Adventures in nomenclature.

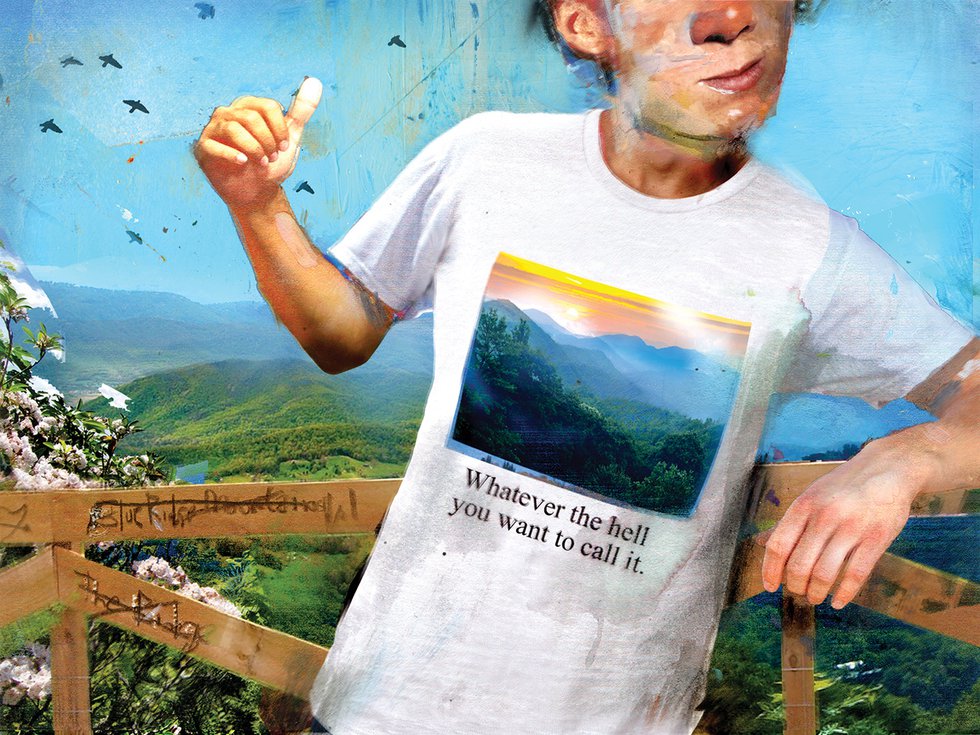

Illustration by David Hollenbach

From my living room window I can see a ridge. My U.S. Topo map says the top of it is only 800 feet higher than my living room. That means that by the official standards once used by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (but dropped in the 1970s, like the U.S. Geological Survey had done a half century earlier, because, according to the USGS website, “broad agreement on such questions is essentially impossible”), the ridge would really only be tall enough to be a hill. To officially be a mountain, when such things were official, it would have to be even higher—1,000 feet.

Yet, many of my neighbors and folks in nearby Hillsboro call this hill-sized ridge out my window the “Blue Ridge Mountain.” When I asked one of them how he could possibly call this very long ridge a “mountain,” the Northern Virginia native said simply, “That’s what we’ve always called it.” He told me to look it up in Wikipedia. Sure enough, there it was. “The Blue Ridge Mountain” of Northern Virginia.

With Wikipedia, though, you want to check the sources. In this case, there was only one: A website called Peakbagger. Sure enough, when I clicked on the link for Peakbagger, up came a page with the headline, “Northern Virginia Blue Ridge.”

Now, this neighbor is perhaps not the best source for clarifying the question of what to call the ridge I see every day. You see, he grew up close to a ridge known as “Short Hill,” which is also referred to in those parts as “Short Hill Mountain.” Paradoxical, to be sure.

The dictionary offers no help either. In some, “ridge” is interchangeable with “mountain range.” Great, except that when you look up “mountain range,” it’s defined as, to quote one, “a line of mountains connected by high ground,” which our single, something-like-50-mile-long, 800-foot-high bump is not.

Now, for most Virginians, there is no conundrum here. From my survey of more than two dozen living south of Shenandoah National Park, where the landscape towers and sprawls, it’s all just part of the range called the Blue Ridge Mountains.

But for folks north of SNP toward Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, all continuity of terminology dissolves. There, it is just one long ridge with the Appalachian Trail on top of it until it dives off Loudoun Heights into the Potomac.

Confused? Since we moved three years ago to this house six miles south of the Potomac River, I’ve been searching for some sort of definitive answer on this issue of what to call this thing. I have found only a mountain-sized Tower of Babel. But I keep asking. And I keep getting teased for asking.

“That’s a dumb question,” says 92-year-old Bill McDonnell of Winchester, who has hunted and hiked the forests and mountains of Virginia and West Virginia, as he says, “in every direction from Winchester for 100 miles for the last half century.” His wife and son posit he may know the region better than any other person alive. (I hiked six miles with him in December and he knew the name of every mountain, hill, knob and ridge within eyeshot. This, as I panted to keep up with a 92-year-old man who survived combat in both WWII and the Korean War.)

“They’re the Blue Ridge Mountains,” McDonnell says. “All of it. You should know that. That’s what it’s been called forever.”

Now wait, I say. What if you drive from Winchester toward Washington, D.C. You take Highway 7 to Leesburg and “you cross the Shenandoah and go over what?”

“The Blue Ridge Mountains,” he says. Then he pauses. “It’s maybe the Blue Ridge Mountain there.” He pauses again. “Maybe the Blue Ridge. You go over the ridgeline there.”

“Which is it?” I ask.

Another long pause. “I guess it’s all of them at that point,” says McDonnell, who actually worked on the ridge for 20 years at the Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center.

“I’ve actually called it all of them.”

At what point to the south do old-timers start referring to the ridge as more of a range, I ask him. When does the term “The Blue Ridge” start fully giving way to the term “The Blue Ridge Mountains”?

“I guess as you go south into the Shenandoah National Park and the ridgelines get higher and the hills get higher, you hear people really start saying ‘Blue Ridge Mountains,’” he says. “Then the nomenclature stops being in question.”

So, I’m going with McDonnell on this one. This thing I’m staring at out my window is the Blue Ridge.

As for where it ends and what you want to call it wherever you are, I also agree with McDonnell: “It’s whatever the hell you want to call it.”

This article originally appeared in our April 2018 issue.