether it was a romantic relationship, or more of a sibling-like, filial affection, is something a lot of people debate,” Jones says.

There were practical reasons, too—Clemm’s widowed mother couldn’t work, leaving them poor and vulnerable. But married life wasn’t bliss: Clemm remained sick and destitute through much of their time together, dying at just 24.

“On the one hand, Poe was a creative genius,” Jones says. “On the other hand, he struggled deeply—with substance abuse, with money—and may not have been the most attentive or supportive husband to Virginia that he could’ve, or should’ve, been. Holding those complexities in one historic figure can be tricky, especially for guests who really revere Poe. But I think that’s one of the valuable things about being a museum: We can encourage people to think more flexibly and critically about historical figures.”

Moldavia the house that Poe lived on 5th and Main Street in Richmond with his foster parents John and Frances Allan.

Man’s Real Life

And so, as I wander the time-weathered bricks of the Poe Museum’s pathways, I imagine him walking here, 200 years ago. Poe once stood guard outside this very house in 1824, when Lafayette visited Richmond—part of his junior honor guard duties.

I find a black cat in my path. It’s Tib, one of the museum’s resident cats—a hallmark here since a litter was discovered behind Poe’s shrine in 2012.

Poe, a lifelong cat lover, had a childhood pet named Tib. His later cat, Catterina, was so devoted that some believe she died the same day he did. There are accounts of Clemm sitting beside Poe at work, their cat often curled in her lap. It’s easy to imagine her gently keeping curious paws at bay as he wrote, preventing tiny paw-shaped ink stains. The bell on Tib’s collar jingles as he leans into my offered scratches.

A garden, a black cat, and a bell—each a living, breathing line of poetry. And suddenly I see Poe’s “Enchanted Garden,” “The Black Cat,” “The Bells,” and endless other tales unfurl before me in striking salience. I can see myself pull up a seat at a desk, imagine tales both strange and wonderful, these memories fresh in my mind. And for a brief moment, I can see Poe as he really might have been: a writer, with an idea—and a city full of more to chase.

The enchanted garden and Poe Shrine at the Poe Museum

This article originally appeared in the October 2025 issue.