Summer is time for camp, and in Virginia, that tradition is as strong today as it was 100 years ago. A look at the enduring appeal of sunlit days and lake swims, archery and riding, cabin pranks and rousing choruses of “Little Bunny Foo Foo.”

Girls enjoying the Camp Mont Shenandoah’s swimming hole today.

Ann Warner, director of Camp Mont Shenandoah, with Rollins and Otis.Ann Warner, director of Camp Mont Shenandoah, with Rollins and Otis.

Campers at Westview on the James in Goochland enjoy water sports in the river, including a zip line.

Kids at St. George’s camp can see into the Shenandoah Valley.

Cabin life at Camp Mont Shenandoah in the 1970s.

Matthew Richardson, interim director of Camp River’s Bend.

In 2015, there are a lot of ways to go to camp. There is sports camp, math camp, drama camp, chess camp, cooking camp, farm camp, photography camp, space camp, yoga camp, engineering camp, hip-hop camp, circus camp, cartooning camp and SAT prep camp.In short, if it interests your kid, there’s probably a camp for it.

But long before before all that, there was: camp.

You know this camp, even if you’ve never attended one. It is Norman Rockwell iconic. It is archery and arts and crafts. Campfire circles and sing-alongs. Canoeing and cold-water swimming. Sleeping eight, 10, 15 to a one-room cabin with screens for windows and a single lantern or bare bulb casting crazy shadows overhead. Letters home dutifully scribed on rainy afternoons, flopped belly-down on a wooden bunk.

And in the 21st century, this camp is still surprisingly alive and well. Despite the seductive attractions and comforts of the Xbox and air conditioning, Snapchat and Chipotle, nevertheless a cohort of the instant-everything Internet generation still willingly—indeed enthusiastically—trades all that for two, three, six weeks in the woods: modern-day Thoreaus with orthodontia and ponytails, embracing rustic living, archaic entertainments and a litany of traditions so long-established and revered that the most modern, selfie-snapping teenager can recite them with shining eyes, a catch in the voice and not so much as a whisper of irony.

At Camp Mont Shenandoah on a brightly lit early spring day, it’s decidedly the off-season. A thick, crusted-over layer of snow crunches underfoot as Ann Warner, the camp’s director and co-owner, strides the Bath County camp’s property. Her dogs, Rollins and Otis, gambol happily around her, the sun shines through trees still bare of leaves and the Cowpasture River murmurs past, swollen with snowmelt. Since 1927, Camp Mont Shenandoah has occupied this property on a gentle bend of the river; generations of girls have plunged shrieking into the swimming hole (“No one’s allowed to say it’s cold: it’s ‘brisk,’” says Warner), performed musicals on the rough stage of West Lodge, chattered over family-style meals in the Feed Bag, gathered around the fire circle, and hunkered down in cabin bunk beds to giggle with friends before drifting to sleep to the night sounds just beyond their screen windows.

The privately owned camp has been in Warner’s family for some 65 years, since her grandmother became a co-owner with several other partners around 1950. Her grandmother helped run the camp in a variety of roles until 1966, when she passed her ownership share to her daughter, Warner’s mother. Ann and her sister were both Camp Mont Shenandoah campers in the 1970s, and Ann also worked as a counselor there. After attending Hollins College, however, Ann moved to Northern Virginia. She saw herself, she says, as a “bright lights, big city girl,” someone who wanted to be in the busy heart of things. But when the other owners wanted to sell in 1994, the city girl surprised herself. This year will mark Warner’s 19th summer as co-owner (with her mother) and director, and the 29th she has spent at Camp Mont Shenandoah.

“If you had told me, back when I was at Hollins, that this is what I would be doing now, I would have said ‘No way!’” says Warner. “But I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

Many CMS campers, like Warner, have mothers, sisters, grandmothers and cousins who have also attended; Warner is now starting to welcome girls whose mothers were campers when Warner first assumed the role of director. And if you don’t count the modern infirmary building being constructed to open for the 2015 season, almost nothing about the camp today would have appeared out of place when those mothers and grandmothers were donning “whites and ties” (still the uniform for special occasions), practicing their archery skills and competing as a “Green” or a “Buff” (one of the camp’s oldest continuing traditions) years and decades and more in the past. (In December, Camp Mont Shenandoah was listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register, and in April it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.)

