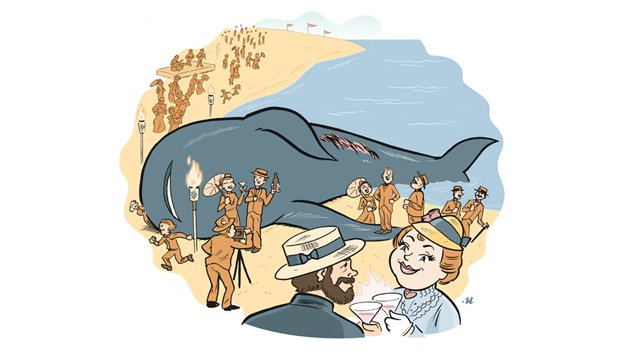

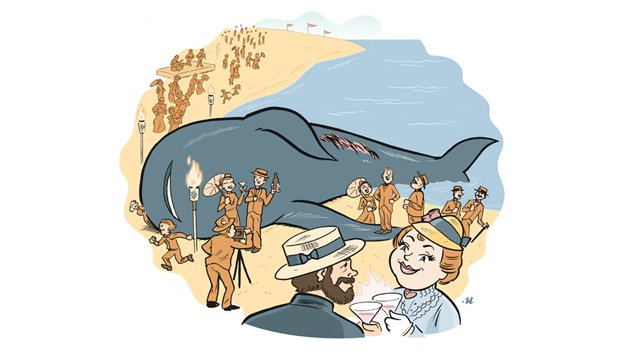

On the strand at Cape Henry.

Whale of a time

On the strand at Cape Henry

Whale of a time

On the strand at Cape Henry

100 YEARS AGO

It’s easier to spot a whale in Virginia waters nowadays than it used to be: Take a whale-watching cruise out of Virginia Beach and, if you’re lucky, “Thar she blows!” A century ago, though, you had to take what you could get, so when a big black whale wound up ashore at Cape Henry on March 5, it was party time. On Sunday, March 7, Norfolk’s City Hall Avenue was “literally black with people” waiting at the Norfolk and Southern railway station to board the “electric trains” to go gawk at the lifeless beast. From early afternoon till 4 p.m., reported the Portsmouth Star, every car was loaded to capacity, thanks to the “propitious” weather and the fact that it was Sunday. The crowd was 5,000 strong, a figure bested only by the mobs that would gather to watch the naval fleet come in.

The New York Times covered the story and explained that the whale had been “hit by some vessel.” The “monster whale” had a “great wound” in its side from the encounter and was found grounded and dying in the surf near the Cape Henry lifesaving station. The surfmen reached the whale in a dory, attached a cable, euthanized the animal, and dragged it to land. The behemoth was 65 feet long and was thought to weigh between three and four tons.

As the day wore on, according to the Star, the whale ripened in the heat and became “very disagreeable.” Still, the animal remained such a draw that plans were made to “preserve him on the beach for several weeks yet, with a view to exhibiting him to visitors.” The impromptu, in situ museum took effort. First, the whale was hoisted above the wrack line, and then workers built a fence around him. After that, a Dr. Norrison of Virginia Beach embalmed the mammal—a whale of an undertaking. The crowds kept coming, no doubt encouraged by the notices that peppered the Star for days. “The Whale is still on exhibition,” read one. “Take Cape Henry Electric Cars. Round Trip Tickets 25 cents.”

Whales still come ashore, of course. “We have between 100 and 150 live and dead marine mammal strandings annually” on ocean and Chesapeake Bay beaches, says Gwen Lockhart, a stranding technician with the Virginia Aquarium Stranding Response Program of the Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center in Virginia Beach. The program collects stranding data on marine mammals and sea turtles.

Most strandings involve bottlenose dolphins, Lockhart says, but each year “between two and four are large whales.” In addition to natural causes, whales strand as a result of human activities, she says—the most common of which are ship strikes or the animal getting tangled in so-called ghost nets, which are fishing nets left floating free in the ocean.

A beached whale will still hold Virginians in its thrall, even though whale-watching cruises are available and popular. “Every large whale stranding I’ve ever seen has attracted a crowd of people and reporters,” says Lockhart. “People hardly ever get to see these magnificent creatures, so even a dead whale is spectacular.”