Civil War reenactments have long been popular in the South, and they may grow more so as we approach the 150th anniversary of the conflict.

Could I Do It Feature

What might a new Confederate soldier have faced at New Market, Virginia, on May 15, 1864, when roughly 6,300 Union soldiers and 4,500 Confederate troops engaged in a fierce battle? My account of a young soldier’s first combat experience is not solely a product of my imagination; it was based on my participation in a reenactment of the actual Battle of New Market, in which the Confederates defeated the Union army and, in doing so, dealt a blow to the North’s strategy of taking control of the Shenandoah Valley.

At New Market, both Confederate Gen. John C. Breckinridge and Union Gen. Franz Sigel aimed to occupy the high ground. Outnumbered, Breckinridge expected to be attacked at his position on Shirley’s Hill. When that didn’t happen, Breckinridge, rather than wait for Sigel to be reinforced, attacked Sigel by rushing north to the area were the Union line had formed in the middle of Sarah and Jacob Bushong’s farm. “We can attack and whip them here, and we will do it,” Breckinridge bellowed at one point prior to the engagement, according to the book The Battle of New Market, by Joseph W. A. Whitehorne.

The battle was marked by lots of artillery fire and heavy rain. At one point, according to historical accounts, a Union shell blew a hole in the center of the Confederate line. Roughly 250 VMI cadets, most between ages 17 and 21, rushed in to fill the gap. They helped to repulse a Union charge, then swept forward with the other Confederate troops in a counter attack. The Union army retreated along the old Valley Turnpike to Mount Jackson. The cadets later named the muddy battlefield the Field of Lost Shoes, because so many boots were sucked off their feet in the muck. Union casualties (dead and wounded) were estimated to total 840 compared to 540 for the Confederacy.

The New Market reenactment, one of dozens of Civil War-related events held in the U.S. every year (including at least a half dozen in Virginia), took place this year on May 15. According to Scott Harris, who runs the New Market Battlefield Museum, 1,150 people took part, playing roles as Confederate and Union soldiers and officers, and nearly 3,000 spectators watched.

Why do people take part in reenactments? Most of the participants have a serious interest in the Civil War and say that taking part in a battle re-creation helps to put a flesh-and-bones perspective on events otherwise relegated to history books. “One of my favorite hobbies is reading, especially historical books,” says Marc Ramsey, owner of Owens and Ramsey Booksellers in Richmond and a reenactor for 14 years. “Reenacting allows me, in a manner of speaking, to go back to that time I read about. When I read about a Union regiment trying to outflank a Confederate regiment, I know what it actually looks like. When I read about artillery fire, I have a better idea what it sounded like.” Beyond that, he enjoys the camaraderie of the people—“sleeping under the stars with a crackling fire nearby. So many people with diverse backgrounds, all enjoying the same experience.”

Ramsey expects the war’s 150th anniversary, beginning next year, to spike interest in reenactments. “I’m seeing younger people joining this hobby this year,” he says. “And we’re getting a number of ex-military people who’ve come from Iraq and Afghanistan and want to be a part of this, as well.”

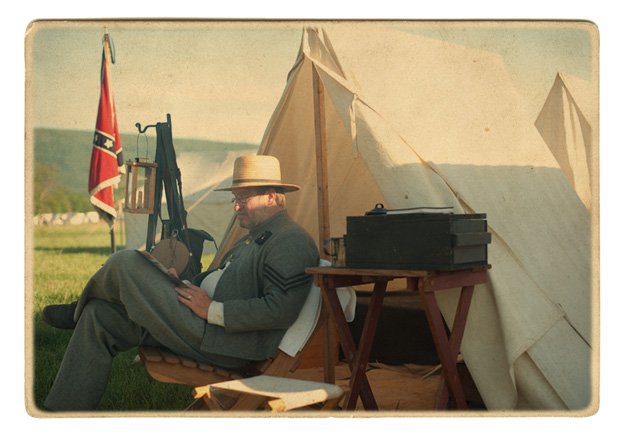

Ramsey explains that there are three types of reenactors and events. The first, “mainstream,” is by far the most popular. Its participants live in tents, set up their camps and strive to create an authentic Civil War scene. Though some of the “soldiers” might bring along coolers and cell phones, they are vigilant about keeping them out of view. “Some will have their children participate so it can be a real family thing,” he adds. New Market was a mainstream reenactment.

The second category is “campaigners,” individuals who take the Civil War experience one step further. They arrive with everything they will use that weekend in a knapsack and haversack, including all food, bedroll and blanket, a drinking cup and extra clothing. They do not go back to the car for shelter in a storm or for a clean shirt. They sleep in the open, not in a tent. Campaigners are all about getting close to the true life of a Civil War soldier. Some events even have no spectators. Campaigners might hike five or 10 miles to reach the event site. It is all about living the ancestral experience.

The third group is described, appropriately, as “hard-core.” These are people who try to become 19th-century people and soldiers. They will only eat what was available to the soldiers in the Civil War—meaning that they will make hardtack, on-site, and then eat it. They wear clothing that is an exactly replica of the clothes worn in, say, the 1860s, even matching the stitch count.

Although most reenactment groups welcome new “recruits,” don’t arrive in a uniform rented from a costume store. That is akin to wearing wingtips and black socks to a pool party. Novice reenactors are allowed a certain amount of “farbishness” (inauthenticity) but not for long.

Becoming a reenactor is not cheap. You must buy a gun, uniform, bayonet, hats and all the accoutrements, including canteen and cartridge belt. Ramsey says it took him five years to get a full kit. Buying all new authentic clothing could cost $1,200, not including gun and camp accessories. There are a sizeable number of businesses throughout the United States, usually called sutlers, that supply clothes and accessories to period reenactors. Many go to Civil War events to sell gear and paraphernalia to both reenactors and spectators.

As a rookie reenactor, I was able to borrow gear from other New Market participants. My Confederate military garb consisted of a wool kepi (hat), a wool shell jacket, wool pants (held up by suspenders), a rubber poncho that would also act as my ground matt for sleeping, and a haversack, which contained a few ditty bags and some string. I was also given a pair of typical Civil War boots, with only a leather or wooden sole and a steel heel plate. For troops who often traveled 20 miles a day on foot, those boots must have been sheer torture.

Scott Williams, a geographic information systems analyst and a reenactor for nine years, helped to turn me into an adequate Confederate soldier. He showed me how to operate the Springfield rifle and rehearsed me on the drills we performed on the day of the battle, including Shoulder Arms and Fix Bayonet. On event weekends, Williams is a private in the 15th Virginia Volunteers—a group he chose because he had ancestors who were members of the 15th during the 1860s, and also because “they are very dedicated to doing an accurate portrayal of a Confederate soldier.”

Williams, like Ramsey, is a campaigner who believes that role playing heightens one’s knowledge of the war. “I can visualize a lot better what these soldiers may have gone through,” he says. “I can smell the fires, feel how hot or cold they must have been, and to some degree know a little of their hunger and discomfort. You know that each soldier knew this might be his last day on earth, and for a great many it was.” He adds, “When you visit historical battlefields and look at the open ground [the] men on both sides had to cross under heavy fire, you ask yourself, ‘Could or would I do it?’”