Cabin life at Camp Mont Shenandoah in the 1970s,

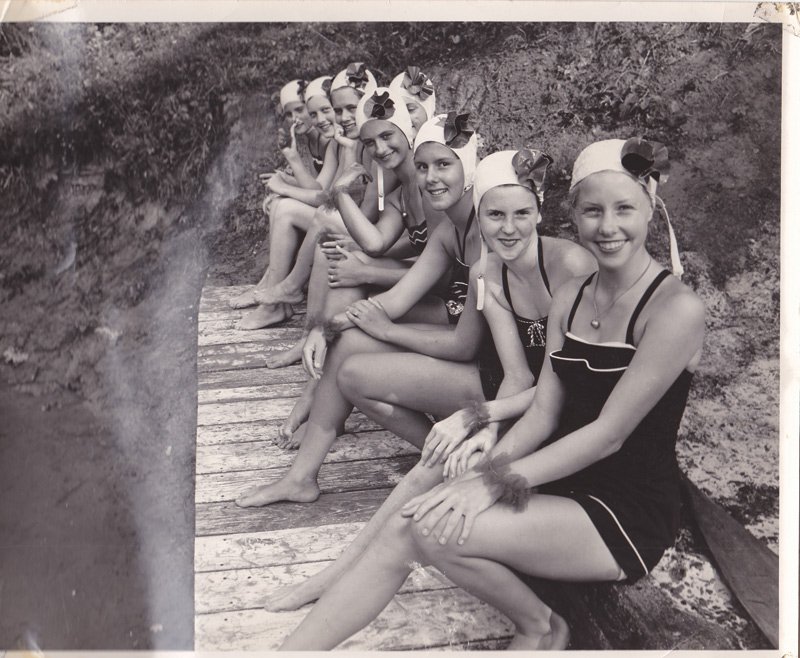

Swimmers of yesteryear at Camp Mont Shenandoah.

Camp Mont Shenandoah.

Campers pose for a group picture.

Girls enjoying Camp Mont Shenandoah’s swimming hole in its early years

Welcome to camp.

Canoeing on the lake.

Arts and crafts projects.

The traditional sleep-away summer camp is a peculiarly American institution with a history reaching back to the second half of the 19th century. Made possible by the long summer vacations of American schools, it was born, according to historians of the camping movement, out of a blend of romanticism and anxiety that strikingly mirrors the concerns and longings of many of today’s parents. It was a time of “technological upheaval,” writes Leslie Paris in Children’s Nature, her history of the rise of the camping movement, with “new technologies and commercial markets that were transforming the American economy,” while immigration and rapid urbanization seemed to be doing the same to its national character. The “rate of change—indeed a culture of change—appeared to be intensifying rapidly,” writes Paris, and “many adults feared that something vital had been lost in the transition: a familiarity with the natural world, a slower pace, rootedness in the land.”

At the same time, parents and public figures fretted that the ease of modern life and the long summer vacations free of the improving influence of organized education would render the nation’s young people “bored, listless, and susceptible to unsavory influences”—idling wastrels incapable of sentence composition or survival.

Camp was the antidote. Camp founders criticized “the ‘artificiality’ and ‘speeded-up’ pace of contemporary life,” writes Paris, and promised to reinvigorate their young charges with fresh air, good food, bucolic scenery and a program of deliberately anti-modern amenities and diversions that even then traded on nostalgia for a mythologized past. Paris quotes a brochure from a boys’ camp offering assurance that “camping is not a vacation of idleness and trivial pleasures but an institution to teach the child to employ the leisure of its entire life in a healthful, cultural, and constructive manner.”

Though camp was devised as an “Arcadian fantasy,” in Paris’ words, under the regulation and supervision of adults, somehow—for many children then and now—camp has nevertheless been experienced as a joyful interlude of freedom and independence, of fierce and enduring friendships, of inside jokes and outside adventures, and of inner confidence born of facing challenges and choices all on your own. You can talk to adults whose own children are long grown who will tell you that some of their closest friends, dearest memories and most foundational experiences all date back to summers at camp. Camp, says Ann Warner, is a safe space where kids can take risks and learn to be themselves. “It’s a place,” she says, “where you can let your own light shine.”

