Sam Jones and Marguerite Upton were each raised in Norfolk’s Berkley neighborhood and came of age in the Roaring Twenties. Each went on to a life of great wealth and notoriety—but they could not have been more different.

The Iron Forger and the Gold Digger

The Iron Forger and the Gold Digger

Peggy (left) at the Hollywood Restaurant in New York City with Mr. and Mrs. Clark Cable, 1934

The Iron Forger and the Gold Digger

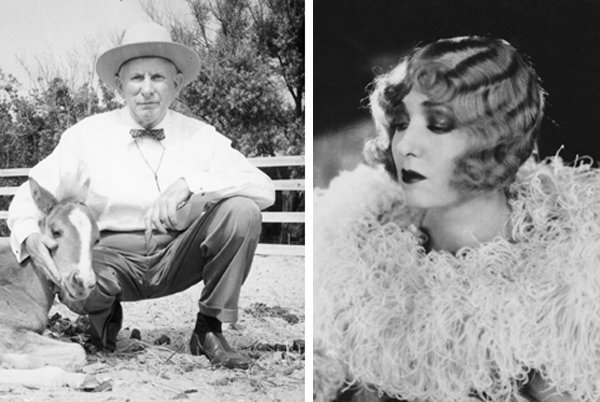

Jones and family at Berkley Castle on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina

The Iron Forger and the Gold Digger

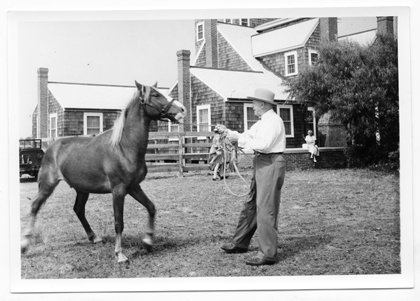

Jones and his beloved horse, Ikey D

The Iron Forger and the Gold Digger

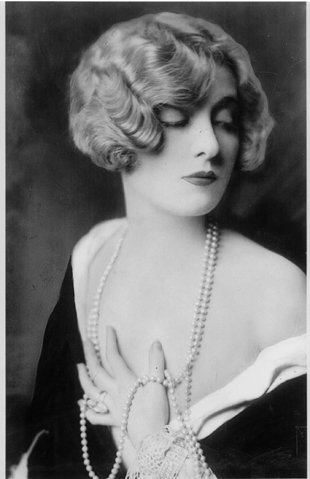

Peggy Hopkins Joyce, 1920s

The Iron Forger and the Gold Digger

Peggy Hopkins Joyce in Palm Springs, 1933

He wrestled industrial-strength steel into heavy machinery parts and cast an invention that revolutionized the railroad industry. She twisted the most delicate of precious metals—and the men bearing them—around her pretty fingers. And they both made a bundle doing it. • Samuel “Sam” Jones and Marguerite “Peggy” Upton were born in the same year and grew up in the same place, and each was entirely self-made. Other than that, they had nothing in common. Jones was a straight-laced and quirky foundry man. Upton, leveraging her beauty and hedonistic spirit, was a true courtesan—one of the most talked about women of the 1920s and ’30s—and the quintessential American gold digger. She was the inspiration for the iconic Lorelei Lee, heroine of Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes—and the first person, it’s been said, to be “famous for being famous.”

Born in 1893, Upton and Jones spent their formative years in Norfolk’s Berkley neighborhood—just a few blocks from each other. They came of age in the Roaring Twenties, an era billed by many historians as the birth of modern America. It was a time of unprecedented change, and it offered untold opportunity for those with moxie and ambition, which Upton and Jones had in spades.

Their styles, however, were completely different. Jones’ beliefs and behaviors, rooted in the Victorian era, remained rigidly moralistic throughout his life. Upton’s predilections would make scandalous tabloid headlines even today. She didn’t care if her opportunistic marriages (she had six) and torrid affairs (too numerous to count) wagged tongues and dropped jaws. “Better to be mercenary,” she said, “than miserable.” Together, they represented the yin and yang of the most free-wheeling, unorthodox age in American history.

