Johnson chairs are among Virginia’s most coveted homegrown antiques.

I bought a ladder-back chair at a shop in Clarksville. It’s maple, has finials atop the back posts, pegs holding the upper slat to the posts, a shine on the split-oak seat from years of use, and extreme wear to the front rungs. It was tagged, “JOHNSON CHAIR.”

“It’s a cool early-Virginia chair, probably 1820,” says Richmond artist Richard Bland as soon as he sees it. “Non-Johnson.”

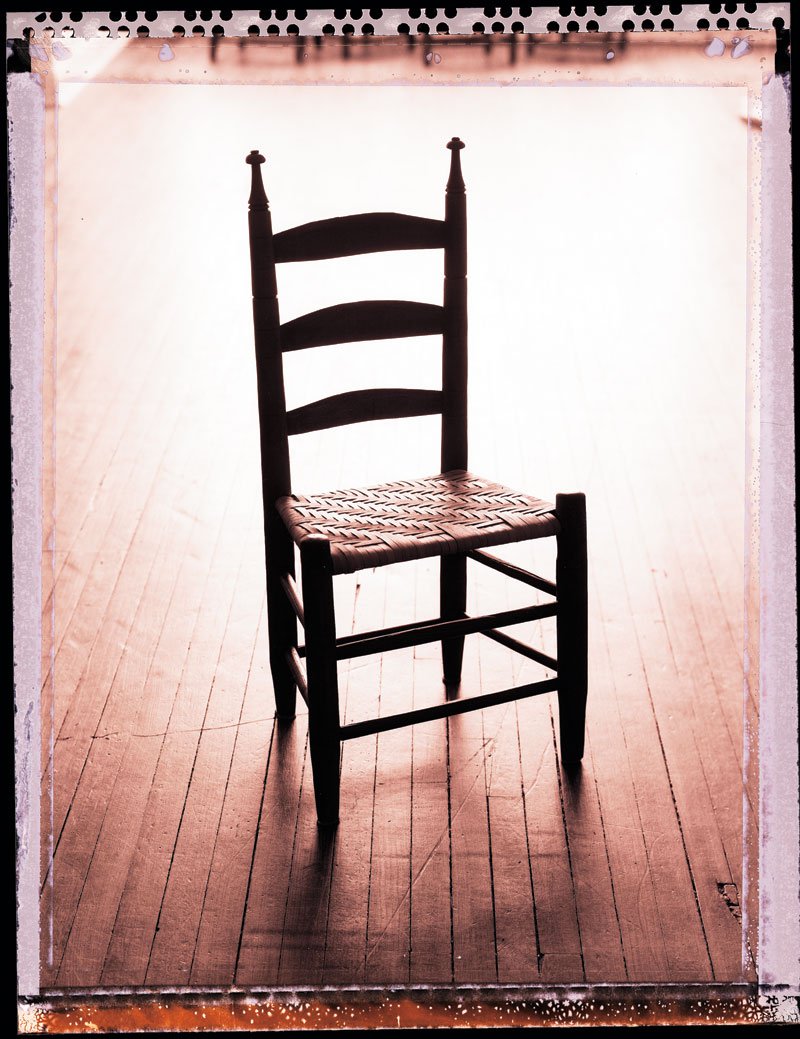

The simple yet distinctive Johnson chairs, made in Mecklenburg County from the 1820s or ’30s into the 1880s, first by Thomas Johnson and later by his son Warner, may be the most sought-after ladder-backs in Virginia, especially in Mecklenburg and adjacent counties. The chairs’ relative ubiquity in Southside Virginia and their strong collectibility have put them in an elite group with Kleenex, Xerox, Nabs and now maybe even Google—products so popular that their names have gone generic.

“You’re reeling in the legend and the sellability,” says Bland. “All over Virginia, any auction you go to, they call them all Johnsons, because the name Johnson has stuck with a chair better than any other.” But Johnson aficionados know the difference and carry a mental list of key traits.

“There are seven things you look for to make sure they’re Johnson chairs,” says Virginia Dare Wright, a retired teacher who lives near Boydton and whose mother was a Johnson, of the chair Johnsons. She enumerates: wedding band, incised ring, square pegs, the finials … .

Dr. Lewis Wright, a retired Richmond neurosurgeon (no relation to Virginia Dare), provides the most comprehensive and technically precise description of Johnson chairs and their construction, in his article that appeared in the November 1980 issue of the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts. It’s the back posts that hold most of the chairs’ Johnson-ness. They were turned on a lathe to produce, at the top end, a rounded cone with a mushroom or ball at its tip, often capped with a button or nipple. Near the cone’s base, two lightly cut rings about a quarter-inch apart form a sort of shoulder, the “wedding band,” just below which the taper is curtailed drastically until the post begins to narrow again several inches above the floor.

Below the first slat is a deeply incised ring, the only other ornament on the post. Visible along the posts are thin work lines, scribed for precise placement of slats and rounds. Side chairs—the dining room chairs that were the Johnsons’ most common style by far—have three slats, the top one secured on either side by a wooden peg through the back of the post.

