A Mathews woman challenges her kids to give up TV for a year, and they’re all the richer for it.

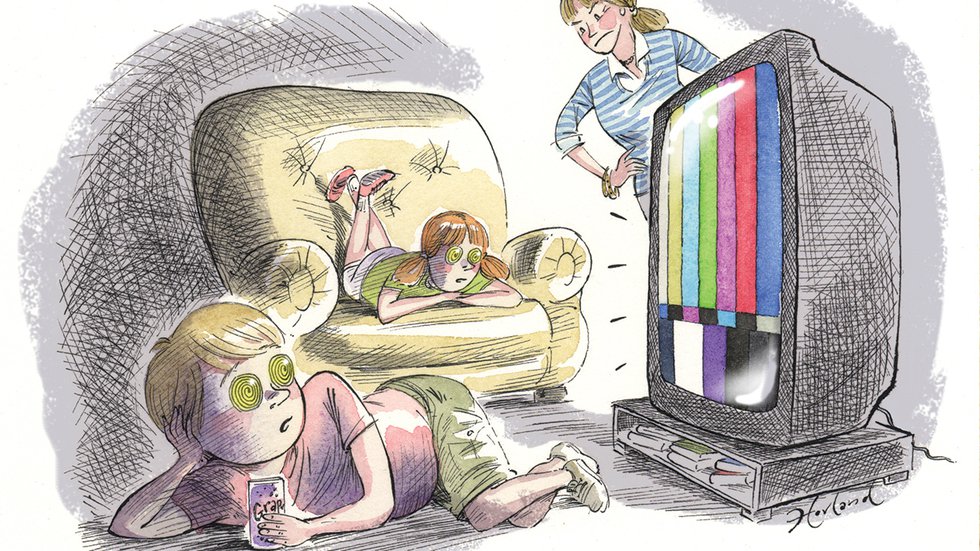

Illustration by Gary Hovland

In July 1990, Carol Hudgins offered her children, Steve and Angela, a modest proposal: No TV (including videos!) for one year. This is the generation, remember, that could sit and watch Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, The Princess Bride, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles again and again on video cassette. And again. You’d think the Hudgins kids’ response would have shattered windows across Mathews County, but no. They said yes. She had offered a little incentive, you see: a $100 reward for each. Not only did the kids know a good thing when they saw one, they made some interesting, non-electronic discoveries along the way and a year later snagged the C-notes.

Carol probably took the words out of many a parental mouth when she told the Gloucester-Mathews Gazette-Journal that “too much time was being spent in front of the TV.” On Saturday mornings, for example, it was “nothing but TV” from 7 a.m. till noon, nonstop, “whether or not they were interested in what was on.” The simple, passive absorption of the output of the tube was alarming (tube, because it was 1991). But Carol devised what turned out to be a brilliant plan, presenting Angela, then 9, and Steve, 8, with a one-year contract in which they agreed to avoid TV except for educational shows, which Carol had to approve. Once signed, the contract went to that kiosk of things official in every American home, the refrigerator.

What would the kids do, wondered Carol and husband Charles, who, despite their televisual concerns, themselves “watched some TV after 9 p.m.” Well, they would take to the challenge like a fish to water, literally in a couple of cases, taking swimming lessons at 4-H camp and learning to crab using bait and string on Winter Harbor, at their own backyard.

Steve’s friends were aghast, wondering how he could even think of such a thing, saying “It’d kill me!” Angela heard, “How can you stand it?” Despite missing a few cartoons, they done good, taking advantage of low-tech, high-touch entertainments—books for one. They became readers, using the library, where they took part in the summer reading program. “We have a lot of books at home,” said Angela of their “frequent diversion with the written word,” ran the story, and that surely gave them an important edge in the reading habit.

What would Mama allow? Some shows fit right in with the children’s intellectual and outdoor pursuits: NOVA, Nature, and National Geographic specials were regular fare. On the entertainment side, there was Lawrence Welk. Ah-ONE and ah-TWO? Ah, no. Steve and Angela would “usually fall asleep” during the PBS staple rerun. Also, during sleepovers away, they could watch TV with their friends. At home, “if their own disbelieving company couldn’t do without a show, the television screen at the Hudgins household could once again be lighted,” reported the Gazette-Journal. These events were surely timed with Welk to induce them to turn in.

The first year ended, Carol Hudgins fulfilled her side of the bargain, and Angela and Steve were each a hun richer. What did they do with their proceeds? Well, they saved it and negotiated for a one-year renewal of the contract, same terms. Their affinity for water had given them ambitions. In another year, presuming they won, they wanted to put their $400 in no-TV rewards toward the purchase of a paddleboat.

In talking to the Gazette-Journal about the television fast, Carol said she wanted to “show other parents their kids really can do without it.” And that is a noble, if optimistic view. Hindsight shows just how optimistic: About five years later there came the World Wide Web to drain brains, and that has proved a heftier challenge.

WWI Sub Wonder – 1916

A German “under-sea boat” has reached U.S. shores, and Benjamin Fisher, editor of Eastville’s Eastern Shore Herald, heralds that it “compels the admiration of every man who loves true grit,” be he anti- or pro-German. Though the German-American press slams our government for “sympathies to the Allies,” when a submarine arrives laden with a “mercantile cargo,” it’s given “the same treatment accorded like vessels of other nations,” holds forth the editor. Nevertheless, he allows, “a great majority of our people are in sympathy with the Allies.” And the sub’s effect on the war “no one can foretell.” There are, at this point, no rocket scientists on the Eastern Shore.

Mailbox Intensive Care- 1941

Chathamites think Rural Mail Box Improvement Week will never get here, but get here it does! To spread the good cheer, Postmaster J.J. Patterson and two of his rural mail carriers converge, post-improvement, at the mailbox of W.C. Falls for a photo op. Following repairs and shorings-up, the nearly 1,200 such boxes (mailboxes are considered federal property by law) on Chatham mail routes are now “in good shape,” pronounce postal officials to the Pittsylvania Tribune following the May 5–10 mailbox-fixing spree. An inset picture shows the Falls’ box before, in a pitiful state indeed, barely hanging on.

Cop Dog Gets Nod – 1966

Staunton City Manager C.M. Moyer Jr. finds himself in a quandary in presenting Blitz, a German shepherd and half of the city police’s Canine Corps, a medal for “outstanding service”: there’s nowhere to pin it. The Friday before, Blitz and Officer Donald Johnson, his trainer, are summoned to a murder scene in pursuit of suspect John Wayland, of whom there’s nary a sign, but “[o]ne whiff of Wayland’s hat, and Blitz was off,” reports the Staunton Leader. In brief, Wayland glimpses the beast and surrenders. “A real professional job,” a witness rules Blitz’s work. “Their action reflected credit on the team of man and dog, now accepted as an integral part of the Staunton Police Department,” Moyer says. Doggone right! Oh, Johnson receives an award too.