Betsy Peyton attended coed St. George’s camp in Orkney Springs (a 19th-century resort destination) during the 1970s and ’80s. Today she lives in Manhattan with her husband, Will—whom she met at camp when they were 11 and 12 years old. Will actually served as director of the 53-year-old camp (which is operated by the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia) for several years, and all three of the couple’s children attended St. George’s as well. Their shared memories are of capture the flag and tripping over tree roots at night, of campfires and sing-alongs, of comforting a homesick cabin-mate, of rope swings and silly pranks (bras up the flagpole; 100 campers cramming, clown-car style, into a single cabin to confound counselors searching for them; staff hiding counselors’ cars “in places you wouldn’t have thought it possible to drive to”) and, says Betsy, of “cute counselors with guitars and long hair” (that would be Will).

Ashley Tremper, who teaches Latin at Trinity Episcopal School in Richmond, was a camper for a few years during elementary and middle school at Westview on the James in Goochland, which was established in 1966 and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church. Their cabins, she recalls, were essentially screen porches with bunk beds and roofs. They ate family-style in the mess hall and spent a night sleeping out in the wilderness. “We dug our own latrines. For a sixth grader, it was a little daunting,” says Tremper. But when she looks back, what she remembers most are the friends she made and “being away from home, and the freedom to make my own decisions.” They were hardly monumental: She distinctly remembers the thrill of selecting a bag of Skittles at the camp store. But those choices were hers alone.

That sense of responsibility, says Ann Warner, is a big part of what makes camp valuable for kids. For the youngest, accomplishment and pride are born of simply navigating successfully through the day with no parents nearby: conquering homesickness, finding their way from the mess hall to the riding stables, keeping track of t-shirts and swim goggles and hair scrunchies. As children grow older and begin to navigate the rocky shoals of the hormonal years, camp can be a steadying place that helps them form a strong core of self.

Camp is also a place for encountering nature; even in the 19th century, camp was pitched as a bracing counterbalance to sissified, citified living, and today, in an era when many children rarely have the chance to venture past manicured suburban lawnscapes, camp offers generous helpings of fresh air and rustling leaves, crickets in the night and outdoor play. And sometimes a little more.

Betsy Peyton worked as camp nurse at St. George’s for a few summers and remembers the year that a pack of boys on a post-dinner scavenger hunt stumbled into a nest of infamously short-tempered yellow jackets. Howling and screaming, says Peyton, the boys tumbled en-masse into her infirmary, still chased by the angry hive. Fortunately, there were no allergies among the victims, says Peyton, but it was a scene of mayhem, with “hysterical children lying on the floor, sobbing and swelling with angry red welts.”

And one summer at Camp Mont Shenandoah, recalls CMS alumna and former counselor Catharine Robertson, a first-year counselor calmly responded to a crisis in the Feed Bag (the camp mess hall) climbing onto one of the long tables, snatching down a snake dangling from the rafters, and marching out the door to fling it into the woods. “It was legend!” says Robertson.

Testing boundaries is also a time-honored tradition for older campers. Warner recalls a summer several years ago when “a group of 14 older girls had a thing for sneaking out of their cabin at night and ‘streaking’ around camp.” Finally caught in the act as they tried to make a run through another cabin of sleeping girls, “they, of course, had a stern talking-to about how they weren’t setting a good example, etc., etc.,” says Warner. (A few nights later, the other cabin retaliated by doing some streaking of their own.)

“Sneaking out of your cabin in the middle of the night feels like you’re doing something really scandalous, even though you are really not doing anything at all,” says Sarah Mellen, a junior studying history at James Madison University and a “lifer” at Camp Mont Shenandoah. Mellen started at the camp as a 7-year-old, then graduated to counselor-in-training and eventually to counselor, the role she’ll return to this summer. Although Mellen’s home is in Millboro, only a few minutes from Camp Mont Shenandoah, she says that once she arrived at camp each summer, she was in a different world: “It might have been states or whole countries away from home, and I wouldn’t have known the difference.” Camp, says Mellen, “has been a driving factor in how I have made the decisions in my life. It has shaped me as a person and is such a huge part of who I am.”

