Tea is enjoying a rebirth, and no place can it be seen more easily than in Nepal. Riding up high to tea plantations on Buddha Air, Susan G. Hauser finds that India is no longer the last word on tea.

A tea plucker

Tea fields

Gen. Pande

Suraj’s garden

The flight attendant tottered down the aisle passing out plastic cups to the 20 passengers traveling from Katmandu to eastern Nepal. Then she tucked a two-liter plastic bottle under one arm and deftly poured us drinks. With the Himalayas somewhere to the north, Buddha Air couldn’t have picked a better in-flight beverage: Mountain Dew.

Unfortunately, there was no mountain view to go with the Mountain Dew. Monsoon season had just begun in Nepal, bringing clouds and occasional downpours. Outside the propjet’s windows, gray clouds blanketed the earth, including its highest point. We knew Mount Everest was out there somewhere. But with the monsoon, no one expected to get more than a glimpse of the Himalayas for the rest of the summer.

Monsoon season meant little to my traveling companions, a couple of tea men from my hometown of Portland, Oregon. Buyers for Tazo Tea, they set their clocks to a different cycle of nature. To them, this was the height of second flush.

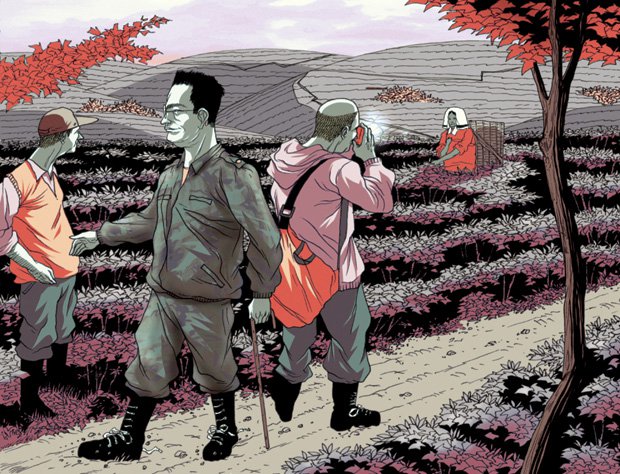

In tea terms, a flush has nothing to do with either fevers or toilets. It means a period of new growth of the tender top leaves of the tea bush. In high mountain regions such as eastern Nepal, a flush generally lasts about a month and a half. That’s when women pluckers in colorful garb snake through acres of waist-high tea bushes, breaking off the very tip of each branch—namely the top bud and the next two leaves—and dropping it into bamboo baskets carried on their backs.

Steve Smith, the founder of Tazo Tea, and Tony Tellin, his assistant tea buyer, were sampling the teas of Nepal for the first time. Ordinarily, their destination in the Himalayan foothills would be neighboring Darjeeling, India, where Smith has been buying tea for some 20 years. But the tea growers of Nepal, where the 150-year-old industry has recently been revived after a long period of stagnation, were eager to show off their wares.

After the Buddha Air flight touched down in Biratnagar, we were met by Suraj Vaidya, a successful businessman from Katmandu. Vaidya’s pedigree was impressive: Son of a business leader, his cousin was the late Tanzing Norgay, the famous Sherpa who led Sir Edmund Hillary up Mount Everest. Married to a former Miss India, Vaidya is at age 43 the president of Guranse Tea, a pioneer in the Nepalese tea renaissance.

On top of all that, he is the Toyota dealer for all of Nepal, so he had a brand-new Toyota van waiting to carry us over winding mountain roads to Guranse Tea, where acres of lush, green tea bushes dot the steep hillsides. Vaidya took us on a tour of the tea processing plant, where freshly plucked tea leaves are dried, rolled and fired in a low oven before being packed and shipped. We each were given a package of Guranse tea as a souvenir.

In the morning we took a walk through a portion of the “garden,” as tea plantations are called. Afterward, Vaidya cautioned us to check our shoes for small leeches, the bane of tea pluckers. We took a cursory glance and then hurried off to breakfast at the neighboring army base with Brigadier General Pawan Pande, Vaidya’s good friend.

General Pande, carrying a swagger stick and looking dapper in camo and combat boots, offered us pancakes, sliced mango and tasty local foods. After breakfast, he reminisced with Vaidya about their several sojourns in America, discussing the relative merits of L.A. and New York City. Then Vaidya’s deep voice grew even huskier with sweet sentiment.

“I miss Virginia,” he sighed. “To me, Virginia is the most beautiful state in America.”

He explained that he had been a graduate student at George Mason University in Fairfax, studying international business from 1982 to 1984. The experience had meant so much to him that when he looked out on the foothills of the Himalayas, he longed for the rolling hills of Virginia.

But this sentimental sighing ended abruptly when Vaidya spotted a sated leech lolling on the carpet. This time he advised us all to check our legs. Steve Smith promptly discovered a bloody bite on his calf. I pulled up my pants leg and screamed. My once-white sock was now bright red.

As I yanked off my right shoe and sock, Gen. Pande sprinted to his private quarters. He returned holding a small bottle. I held up my foot and he gallantly sprayed the wound. I glanced at the bottle’s label, just catching the words “Pour l’homme.”

Now when I drink my souvenir tea from Nepal I long for the foothills of the Himalayas. The scar of a leech bite is my special souvenir, along with the memory of the day my foot smelled like the face of a general in the Royal Nepalese Army.

—Originally Published August 2006

Info on Buddha Air is at BuddhaAir.com. Visa applications are at NepalEmbassyUSA.org.