The chairs were usually maple, rarely walnut. The bottom rounds, especially the front ones, were sometimes made of harder wood, like oak, to resist wear from feet resting on them. Side chairs have two bottom rounds on the front and sides, and one in the back. Seats were made of split oak or rush, as well as red-elm bark. And chairs were left raw, varnished, or painted green or a ruddy brown.

Any trait found in a typical Johnson may be seen in other chairs, too—the work lines, for example. “The work lines locate all the horizontal elements of the chair,” says Mark Wenger. “They all have them. If they don’t, chances are, the chair has been refinished and it’s all been sanded off.” Wenger is head architectural historian on the restoration of Montpelier, the home of James and Dolley Madison near Orange. Studying chairs is his side interest, and his Williamsburg office overflows with antique ones from Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina, in every state of finish, despair, style and stance. He can also attest that Johnsons aren’t the only chairs with pegs holding in the first slat. “A lot of the chairs from Bertie and Northampton counties [of North Carolina] have them,” he says.

Seldom are all the checkpoints met in one chair, but they are in most Johnsons. Johnson chairs also have a posture, or accent, as Wenger calls it. They’re frank; they’re there. The chairs, Wright says, are also “generally stouter than most mid-19th-century chairs.” They’re heavy—“in the size of their components and in actual weight.”

•••••

“They made some fine furniture down through Mecklenburg and into North Carolina,” says Sterling Anderson, a retired Richmond banker originally from South Hill, just east of where the Johnsons farmed and made their chairs. “There is a school of furniture—good, early furniture pieces—and they call it the Roanoke Valley School, because they don’t know who the cabinetmaker was.” These furniture makers created corner cupboards, tables, grand bedsteads and, of course, chairs.

Thomas Johnson was a farmer who took on chair making as a way to make money during the fallow months. At Thomas’ death in 1846, son Warner, 29, took on the farm and the family’s sideline industry. A few years later, records suggest, chair making had become a bigger part of their livelihood, because Johnson didn’t call himself a farmer first. “In the 1850 census of Mecklenburg,” says Anderson, “they called Warner a mechanic. A mechanic would have been someone who worked with his hands and made anything from wagons to chairs to furniture. The interesting thing is where his father learned to make chairs. If there was anyone down there, we don’t know who it was.”

And probably never will. But furniture and furniture makers got around. Ladder-backs, Wright says, were being made in Europe in the 1600s and in America by the end of the century. The Johnson family was ensconced in Mecklenburg by the early 1700s, and ladder-backs were coming of age.

“There are important chair making centers,” says Wenger. “Halifax, Northampton and Bertie counties in North Carolina, and probably this sort of moves west and up the Roanoke Valley.” The Roanoke River crosses into North Carolina from Mecklenburg. Wenger also speaks of Richard Hobday, a chair maker first known in York County, but then, “he’s in Lunenburg, he’s in Mecklenburg and he’s down in South Carolina. These guys are pretty mobile, some of them.”

We can’t pinpoint when the Johnson chair came to be recognized as more than just a good chair, but by 1916 they had enough stature to warrant singling out in the will of Richard Bland’s great-grandfather, Colonel John Thomas Goode, of Boydton. “His will lists every single Johnson chair,” says Bland, “even one that has no seat in it, so it had to have meant something to him.”

By 1937, the chairs’ celebrity had taken a quantum leap. On January 3, the Richmond Times-Dispatch ran in its Sunday magazine section an article by Mary McKinney, of Chase City, titled “Origin of Real ‘Johnson’ Chairs.” The title suggests that other chairs were already being mislabeled, and the blurb called Johnsons popular antiques, so they must have been embraced by a public as widespread as the Times-Dispatch’s readership. The earlier chairs were turning 100 years old and so were bona fide antiques. By the time the Chase City Progress reprinted McKinney’s story 30 years later, Johnson chair collecting was reaching fever pitch.

The popularity of chairs last produced in the 1880s was made possible by two facts: a lot of the chairs had been produced, and a lot had survived. Let’s consider just the chairs made by Warner. Charles Johnson told McKinney that his grandfather could turn out a set of six chairs in a day and made from 150 to 200 sets a year. With a conservative lean, let’s say Warner began making the chairs only upon the death of his father, in 1846. McKinney reports that Warner stopped making them four or five years before he died in 1893. So even if Warner made only 100 sets a year, and only from 1846 to 1888, he produced more than 25,000 Johnson side chairs.

No one knows how many remain, but they fetch a pretty penny when they turn up. Occasionally, someone will still ferret one out for $20 or so, but a side chair normally sells for $250 to $600, sometimes as much as $800. A rare walnut Johnson recently went for $900. And they bring less the farther you get from Mecklenburg, says Chip Pottage, an antiques dealer in Halifax.