Although the Berkley section of Norfolk is small and unassuming today, it was a bustling, wealthy township in the late 19th century. One of the oldest communities in Virginia (established in 1664), it was “the most prosperous in the Tidewater region” by the time it was officially incorporated in 1890, according to local historian and author Ray Harper. This was in large measure due to its strategic location—adjacent to rich forests (lumber was a boom industry following the Civil War) and at a prime shipping vector on the Elizabeth River. Not surprisingly, shipyards and other maritime industries were also big business.

Downtown Norfolk, with all its glamour and grit, was a short ferry ride away. Here, a number of theaters and entertainment venues offered both vaudeville and its slightly seamier cousin, burlesque, and featured the likes of Harry Houdini, Al Jolson, Mae West and Lillian Russell. In 1907 a lavish world’s fair, the Jamestown Exposition, brought acts and visitors from all over the world and launched the global voyage of Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet. None of this excitement was lost on Berkley’s younger generation.

Sam Jones was born in Swanquarter, North Carolina—a town about 150 miles south of Norfolk. His father was the town postman, his mother a housewife. Together, they imbued in their four children respect for hard work, discipline and clean living.

But opportunity lay elsewhere, and at age 13 Jones moved to Norfolk, the closest “big city” to Swanquarter. He got a job at Berkeley Machine Works and Foundry and, amazingly, became its president by age 19. At 26, he owned the company. His meteoric success was due as much to his vision as his verve, taking the shop beyond its customary “down the river” (piecemeal) work to large and sustaining contracts with the U.S. Navy, Bethlehem Steel and the Norfolk Naval Shipyard.

Jones was an exemplar of the Puritan work ethic, and also an innovator and inventor. He conceived the Berkley Stoker, an automatic coal-loading apparatus that significantly improved the method and efficiency by which railroad engines were fueled. He made a fortune from it, and from his booming company.

Jones was intensely inquisitive and, newly rich, acquisitive as well. If he found something interesting or attractive, he bought it, often in multiples. These purchases ran the gamut. The first time he saw a Barcalounger (reclining chair), he was fascinated and bought 20 or so to be shipped to friends and employees. He also liked fine art and antiques. Ken Farmer, owner of Ken Farmer Auctions, has handled several Sam Jones’ estate auctions and, in a 2009 story in Portfolio Weekly, characterizes him as “a voracious and eclectic collector,” adding: “He bought some crazy stuff, but it was all really cool.”

Jones also liked land. In 1926, he bought Sajo Farms, a working plantation that eventually totaled 800 acres, encompassing most of what later became northern Virginia Beach. In 1939, he built a 22,000-square-foot manor house at Sajo Farm, where he raised his family. Much of the original property was subdivided and sold to developers following Jones’ death in the late seventies. (In August it was on the market for $10 millon.)

In 1939, Jones visited Ocracoke, North Carolina for the first time. He was introduced to it by his first wife, the former Mary Ruth Kelly, whose family goes back generations on the island. Jones loved Ocracoke with a passion—so much so that he built four houses on the island, starting with the Berkley Castle, his massive hunting and fishing lodge. He essentially served as the island’s off-season cottage industry, hiring workers not only to build his houses there, but also to maintain and service them.

He was more than generous to the Ocracoke community, buying the island its first fire truck and ambulance, funding local churches and Boy Scout troops and filling other unmet needs. He even kept an apothecary in his hunting and fishing lodge to tend to islanders’ injuries and illnesses. Longtime Virginian-Pilot columnist and friend Lawrence Maddry once described Jones as the “squire of Ocracoke,” and wrote: “No one knows all the stories…for Sam was too big to chronicle. [He] was one of the wildest things ever tossed by nature on to that weather-beaten island….”

Jones was wild, but always in the most wholesome of ways. He entertained extravagantly and often, hosting square dancing parties, costume balls and sing-alongs. No smoking, however, was allowed anywhere in his dominion. Drinking was permitted—grudgingly—in the “Coca-Cola room” of The Castle.

According to historian Harper, Jones was “a stiff, proper man who wore a necktie at all times.” Even at the machine shop he would only entertain a spiel from a salesman if the vendor was properly attired. Maddry recalled: “He dressed very much like a ship’s captain of a previous century… imported, pleated shirts, the collar crossed underneath with a black band of cloth like a choir boy…a ruby pin winked from one of the buttonholes… (and) he was seldom outdoors without a broad planter’s hat on his head.”