The reliable traditions—along with the valuable lesson of “learning to live away from home and learning to live with other people and making friendships away from my family”—are what Maria Holt Elder of Richmond says she loved about 86-year-old all-girls Camp Strawderman in Edinburg, which she attended between the ages of 13 and 15. Her daughter Sherwood was a camper there around the same age. “Sherwood did exactly the same things I did,” she says. “Same schedule, same activities, same songs, same dinner hikes.” On Sundays, she says, girls would wear a uniform including white canvas sneakers; when Maria was a camper, the girls had to whiten their shoes with polish. When Maria picked Sherwood up at the end of her first two-week summer session, “she was so excited to tell me that she had found my name written in white shoe polish in the rafters of the cabin she lived in.”

Matthew Richardson, a seventh grade history teacher and a running coach at Collegiate School in Richmond, comes from a camp family, too. His grandfather, father, uncles and older brother attended the all-boys Camp Virginia in Goshen, which was founded in 1928. “So when I was eight years old and had the opportunity to go, I was so excited,” he says. “A lot of the people I am closest with to this day are my camp friends. Through my life, the people I can always count on to be there are the people I went to camp with.”

Richardson, who is now in his mid-20s, calls his camping days “transformative.” A kid who struggled with attention problems in school, he found himself a leader at camp. “If it was ‘who could ride a horse?’ or build a fire or climb, these were things I knew I was good at and were things I could help others find success with, and through those things I knew I could be a leader,” he says.

Camp Mont Shenandoah.

Camp Mont Shenandoah.

Horseback riding is a camp tradition.

Inside a cabin.

Explorers’ Camp.

Early campers.

Wortie Ferrell, who was a counselor at Camp Virginia for 14 years during high school, college, and his early years as a middle-school teacher, loved the pace of life at camp, the camaraderie among the counselors, and the laughter, which “weaved through everything.” Sure, it was sometimes a challenge to get pre-adolescent boys to remember such niceties as actually changing into a fresh shirt at some point during their camp weeks, but his memories are of competing cheers in the mess hall on the annual July Fourth orange vs. black competition, the ample unstructured time “when boys could get together and generate their own fun,” and every night at the end of the evening, Perry Como singing the “Lord’s Prayer,” broadcast over the loudspeakers.

Those are the kinds of traditions Matthew Richardson hopes to see grow organically at the newly created Camp River’s Bend, an all-boys camp situated on the Cowpasture River, not far from Camp Mont Shenandoah. Richardson will serve this summer as interim director of the camp, which is backed by a founding community, including an advisory board and the owners of the property where the camp will be located, all of whom are passionately committed to the traditional camp experience. Camp River’s Bend’s inaugural summer was fully subscribed, with a waiting list, almost as soon as applications were made available in February—before even a single cabin was built. “I think this is something that a lot of kids are hungry for,” says Richardson.

Camp River’s Bend will prove an interesting experiment: Can tradition be built from scratch? The first summer will offer a single, three-week session for experienced campers ages nine to 15. Days and evenings will be filled with the usual camp experiences—swimming and canoeing, hiking, campfires, sports, games. However, part of each morning will also be devoted to a unique endeavor: letting the campers themselves help to create the founding traditions of the community.

“The values of loyalty and respect and responsibility, of being trustworthy and true to your word, of accountability and leadership and having each other’s back—all those things that resonate as what I learned at camp, those are the values I want to see transferred to Camp River’s Bend,” says Richardson. “People who think a place like Camp River’s Bend is about camping or archery or canoeing don’t get it,” he adds. “What a place like this is about is the relationships, the people, the values and, most importantly, the camp family that grows out of that joint experience.”

Ann Warner agrees that these nearly ineffable qualities, so hard to describe to an outsider, are what make camps like Camp Mont Shenandoah, which also maintains a waiting list, endure. Warner has watched shy and snaggle-toothed seven-year-olds transformed, summer after summer.

“The greatest reward,” she says, “is watching these girls grow into strong, capable young women, with the confidence to do anything they want.”

For more information on the camps in this article, use the resources below:

Camp Mont Shenandoah

Millboro Springs

CampMontShenandoah.com, 540-997-5994

Camp Strawderman

Edinburg

CampStrawderman.com, 301-868-1905

St. George’s/Shrine Mont Camps

Orkney Springs

ShrineMontCamps.net, 804-643-8451

Camp River’s Bend

Millboro Springs

CampRiversBend.org, 804-314-6656

Westview on the James

Goochland

WestviewOnTheJames.org, 804-457-4210