March Hutcheson, an auctioneer near Boydton, tells of a woman in Washington, D.C., who asked him to sell a child’s Johnson chair for her. For a child’s chair, it is said, you can name your price—but maybe not if you’re that far away from Mecklenburg. “She heard of what the Johnson armchair brought, and she said, ‘If I took my chair to an auction up here, it would bring $25.’” And this wasn’t just any Johnson child’s chair. It was “that green-painted one” pictured in Wright’s article, a chair of some renown. It wound up going for around $4,000. “I called her on the telephone and told her what it brought,” Hutcheson says. “Dead silence.”

Rarity does command a higher price. The armchair the woman had heard about spawned a bidding war—and brought $7,200, a price so shockingly high, it made the county papers. “Two people on it,” Hutcheson said. And the man who won it “was busting it wide open. Snap, crackle, pop!”

•••••

“They’re good chairs,” says Landon H. “Bumps” Carter, a retired dairy farmer in Boydton who uses Johnson chairs daily. “They’re put together part green and part dry, and you don’t have to worry about them giving out or breaking. You be good to them, they’ll be good to you.”

“They last forever,” says Virginia Dare Wright. “The slats and rungs were seasoned for seven years, and the posts were green.”

Everyone knows about that green wood. “These seasoned backs and rounds were inserted in the perfectly green timber,” wrote McKinney, “so when it dried, they were clinched in the most secure manner.” And any nail in a Johnson chair wasn’t put there by a Johnson. The only thing even close was the wooden pegs in the back of the rear posts.

Pottage calls the Johnson “a good, strong-setting chair. You’re not supposed to rear back in a chair, but you can rear back in a Johnson, and it’s not going to break.” Good thing, because people are going to “rahr” back. Bless the lock joint, the third secret of Johnson stability (although it, too, is found in other chairs, Wenger says).

In many ladder-backs, Lewis Wright says in his article, the four seat rounds are in the same plane, but in Johnsons, the side seat rounds are usually a third higher than the front and back ones. The chair sides were assembled first, and when the mortises were drilled in the posts for the front and back seat rounds, they were drilled through the top third of the side rounds, which were already in place. Thus, the rounds interlocked inside the posts, a highly sturdy arrangement.

Some chairs have escaped virtually unscathed, but others have been abused. They were converted to rockers and back again. The legs ground or rotted down. Toddler’s chairs are often worn from being used as walkers by children just learning to navigate. Slats have been shaved. Legs were shortened so tobacco workers would have a shorter stretch to pick up leaves from the stripping room floor. Finials were whittled down or abraded by leaning back against a wall.

Richard Bland appreciates the character that time has lent Johnson chairs and the variation the makers imparted. He will home in on a finial, covering it in protective plastic wrap, then capturing its silhouette with a profile gauge. This he traces onto a form he devised for collecting data on the chairs. Using an antique caliper, he then measures key diameters along the relief of the finial so he can trace its other side properly separated from the first, giving a true outline. Bland has measured the finials of around 30 Johnsons, as well as other structures and relationships in his ongoing quest to document differences in the chairs.

For Wenger, a chair is a snapshot in time that is most valuable when unretouched. “A lot of people have chairs with the idea of decorating their home with them,” he says. “They want them to fit in with everything, be a nice genteel thing. They get these chairs, they strip them so the finish is gone, they skin them, they bust the seats out of them, and what’s gone is one more document about how these chairs were made.”

The Johnsons also made teen chairs, and table chairs so that small children could eat at the table with the others. There were rockers and writing chairs. Wright mentions that the collection of Prestwould, Sir Peyton Skipwith’s plantation home on the Roanoke in Mecklenburg, includes a large armchair the Johnsons custom-built, possibly for “a portly gentleman of Clarksville.” And Colonial Williamsburg has a heavy Johnson chair that has been fitted with a foot-powered “shoo-fly” attachment for keeping away the pesky insects.

Holding up a photograph he took, Richard Bland points out a Johnson writing chair. “This is Sheriff Sam Farrar’s chair,” he says, speaking of a former sheriff of Mecklenburg County. Helen Massingill, a Clarksville public relations consultant and Farrar’s great-great-granddaughter, says his writing chair resided on her family’s porch when she was growing up in Boydton. The rare Johnson, now sheltered from the vagaries of Virginia elements, has “been in my family probably the whole time.”

Owners’ enthusiasm about Johnson chairs is boundless, and personal. People talk about them like they talk about their dearest relatives. But maybe it isn’t that big a stretch. Around the Massingills’ table are some side chairs, in excellent condition.

“When I graduated from college,” she says, “my Uncle Joe gave me four Johnson chairs to take to my apartment in Washington. Since then, I’ve always had a home with Johnson chairs. When I go visit my children, they have them too. And when I see them, I think, ‘That’s so right, for you to have Johnson chairs.’”

Pointing to one of the side chairs, Massingill describes another source of wear and offers a conservation tip. “The cat got that one,” she says. “It’s better to get cats that don’t scratch Johnson chairs.”

Special thanks to Sterling Anderson for the use of his Johnson chair collection in the photographs.