Jones kept a rigorous schedule, often working seven days a week, rising at 4 a.m. and getting to bed by 8 p.m. Even at the Whittler’s Club, a cozy waterfront hangout he built for his retired fishing buddies, he insisted on decorum, distributing “membership cards” printed with rules of conduct. Among them: “The only way a member can lose his membership is by telling smutty jokes.”

Every now and then Jones’ obsessive priggishness could be a source of embarrassment. Jones was friends with, and a great patron of, Alphaeus Philemon Cole (1876-1988), a famous American portrait artist. An enthusiastic promoter of all he believed in, Jones at one point inveigled Maddry to persuade CBS TV to arrange a national interview with Cole. The interview took place and was going smoothly until the interviewer, intrigued by Cole’s “Blank Canvas” self-portrait, asked the artist if he’d ever engaged in affairs with his models. Incensed, Sam emerged from backstage brandishing a broom and began swatting the interviewer and the production crew. The interview was unceremoniously aborted.

Standing on principle also cost Jones his freedom for the better part of a year. In May 1959, he stood trial for tax evasion. The charges stemmed from write-offs he took for client entertainment at his homes, all of which Jones felt were entirely justified. He pled guilty, was sentenced on all six charges, and levied a $30,000 fine. Then 67, he remanded himself into custody and served more than six months in the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. On his release, Sam told foundry vice president and pal Red Halsey, “They didn’t know anything about running a prison up there. They should have let me take a crack at it.”

Jones’ last years were spent as he’d spent his entire life—doing exactly what he pleased, which included working hard (he was returning from a full day’s work at the foundry the day he died in 1977). Despite his large family—Sam had five children with his first wife, two with his second, 16 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren—he is buried alone in a sand dune on Springer’s Point, Ocracoke, next to his beloved horse named Ikey D. According to grandson K.C. Jones, Ikey D had been buried standing upright so Jones could “jump on and ride to glory” when his own time came.

erkley launched another star in Peggy Upton. Her father ran the Norfolk Shaving Parlor, which was the most popular spot in town at the turn of the century. Peggy visited the shop often, bringing dinner to her father and charming the customers. According to her cousin Elizabeth Nixon, quoted in Constance Rosenblum’s 2000 biography, Gold Digger: The Outrageous Life and Times of Peggy Hopkins Joyce: “People thought she was real cute. The men getting haircuts talked to her and … were carried away with her.” Later in life, as her wealth and fame grew, Hopkins was often described by journalists as “the Norfolk barber’s daughter,” adding considerably to her tabloid mystique and scrappy appeal.

Sam and Dora Upton, Peggy’s parents, did not have a happy marriage. Ultimately, Dora left the family and moved to Richmond for a time, whereupon she divorced Mr. Upton and quickly remarried. Sam Upton became Peggy’s custodial parent—a highly uncommon arrangement in the early 20th century—and relocated to Farmville with his 10-year-old daughter. There, he too remarried and started a new family.

The move to a rural town didn’t suit the free-spirited and attractive Peggy. She pined for Norfolk, and while an adolescent she convinced her father to let her move back to the city to live with her grandmother. It was the first demonstration of her ample powers of persuasion.

In 1910, at age 17, Peggy met and married the first of her six husbands. According to her 1930 autobiography, Men, Marriage and Me, which is amusing but largely apocryphal, she met Everett Archibald on a trip she took out west with a vaudeville cyclists’ troupe. More credible reports indicate that she met him at a resort in the fashionable Ocean View area of Norfolk then known as the “Coney Island of the South.” Regardless, a whirlwind courtship and brief marriage followed with a man Peggy believed to be a bonafide millionaire: “His father is the Borax King of America!” she breathlessly penned in her journal. While from a prominent Denver family, Archibald was, in fact, a traveling salesman for a Utah wholesale grocery company. Still, he was wealthier than anyone Peggy had ever known.

In her memoir, Upton claims the marriage fell apart after 72 hours, due to her utter incredulity (and horror) at the carnal realities of marriage. “[My] life is ruined,” she wrote, adding: “I hate men…hate them, hate them. They are nothing but animals.”

