The marriage didn’t start on a high note.

The bride, 15-year-old Mary, cried through the ceremony, hardly swept off her feet by the groom, her first cousin William. Introduced a few days earlier, she’d been weeping ever since. Her betrothed, chosen for political reasons, was 12 years her senior, four inches shorter, and hunchbacked, with blackened teeth and a pockmarked face. His command of English was poor, and, on top of that, he smelled bad.

“It was a bit awkward at the beginning,” said historian Phillip Emanuel, who studied at William & Mary.

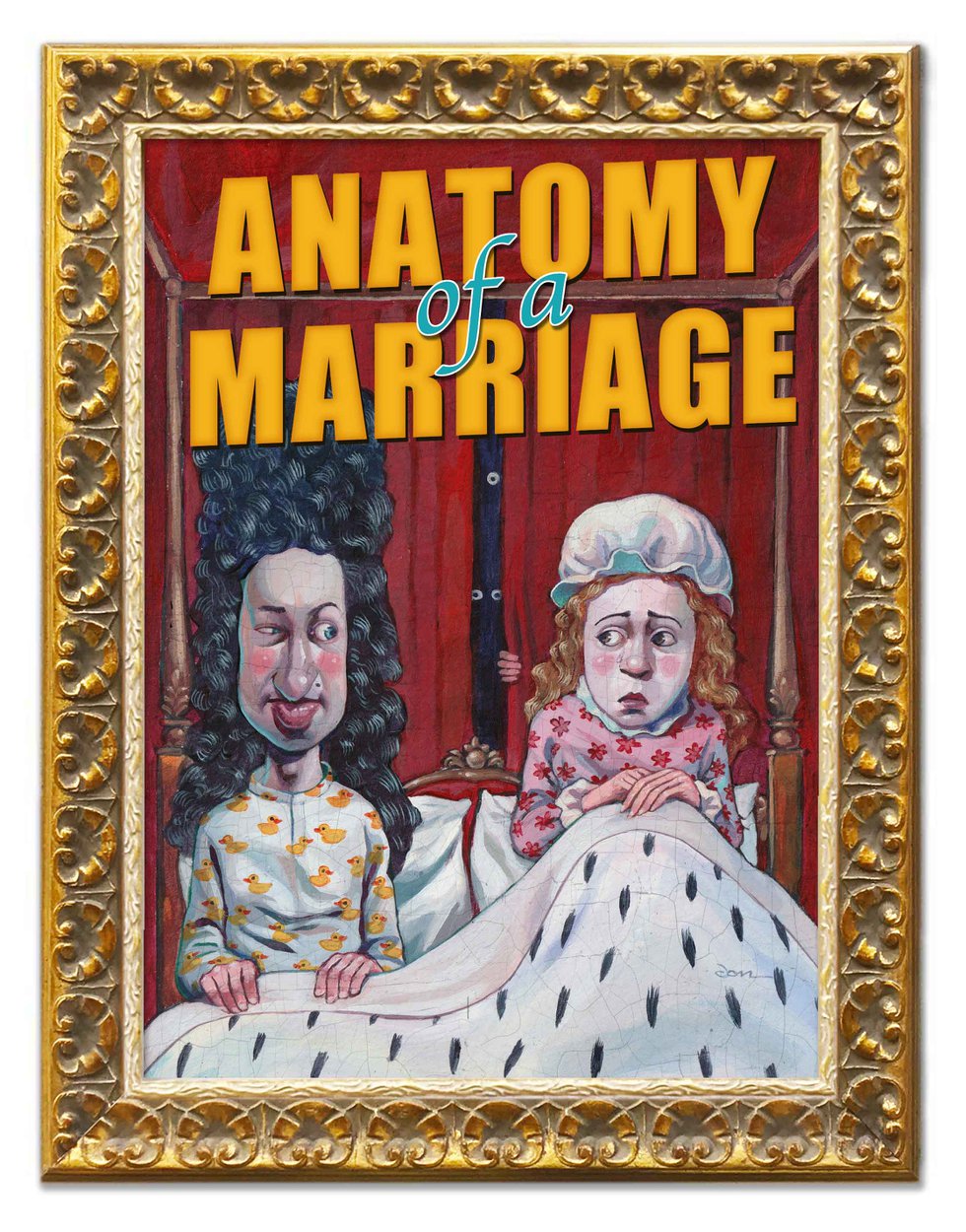

Given all that, we shouldn’t be surprised that the future King William III and Queen Mary II’s wedding night was hardly a wild booty call. The royal family—never a group with a good grasp of boundaries—joined the couple in their chamber for a bedding ceremony, a wedding tradition that thankfully has gone out of style.

Even after Mary’s uncle, King Charles II, pulled the bed curtains to give the couple a modicum of privacy, sparks didn’t fly. William refused to remove his woolen underwear, saying Mary would have to learn to accept him as he was.

Although the future queen was a beauty, there was something William found more attractive than her shapely figure: her birthright. Mary was second in line to the throne, and William knew that if he played his cards right, he could end up as king.

It might sound like the premise for a bad reality dating show, but this couple’s influence on Virginia is still felt today. They founded the College of William & Mary, and not only was Williamsburg named for the king but so were two Virginia counties.

Today, though, they’re hardly celebrated. Even the college pays little attention. You have to work your way to the back entrance of Tucker Hall to find King and Queen Gate, where solemn statues of the monarchs stand atop brick pillars. But look carefully. More prominent than the founders are the “Do Not Enter” traffic signs posted beneath them.

Mary Miley Theobald, a history writer and William & Mary grad, says she’s not surprised that her alma mater doesn’t go all out for the couple who signed the school’s founding charter.

“Neither ever set foot on the campus. Queen Mary died shortly after the school was chartered, and I don’t think King William gave the place another thought,” she said. The school had been created to train Anglican priests and convert Indians to Christianity, two issues which concerned Mary.

