Ancient and armored, the longnose gar is a long-lived survivor.

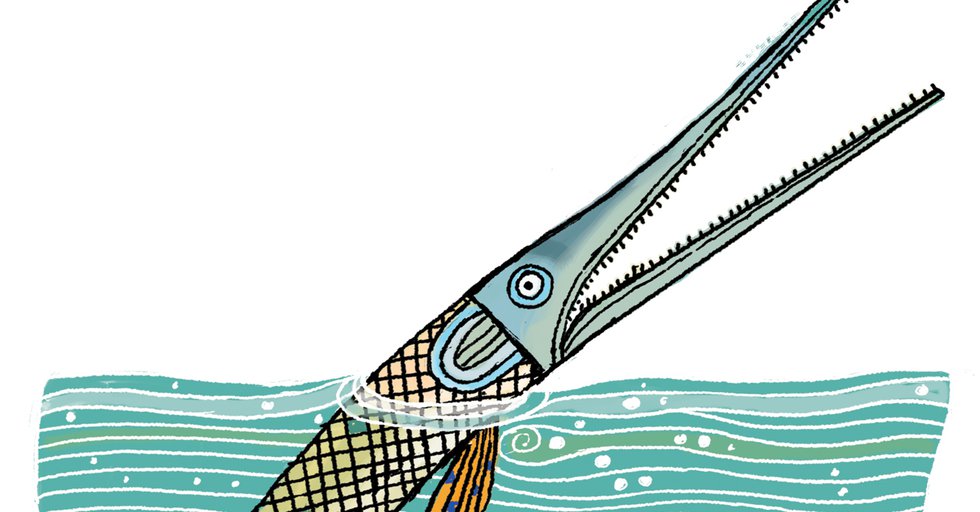

Illustration by Robert Meganck

Marine scientist Patrick McGrath’s interest in the longnose gar began as a case of what you might call academic bycatch. Now a staff member at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), he was then a master’s candidate studying white perch and striped bass, when, on the water one day retrieving a gill net, “We pulled up this almost-three-foot-long ugly fish and I was like, ‘WHAT is THAT?’” he says.

Curiosity to find out more about the long, needle-pointed fish in his net would lead McGrath eventually to a doctoral dissertation studying these ancient survivors, a species that has lived, largely unchanged, for more than 100 million years.

Longnose gar are native to the Eastern half of North America, typically inhabiting slower-moving waterways. While according to McGrath they have traditionally been thought of as a freshwater species, in fact, “they can withstand some pretty high salinities,” he says; they have been spotted in the ocean off North Carolina and caught by people fishing in the Gulf of Mexico. In Virginia, the gar’s range includes both fresh and brackish waters.

The fish, which can grow to three feet or more in length and live more than 20 years, look like swimming darts and get their name from their most obvious feature: a long, pointed snout that isn’t really so much a nose as a mouth. That long jaw is equipped with an impressive display of sharply pointed teeth, which not only help the gar enjoy its status as an apex predator, but also explain one of its more whimsical common names, “scissorlips.” With these teeth, gar snatch and ensnare their prey—almost always other fish—with a sudden sideways swipe, and then swallow the meal whole.

They aren’t picky eaters, either. Whatever is the most abundant fish on hand, up to about 300 millimeters long, will do, says McGrath. “If it’s in front of their face, they are going to eat it.”

Despite the menacing appearance of all those teeth, gar are not aggressive and pose no danger to humans; there has never been a documented case of one attacking a person.

Nor do longnose gar deserve their reputation among some commercial and recreational fishers as a threat to other fish populations, says McGrath. In the cold winter months, when their activity level is greatly reduced, the fish eat very little. “Of all the gar we have caught in those months, there is never any food in their stomachs,” he says, and even when they are feeding most heavily during warmer months, “their digestion is pretty slow—somewhere between 18 and 24 hours for them to actually digest a fish—so they are not consuming everything in the rivers 24 hours a day.”

Besides its pointed front end, the other most notable feature of a gar is the hard scales, a virtual plate of armor, that cover its body. “Scales and jaw are really all gar is,” says McGrath. The longnose gar’s scientific name, Lepisosteus osseus, roughly translates to “bony bony-scale,” which should give you an idea of what it’s like to try to get into a gar. Ever seen someone trying to work through sheet metal with a pair of heavy-duty tin snips? It’s something like that.

The scales make the adult fish impervious to virtually all predators (though apparently alligators will occasionally eat them as a crunchy snack). Nevertheless, people do sometimes make the effort, though McGrath seems dubious that the reward is worth the labor. “Mushy,” is his verdict, and while the meat can be fried up with potatoes and onions, he says, “I have heard people say add plenty of potato and onion and very little gar.”

Remains of the fish have been found in the trash pits at Jamestown, however, and apparently were eaten during the starving time, which raises an interesting question: Did the desperate Jamestown settlers sample the roe as well?

This would have been a bad idea. Although female gar can bear a substantial number of large eggs, the roe is poisonous to humans and will make you very, very sick.

Interestingly, the gar also has the ability to breathe air. “They have a connection between their mouth and their swim bladder that allows them to gulp air,” says McGrath. The swim bladder in turn is very vascularized, allowing the fish to use the oxygen. The behavior seems to be related to water temperature, according to McGrath, and “come summertime, you’ll also see them coming up and taking a breath.”

In some areas of Virginia rivers, longnose gar are a common sight, idling in a sluggish current, serene in their armored plating—a fish that swam with dinosaurs and is still among us.

This article originally appeared in our February 2018 issue.