Coy protestations notwithstanding, there is evidence that she was sexually experienced by the time she met Archibald. The marriage, strained under rumors of her indiscretions, collapsed in full after Archibald walked in on his wife in flagrante delicto.

Hopkins’ only child came from this brief union. A son named Everett was born in Richmond, where her mother was living, in April 1911. Four months later, the child died when a relative accidentally overdosed him with opium-laced syrup. He is buried in an unmarked grave in Berkley’s Magnolia Cemetery (where Peggy’s mother is also interred). After the boy’s death, Hopkins and her family rarely acknowledged his existence.

After her first marriage ended, Peggy moved from Norfolk to Washington, D.C. Here, her beauty came to the attention of dress salon proprietess Madame Frances, who hired Peggy to promote her frocks at vaudeville shows and the District’s choicest clubs. She no doubt met Sherburne Hopkins, who would become her second husband, at one of these upscale watering holes.

Hopkins was the black sheep of a prominent family—a hard-partying playboy and ne’er-do-well. It’s unlikely that the 20-year-old beauty loved Hopkins, but he had an impeccable pedigree—he was a Mayflower descendant and son of one of the capitol’s best-known international law attorneys. As Peggy recorded in her journal, “Sherby is a millionaire and very prominent socially, and a girl cannot marry a millionaire who is prominent socially every day.”

Though her chances to marry a millionaire didn’t come every day, Peggy rarely missed an opportunity to squeeze a wealthy paramour bearing gifts into her hectic life. And she wasn’t at all abashed about it; to Peggy it was all a well-earned quid pro quo. “I may be expensive,” she famously said, “but I deliver the goods.”

Peggy and Sherburne lived on the top floor of his mother’s elegant town-home in D.C.’s fashionable DuPont Circle neighborhood. Here she became acquainted with politics, luxury and the perils of disapproving in-laws. Living with her mother-in-law was untenable, and as would become a pattern with Peggy, the marriage dissolved into boredom and bickering and was effectively over within its first year.

By 1915, bored with Washington D.C. and fed up with the Hopkins clan, she struck out for New York with the vague notion (based on the fleeting vaudeville stint of her youth) of earning her living as an actress. Peggy had no real theatrical talent, but she was spunky and alluring. In customary dramatic fashion, she feigned concern over the propriety of the move in her journal: “I suppose mother would not like Broadway, she would think it wicked and vulgar, but it is not any more wicked and vulgar than Norfolk; it is only more tired and wise.”

Her first big break was to star in a “Style Show”— a glorified fashion show—at New York City’s Palace Theater. In 1916 she had bit parts in a few silent films, and a year later she became a Ziegfeld Girl, functioning, as many showgirls did, as “eye candy” rather than as a performer. During this period she met and befriended a number of genuine stars, including Will Rogers, W.C. Fields (with whom years later she shared billing in the comedy International House) and Fanny Brice, whose advice about “how to handle men” she quoted freely in her memoirs.

The Ziegfeld gig catapaulted Peggy into the career for which she was best suited— that of well-kept concubine. She attracted and engaged so many wealthy suitors that “in certain circles,” writes Rosenblum in Gold Digger, “Peggy was coming to be regarded as nothing more than a high-class call girl.”

Peggy’s next move was to live theater. She landed a few parts with the reigning king of Broadway, Lee Shubert, but her performances—and the consequent reviews—were scathing. Writer Heywood Broun used the term “shockingly bad” to describe her starring role in A Place in the Sun. Another critic called the same production, “about the worst play it would be possible to witness… and live.” She pretended to be upset by the bad notices, and quickly found backstage consolation in the arms of millionaire playboy Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, among others.

By then Peggy had captured the attention of America’s burgeoning tabloid press. Her every move, no matter how banal, was trumpeted, whether bobbing her hair or acquiring a pet goat. The New York Evening Mail even ran a contest for its readers to design an Easter bonnet for Peggy. The public couldn’t get enough of her.

