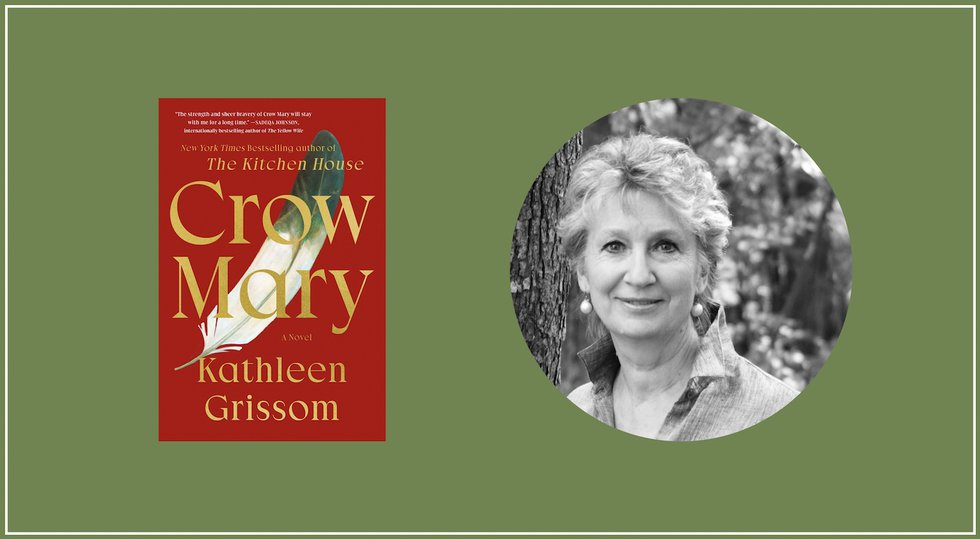

Exploring an indigenous 19th-century woman caught between two cultures

Konstantin Rega: Where did this interest in Crow Mary come from?

Kathleen Grissom: Well, I was visiting Fort Walsh in Canada with my parents. That’s near Cypress Hills, where the first Northwest Mounted Police established a fort. There were docents who were dressed to tell of this massacre that had happened back in 1873. And I was drawn to this sort of a hill where a young woman was standing and she was talking about her experience while she was there at this massacre.

And as she was speaking, it just became almost surreal for me, where I kind of lost the words, and I was just looking at her and I thought “I’m meant to write about her.” And that was it. I call it a spiritual gift, sort of like a spiritual inspiration. That’s the way my other two were as well, where I just knew what I was supposed to do.

And have you always been interested in writing?

I started late to the game; I was about 50. It started when I wrote The Kitchen House. We had moved to Virginia from up north, so about 30 years ago, and we were renovating this old place. This beautiful place had been a stagecoach stop in a tavern.

One day, we were shown an old map and, about a half mile away from the tavern, was a handwritten notation: Negro Hill. And I just became almost obsessed with finding out what happened there. After meeting with an old African American woman, something of a local historian, she suggested that I write my own story because I couldn’t find a cohesive story about what happened there.

And so I thought, well, I don’t know anything about this writing business. I’d written a lot of bad poetry up until then. But she said to me, “Why don’t you pray on it?” And I thought at the time, well, I can pray all I want, but I knew I didn’t have it in me.

But one day I was coming back from the stream on our 25 acres, looking at where that hill was, and said out loud, “What happened there?” Back in the house, I picked up my pencil to start journaling.

I usually write any freeform thoughts that come to my mind. It was as though a movie started to play out. And in that movie, I started to write what I was seeing. And I was just pulled into it. That’s when I saw the prologue of The Kitchen House.

As with many historical fiction books, how did you balance both fact and fiction?

It was a challenge for me because the previous two books were both fiction. And the characters really told the story. In this I had to work within some parameters, some documentation of her life. And she was a tough cookie from all the little bits and pieces that I was able to gather.

But then I went to see Dr. Janine Pease who founded the Little Big Horn College on the Crow Reservation in Montana. And I had been told about her by a lot of the elders. So I was a bit intimidated when I went to her office because I thought: Oh, boy, she’s also going to be one tough cookie. So I went into her office, and she was sitting in this little cramped space, and she had a grandchild on her lap. Then she started to talk to me about the Crow people. And I was so astounded by her gentleness. And I thought: I’ve been wrong about Crow Mary all along. I thought she had to be this really tough, mean person, but she can have strength.

So that was where I began to get some of the reality of what she was really like. And I tried to work, not within the confines of my own mind, but to allow her to just come through and be herself.

What writers or books have inspired you along the way?

Oh, gosh. I read like I’m eating popcorn. I’ve always been in awe of writers. You know, ordinary people who write extraordinary things.

I do say Robert Morgan—who is a Southern writer—he wrote this book called Gap Creek. And I was so enamored of that book. He put me right there. And then he came to the Charlottesville Festival of the Book. I was in a quandary about writing The Kitchen House. I thought: I don’t know how to do this. So I sat in the audience, and as soon as he started to read, I thought, that’s what’s supposed to happen. That little girl is supposed to tell the story. And that got me started. But I get something from every writer.

What do you want readers to get out of it?

People ask me that all the time. And from the beginning, my goal was to immerse myself enough in the culture, that her voice would be comfortable coming through me. And when I do my research, it’s almost as though I’m setting the stage. Then the characters can come, and I give them free rein to do or say whatever it is they need to tell their story.

I don’t see it as my business to dictate what someone should get from that story. I think different people will glean different things. But when we take the time to understand another’s culture, well, we can relate to it because we usually have something very similar. We simply see it in different ways or speak about it in different ways.

Get a copy at The Bookstore.