My introduction to carpenter bees came via a mysterious drift of sawdust on our deck. Stooping down to examine the underside of the railing, I found a perfectly round, finger-sized hole drilled neatly into the wood. When another tiny mound of sawdust appeared, then a third, I did as one does when faced with a question: I went straight to Google. And thus I discovered that what I’d taken to be a handful of bumblebees drifting lazily above the deck were in fact their close lookalikes—carpenter bees.

As their given name implies, and the holes in our deck railing confirm, these bees are woodworkers. Unfortunately, if you have carpenter bees, the work they’re actually doing around your house probably isn’t going to thrill you. They dig a bee-sized hole into the wood, then excavate a tunnel parallel to the surface that can extend, over time, as far as a foot in length—and sometimes even further, because successive generations of bees may reuse the same tunnel.

Regardless of how you feel about bees chewing their way through your woodwork, it’s an undeniably impressive feat of labor. Once the tunnel is excavated, female carpenter bees lay their eggs in individual chambers, each egg accompanied by a ball of pollen that will feed her offspring. Each of these chambers, in turn, is walled off with wood pulp as she works her way backward toward the entrance. When the young bees emerge over the summer, they will continue to feed on flowering plants before returning to the shelter of tunnels to overwinter.

It is because of this tunneling behavior, of course, that people tend to regard carpenter bees as troublesome pests. Yet that perspective fails to take into account the benefits they offer us. Carpenter bees are generalist pollinators, which means they play an important role in a thriving, healthy ecosystem—and in our blooming gardens.

James Wilson is an assistant professor and the extension apiculturist (that’s “bee guy” to us lay people) in the Virginia Tech Department of Entomology. Carpenter bees, he explains, are “buzz pollinators,” or, in technical terms, use a process called “sonication” to shake pollen loose from a plant. “It’s like your fancy electric toothbrush,” says Wilson. “They can vibrate their wing muscles without vibrating their wings, causing pollen to be released.”

Are you a fan of luscious summer tomatoes plucked ripe and warm from the garden? Well, you might be interested to know that tomatoes are among a variety of plants, including blueberries and eggplants, that “can’t be pollinated without sonication,” Wilson says. And honeybees, he adds, don’t use sonication.

Also, you would really have to go out of your way to get stung by a carpenter bee. The males can’t sting at all, and the females can barely be bothered. “I have never been stung by a carpenter bee, and not for lack of trying,” says Wilson.

Nevertheless, when they find they have carpenter bees, “A lot of people go on the offensive,” says Wilson. So yeah, you can try camouflaging with paint, to make your wood look less like wood. Several websites suggest offering alternative nesting sites; carpenter bees like soft, untreated, weathered wood. There are carpenter bee traps too, though Wilson says “they are likely killing a lot of bees but not doing much to protect home structures.”

You can also, of course, bring out the big guns—pesticides and exterminators. But be warned that your efforts may not equal the desired results. Controlling carpenter bees is “difficult (or nearly impossible),” a North Carolina State Extension publication (aptly called Insect Notes) cheerily advises, adding “impractical,” “unsafe,” and “a time-consuming and seemingly endless task,” to boot.

Reassuringly, the NC State Extension publication also notes that “typically, carpenter bees do not cause serious structural damage to wood unless large numbers of bees are drilling many tunnels over successive years.”

So maybe it’s happier to coexist. “We would not want to eliminate the carpenter bees in the world,” says Wilson. “Generalist pollinators pollinate a wider variety of plants so they have a larger impact.”

After all, from a bee’s perspective, “we are invading their world with our own built structures,” Wilson points out. They build their nests in wood, and “we just happen to have built our entire lives around wood.” It’s like putting up a beautiful neighborhood and being surprised when people want to move there.

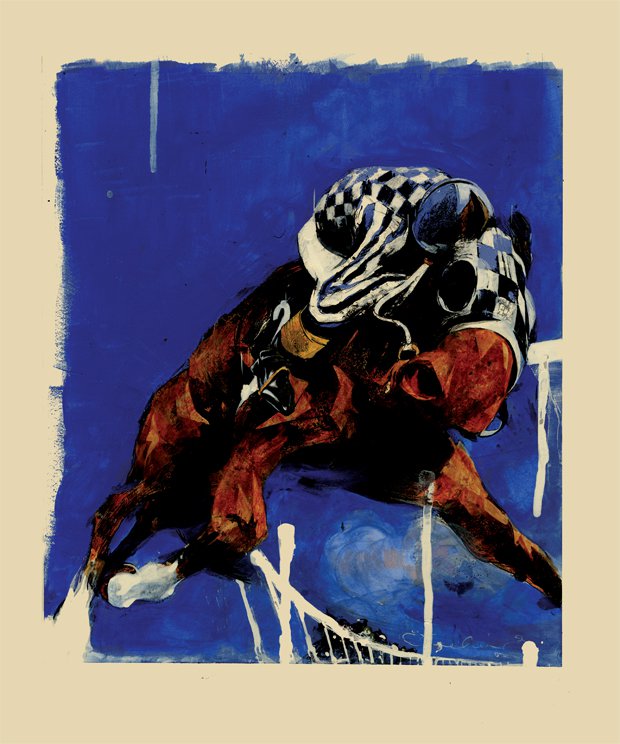

Featured illustration by A. Richard Allen. This article originally appeared in the April 2025 issue.