When her theater career took her to Chicago in the spring of 1919, Peggy met her third husband, the first and only true millionaire that she would wed. James Stanley Joyce was a lumber baron from Clinton, Iowa who had taken in, and been left slack-jawed, by many of Peggy’s performances. Initially, after noticing him noticing her, she dismissed Joyce to a colleague with the comment, “Who’s the boob?”

His fortune did not impress her at first. “Lumber does not sound very romantic,” she said. What she did have use for, though, was expensive jewelry, and Joyce got the message. The morning after their first date, he presented her with a large emerald. “Really it was very nice of him,” she wrote in her journal, “Of course I would rather have had a diamond but anyway I suppose emeralds are worth a little money.” She was a bit more gratified when she got the bauble’s $20,000 appraisal.

Then Joyce upped the ante. He put a railroad car at her disposal, bought her a platinum watch and promised to help her get a divorce from Hopkins, if only she would marry him. Peggy relented, and two days after she was granted her divorce in January 1920, she wed again—ironically, in a simple civil ceremony. The couple set up house in Miami’s Coconut Grove, in a furnished manse purchased by Joyce for $200,000 and adjoining the Williams Jennings Bryan estate.

Joyce was in over his head. He was not handsome, and did not have much of a personality—Peggy called him “a stiff.” As Rosenblum writes, “[Peggy] realized from the beginning that the marriage would be a sham. But twice before she had chosen husbands on the basis of money and never regretted her decisions.”

That was true. When Joyce broached the idea of buying a yacht, Peggy demurred, saying: “I’m always seasick on yachts.…” and instead convinced him that a $300,000 pearl necklace would be a more prudent investment. Then came the home improvements—among them, an $80,000 marble swimming pool and a house for her pet monkeys. By several accounts (including her own), Peggy burned through $1 million in a week-long spending spree. Though she loved her marital salary, she wasn’t wild about the job, so for sexual thrills she turned to other men.

After a year of playing cuckold and banker, Joyce filed for divorce. Peggy, vacationing alone in Paris, learned of the move from a reporter. The sensational divorce trial—rife with tales of violence, drunkenness and sexual scandal (including Peggy’s assignations with princes and dukes)—sparked more than 4,000 newspaper articles in the spring of 1921 alone. A Hearst newspaper editorial took a dim view of the Berkley barber’s daughter, writing: “Out of what childhood environment sprang this modern Cleopatra … who married three millionaires in as many years and lured princes, a notorious crook and even a hard-boiled bartender to worship at the shrine of her fascinations?” It was also during this period that two of her suitors—one a high-ranking Chilean diplomat—committed suicide for want of her. The scandals resulted in an unprecedented ban of Peggy’s pictures, past or future, by the Motion Picture Theater Owners of America.

Undaunted, Peggy headed to Hollywood to reinvigorate her acting career. There she met the world-famous Charlie Chaplin, whose lusty love life was almost as legendary as his stardom. According to Photoplay magazine, “In Peggy, Charlie found the greatest sex-lure he had ever encountered.” The affair didn’t last, perhaps because she was too wild and randy for even Chaplin, or perhaps he proved too much of a tightwad. In fact, this time around it was Peggy who offered up the valuable currency— the stories she told Chaplin about her life became the basis for A Woman of Paris, the only melodrama he ever produced and the movie film critics consider his greatest artistic achievement.

Hopkins continued to scorch her way through Tinseltown. By her own count she got at least 50 marriage proposals—and in 1924 accepted one from Swedish nobleman Count Karl Gustav Morner, making Peggy bonafide royalty, not just a tabloid princess. But the title was apparently the Count’s only asset. As Peggy soon discovered and later recorded, “He has a castle in Sweden or rather his family has, but I do not think they have much besides the castle…However, a castle is something.”

Something, but not enough. Once Peggy realized, just two months into the marriage, that she had to pick up the Count’s tab at the dry cleaner’s, it was over.

After that interlude, Peggy resumed her Hollywood career and starred in The Skyrocket in 1926, a picture financed by Boston banker Joseph Kennedy and extravagantly promoted. It played to mixed reviews and did poorly at the box office, but was nevertheless a boost to Peggy’s fame. She left Hollywood shortly after its release and headed back to Broadway. There, she flopped spectacularly in a play her married paramour, Ray Goetz, wrote and produced specifically for her, called The Lady of the Orchids.