“After the Revolution, I’m a little surprised they didn’t change the name, but then, Virginia didn’t do any of that,” Theobald added.

What’s most astonishing is that this seemingly destined-for-divorce pair eventually became the model for a modern marriage and jointly ran the country. They brought wise rule to England, recognizing the role of parliament, and accepting a bill of rights.

“Their reign is incredibly significant for many things,” said Emanuel, now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania. “But even then, if you ask the average Brit who William and Mary were, they probably couldn’t tell you.”

The couple took a while to warm up to each other. Within days of their 1677 marriage, William dragged his wife back to his native Holland, where Mary first sulked, and then spent her time designing gardens and studying her Anglican faith. Meanwhile, William took Mary’s childhood friend as a mistress.

But when a royal crisis a decade later forced her to take sides, Mary backed her husband over her father, who faced bitter opposition because he was Catholic. The couple assumed the throne under an unusual power-sharing agreement. Mary was named queen, but William refused the traditional title of queen’s consort and insisted that he be named king. A deal was struck, and they both took power.

“William spent most of his reign abroad, fighting the French each summer, and she ran Britain when he went off,” Emanuel said.

After years of struggle, the pair eventually settled into a comfortable partnership. When they weren’t attending to affairs of state, they doted on their pet pugs, and, like a modern couple, planned home renovations—in their case, remaking Hampton Court and Kensington Palace.

And even if it was never a smoldering passion, the royals did develop a deep affection.

Theobald points to a letter Mary wrote when William was off on a military campaign. “I am not able to think of anything else, but that I love you in more abundance than my own life.”

Not bad for a marriage that started in tears.

Larry Bleiberg is a past president of the Society of American Travel Writers. The former travel editor of Coastal Living magazine and The Dallas Morning News, he contributes to BBC Travel, The Washington Post, and many others. He lives in Charlottesville.