It was not a dark nor stormy night when one legendary great man met his tragically grim fate. In fact, it was a pleasant, remarkably normal spring morning in 1806. George Wythe—esteemed lawyer, professor, judge, and revolutionary leader—sat down for breakfast at his Richmond home with his cook Lydia Broadnax, a promising black student under his care named Michael Brown, and his 17-year-old grandnephew George Wythe Sweeney.

Sweeney sulked by the fire, as teenagers are wont to do. Broadnax saw him toss wrinkled papers into the flames and thought nothing of it as she served what historians later called a “frugal breakfast.” The exact contents are lost to time—except for the coffee, which Sweeney had hunched over moments earlier.

That coffee pot, on that all-too-ordinary day, would deliver one of Virginia’s most beloved Founding Fathers a most cruel end.

Broadnax, Brown, and Wythe all drank from it. Within a day, they were—as George Wythe reenactor Robert Weathers puts it—“purging from both ends. Excuse the phrase.”

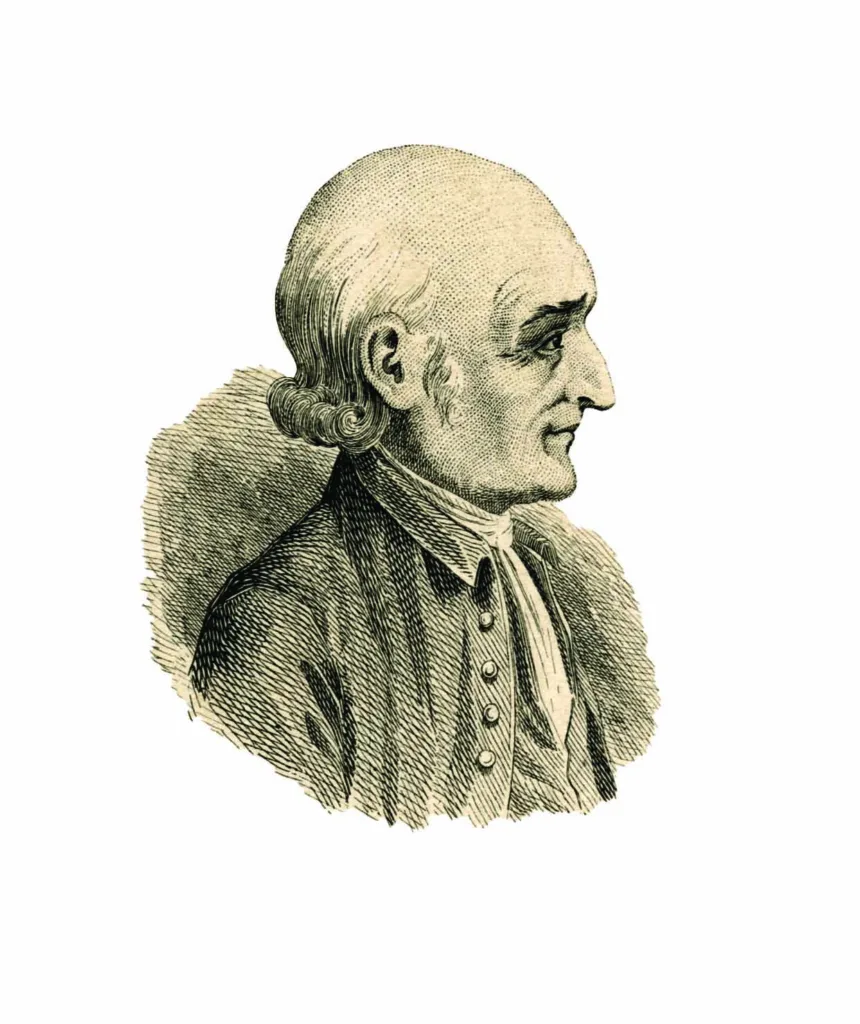

When Weathers started as a historical reenactor at Colonial Williamsburg in 2008, Wythe was just another curly-wigged Colonial figure to him. Six years into portraying him, he can’t believe CW ever considered skipping a Wythe interpreter.

“My elevator pitch for George Wythe is this: When he died in 1806, the President of the United States, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, the Attorney General of the United States, the Attorney General of Virginia, the President of the College of William & Mary, two U.S. Senators, and multiple other Virginia officials were all students of George Wythe. His influence touches every name you know and every name you don’t.”

Wythe was instrumental in shaping America and legal education at William & Mary. An early abolitionist, he freed slaves both from the bench and in his own household, including Broadnax. Weathers likens Wythe’s unanimous appeal to just one modern icon: Dolly Parton. “In addition to being this intellectual and political titan, he was also just a swell guy who we all love.”

Wythe moved from Williamsburg to Richmond in his 60s, still working and tutoring young Michael Brown. For more than 50 years, Wythe had been practicing law, teaching it (to the likes of Jefferson, Marshall, and Monroe), and living by it.

And yet, in death, it was the law that failed him.

Wythe lingered for two weeks after that breakfast—sick, bed-bound, and alert enough to see Brown die, to learn that Sweeney, his own grandnephew, had forged checks from his account, and to write him out of his will. Sweeney had money troubles, likely gambling-related. His attempts to sell rare books from Wythe’s library hadn’t been fruitful

enough, so he forged checks—eventually deciding to “shuffle the old man along,” in Weathers’ words, knowing he stood to inherit the bulk of Wythe’s estate.

On June 8, 1806, Wythe died at roughly 80 (his exact birth year lost to history). He told his bedside vigil-keepers to “cut” him: an autopsy request. He knew who had done it.

The autopsy suggested arsenic poisoning, but not definitively. Still, there was evidence aplenty. Servants saw Sweeney chopping something in Wythe’s workshop, staining an axe yellow (a telltale shade of arsenic). Arsenic was found in a packet outside Sweeney’s jail cell. Most damning of all? Lydia Broadnax. She’d survived the illness, seen Sweeney rummage through Wythe’s desk in the days prior to Wythe’s demise, and watched him handle the coffee pot.

William Munford, one of Wythe’s last students, boils it down to this: “It may be said, indeed, that in one deplorable instance .… [Wythe’s] benevolence was placed on an unworthy subject, and repaid with black ingratitude.”

Sweeney was arrested and tried for the crime, but the jury acquitted him. In Virginia at the time, black people could not testify against white defendants. And so, Sweeney walked free, fled to Tennessee, and disappeared into history.

Broadnax, for her part, went on to become one of only 50 black property owners among the roughly 6,000 black residents in Richmond at the time of her death.

Wythe’s story doesn’t end here. His legacy lives on in American law—and in person, thanks to Weathers at CW, who performs in Wythe’s actual house, just beside the Governor’s Palace.

Those more intrigued by the mystery than the man can visit the reported site of the crime: the southeast corner of Fifth and Grace streets in Richmond—now home to the Secret Sandwich Society. Perhaps the real secret was this sordid story all along.

This article originally appeared in the October 2025 issue.