Throughout the 1920s she was a staple at New York City nightclubs like El Morocco, The Stork Club, and especially Texas Guinan’s Café des Beaux Arts. Peggy “personified life after the sun went down,” a former press agent said of her. She cropped up in The New Yorker cartoons, the lyrics of several Cole Porter songs and in countless magazine and newspaper articles.

During this period she collected some of her most impressive lovers — and baubles. The very-married father of four, auto titan Walter Chrysler, gave her the 127-carat Portuguese diamond, now the crown jewel of the National Gem Collection located in the Smithsonian. Her celebrity crested in the 1920s, but by decades’ end began to ebb.

By the start of the Depression, the public was beginning to tire of Peggy and her social exploits. She turned to writing, first doling out advice to the lovelorn in a newspaper advice column, ironically touting the virtues of true love over money. She was hired by another publication as a “celebrity stringer” to cover—fittingly—a scandalous and steamy love triangle/capital murder trial.

Peggy had always relied on her men for her income. When funds ran low, she would sell a piece of jewelry for cash. Generous in the extreme with other people’s money, she was notoriously tight-fisted with her own, according to biographer Rosenblum.

In 1930, she published her autobiography Men, Marriage and Me. Author and esteemed editor Malcolm Cowley reflected in his memoir, Exile’s Return: A Literary Odyssey of the 1920s that the book launch “tea,” as promotional parties were sometimes called during prohibition, thrown by publisher MacCauley & Co., was the most elaborate he’d attended, a fact that steamed the genuine literati of the day. In 1933 MacCauley took another gamble on Peggy’s mass market appeal and published her novel Transatlantic Wife. Biographer Rosenblum characterized it as “so excruciatingly awful as to be extremely, though inadvertently, funny.”

In the early 1930s Peggy made one last run at vaudeville and also starred in her final movie. It was International House, a bawdy comedy co-starring her old acquaintance W.C. Fields, in which she essentially plays herself and parodies her own reputation.

By then Peggy’s looks had deteriorated, and her once- recreational drinking had become a more serious pursuit. Her behavior became coarse and aggressive; she was implicated in ugly nightclub fracases during which she might let fly with her signature blue language, or even throw a punch or two. There was no longer any pretense at courtship or romance on the part of the men who frequented her living quarters. She was ultimately reduced to a public joke—her name shorthand for an empty-headed, promiscuous gold digger.

Being on the skids did bring her home more often. Although her conservative southern relatives may not have flagged their kinship with Peggy, they still considered her exotic and glamorous and flocked around whenever she came to town. In Berkley, she would always be welcome; always be a star.

Peggy would marry two more times. In 1945, she married Anthony Easton, a divorced, 38-year-old engineer who believed Peggy was 39 (she was 52). The marriage was over within six months. A few years later she married Andy Meyer, a bank clerk 22 years her junior. This was, by anyone’s standards, her most successful union, lasting until her death from lung cancer in 1957. Meyer was unprepossessing, but he genuinely loved Peggy and saw beyond her sagging exterior to the glory of her earlier years. She basked in his adoration.

In 1950 Life magazine included Peggy Hopkins Joyce on a list of women said to “have left a lasting imprint on the modern era.” The publication diluted the dignity of the distinction, however, describing her as “an ostentatious Ziegfeld Girl who became famous mainly for marrying millionaires.” Still, as Rosenblum noted in Gold Digger, Peggy Hopkins Joyce “should be remembered… for what she represented… the harbinger of a new age” in which a celebrity could be self-created—and perpetuated—“with the right kind of chutzpah and media savvy.”

Though she’d been the Jazz Age siren who was once one of the most talked about women in the world, she merited but a small obituary in The New York Times and a few lines in Variety when she died in 1957. She is interred in Mt. Pleasant, New York.

Peggy led a shallow, materialistic and opportunistic life, but no one could accuse her of being self-deluded. “Deep inside me ever since I was a little girl,” she wrote, “I have always wanted nice things and luxuries and love and I suppose once or twice I have said to myself ‘Why be beautiful if you cant (sic) have what you want?’”