Take a midday spring stroll through Virginia Beach’s First Landing State Park and you might happen upon a heartwarming sight: A group of about a dozen children aged 3 to 6 snoozing in a motley array of sleeping bags and hammocks beneath a canopy of live oaks, dripping with Spanish moss.

The Lost–Boys–esque tableau repeats in public lands or farms around the city on most weekdays throughout the year. But these aren’t responsibility-flaunting truants—they’re young learners enrolled in the Organic Beginnings Montessori Forest School. The program takes the classroom outside, rain or shine, and instructors blend pre-prepared lessons with place-based inspiration to help kids guide their own learning.

“It’s about getting children into nature and creating a supportive space where their innate curiosity about the world and desire to learn through play can blossom,” says school owner, Marie Weaver, a certified Montessori Association Internationale instructor who holds a master’s in education from Loyola University Maryland.

Monday, for instance, may find learners hiking through sandy woodlands in Cape Fear State Park, building stick shelters, observing bugs, or playing in the splayed limbs of a live oak. Instructors steer attention toward nifty forest features, offer related insights, and encourage kids to explore whatever piques their interest. They field questions as they come—like, ‘What kind of bird is that?’—and help pupils use reference materials, including field guides, encyclopedias, or the Internet to find answers. The kids share sensory perceptions around objects or activities and feelings evoked by their experiences in guided group discussions.

Over time, the approach “grounds kids in and helps inspire a lifelong appreciation of nature,” says Weaver. It also fuels holistic growth around skills like “creative problem solving, social awareness, emotional regulation, grit, and self-confidence.”

All of which, says Weaver, is linked to better overall mental and physical wellbeing later in life. And she’s not alone in the assertion. A recent deluge of scientific literature has shown the benefits—even necessity—of spending time outdoors for people of all ages, inspiring more and more schools to incorporate nature-based programming into their curriculum.

“At this point, the evidence is overwhelming,” says Dr. Meredith Hayden, University of Virginia’s student health and wellness chief medical officer. Regular engagement with nature can positively impact “so many dimensions of our well-being—from mental, to intellectual, physical, and even creative.”

That’s why Hayden has spent the past four years working with university medical colleagues to harness those benefits for students. Clinicians at UVA’s student health office now write “nature prescriptions” for activities like hiking to help alleviate issues that include stress, mood imbalances, and anxiety. There’s also a full-credit course at the university called “Engaging With Nature,” which explores various nature practices and their positive effects on wellbeing.

The course is team-taught by Hayden and other UVA medical professionals. Classes meet at nature spaces on or around campus and each instructor covers a specific practice. Forest bathing sessions, for example, may carry students to trails in Shenandoah National Park for a series of silent pauses to observe flora, fauna, sounds, and their own bodily sensations. The experience is followed by discussions about post-walk feelings and causal effects like lowered blood pressure and heightened levels of endorphins. “The goal is to introduce students to an extremely effective [way to self-regulate],” says Hayden. “We hope they’ll incorporate nature practices into their routines moving forward and enjoy happier, healthier lives because of it.”

The Waynesboro Public Schools Education Farm has similar goals. The .75-acre facility launched in 2021 and now provides more than 3,000 lessons a semester to students across all grade levels, including pre-K. Lead farm educator Ryan Blosser works with teachers to craft lesson plans that reinforce classroom studies with hands-on experiences.

“Our primary objective is to use what’s happening on the farm to create core memories that students can use for recall around standards of learning,” says Blosser, who holds a master’s in clinical mental health counseling with an emphasis on nature-based therapy from James Madison University and is a co-founder of the Shenandoah Permaculture Institute.

Fifth-grade science classes harvest ripe herbs and veggies, then craft a salsa “mixture” and hot sauce “solution” in an outdoor kitchen. Third graders studying simple machines load pumpkins into wheelbarrows and compete in relay races. High school economics students gain small business experience managing a working farm produce stand. Kids reap the benefits of being outside and engaging with nature along the way.

“It’s a win-win, no matter how you look at it,” says Blosser. Kids are introduced to an alternative learning method while building household skills and nutritional literacy. Test scores and academic performance have improved among most participants. And teachers say kids return from the sessions calmer and more attentive.

If done right, says Hayden “incorporating nature experiences into educational curriculum is beneficial for everyone involved.”

And what’s more: Those benefits pay dividends across a lifetime.

The Nature Connection

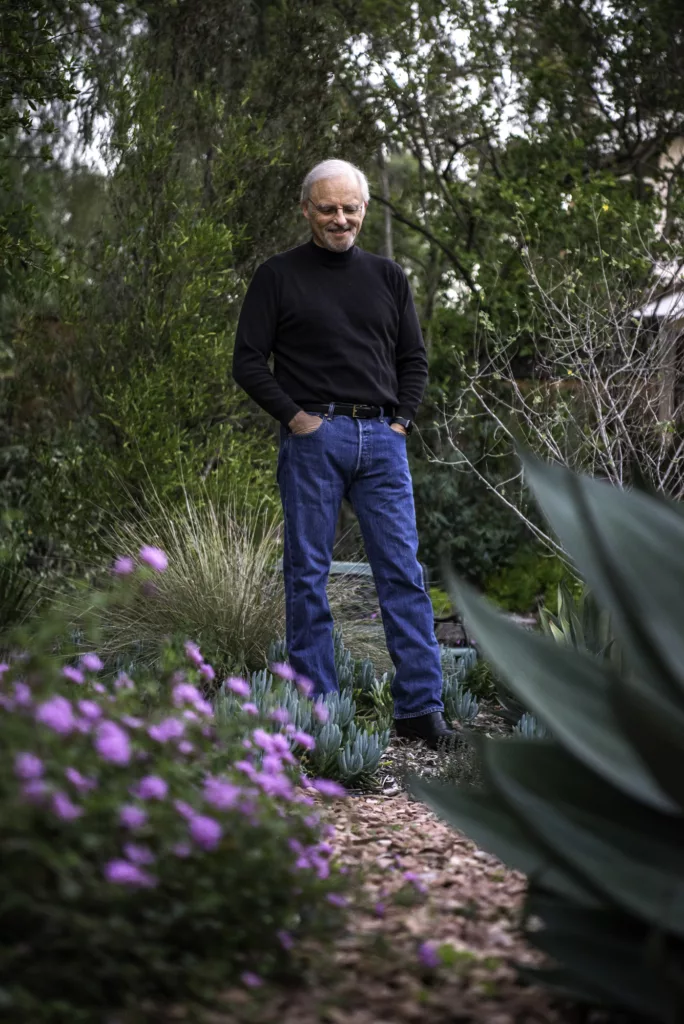

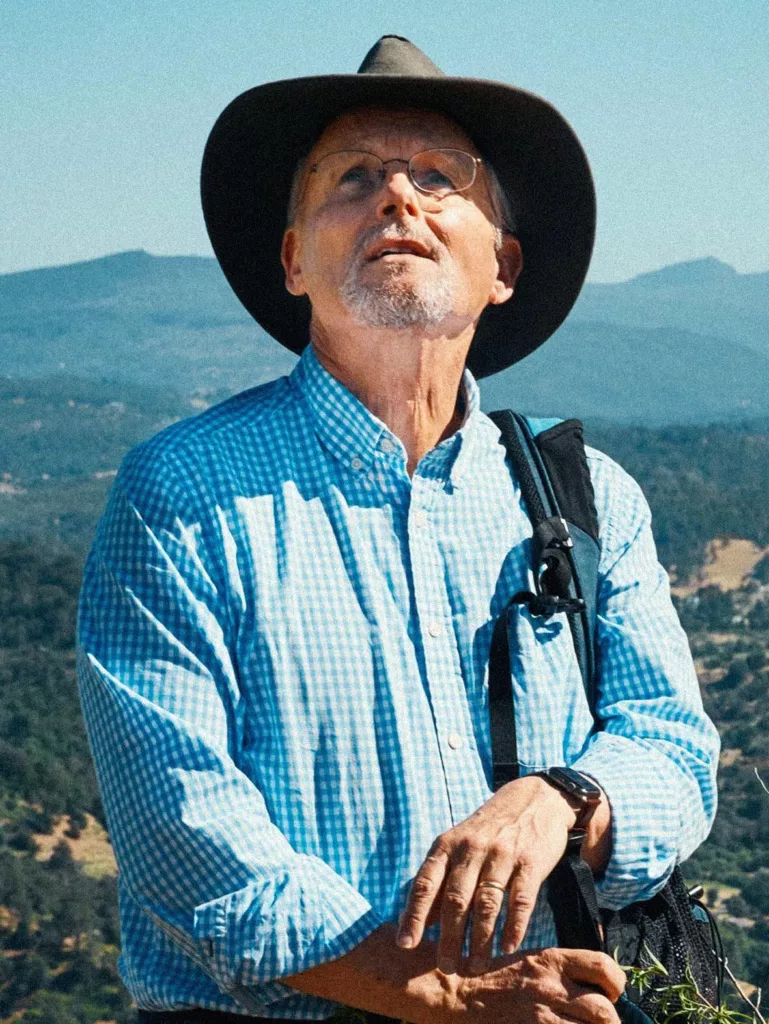

Richard Louv sees a world where children and nature have drifted apart. From his home in the mountains of Southern California, this bestselling author has sparked an international conversation about reconnecting people—especially kids—with the outdoor world.

In his groundbreaking book, Last Child in the Woods, Louv coined the term “nature deficit disorder” to describe this growing disconnect. As children spend more time with screens and less time outdoors, he points to concerning trends in physical and mental health—from increasing rates of obesity and depression to attention challenges.

The beauty of Louv’s message lies in its simplicity: in our tech-focused world, the path to wellbeing might just lead through the garden, the park, or the nearest patch of wilderness. Because in Louv’s vision, reconnecting with the natural world isn’t just about fresh air and exercise—it’s about rediscovering what makes us fundamentally human.

—by Madeline Mayhood

This article originally appeared in the April 2025 issue.