How birds can teach us to look at the world differently and other observations.

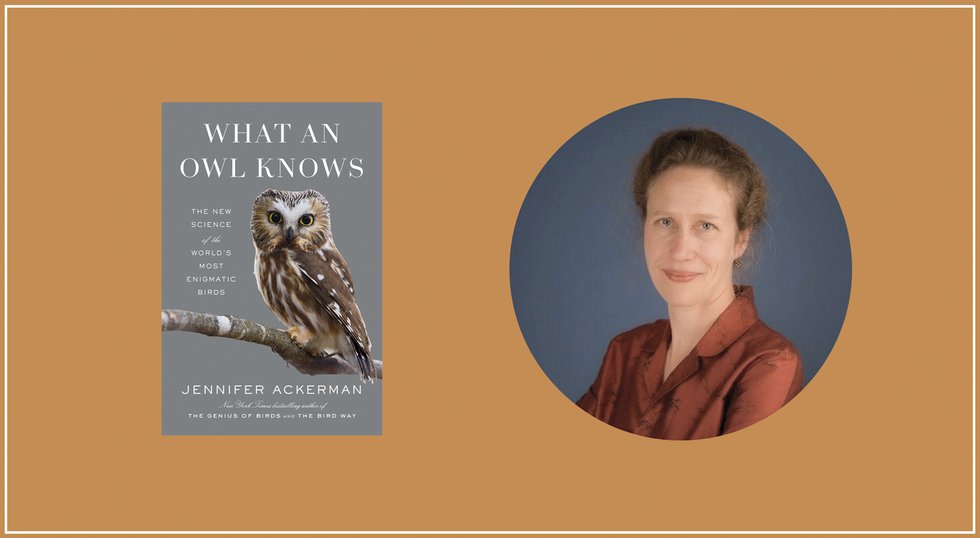

What An Owl Knows by Jennifer Ackerman. Penguin Press. pp.352. $30.

New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Ackerman’s newest book illuminates the vibrant history and wonders of these nocturnal beauties. She joins research scientists, investigating how owls communicate, hunt, court, and just live in this changing world. Where some live in underground burrows, others prefer to roost in large groups, and where many dine on rodents and other birds, some must live on black widows and scorpions.

Ackerman curates all this fascinating research, making it breathe with life through her own observations about owls, further examining why these birds beguile us so. What An Owl Knows is a terrific and joyful look at owls across the globe and throughout history. With fluid prose, she delivers an intriguing account of their amazing hunting prowess, their unique vocalization skills, and overall supernal sensory abilities. What An Owl Knows translates the scientific lingo and data research on owls into a careful and spellbinding narrative for a brilliant book on one of the most enigmatic denizens in the bird kingdom.

Konstantin Rega: Your three previous books are also about birds. Where did this bird fervor come from?

Jennifer Ackerman: I’ve loved birds since I was a child. I went birdwatching with my dad in Washington, D.C. on the C&O Canal. He really inspired this passion. My first book was Birds by the Shore, looking at the nature of the Mid-Atlantic coast. Then I took a kind of detour into human biology, but I’ve come back around to birds. They’re really my first love.

I wanted to figure out how birds communicate, why they sing, how they learn their songs, and whether what’s going on in their mind doing their daily activities. And that got me writing The Genius of Birds and also The Bird Way. From there, I wanted to do something about owls.

Owls are just so unique in the bird world. They’re night hunters, and so have these extraordinary senses. When I started to think about writing a book about owls, it just made my head sizzle with questions. You know? Like, what makes an owl an owl? How did they get to be the way they are?

And they have this reputation for being, “wise birds,” but are they actually? We’ve been studying them for a long time, but only lately, have there been the technological breakthroughs necessary to solve some of the mysteries that have been around for centuries. So it was a very good time to write the book.

So you’ve been writing for 35 years. When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

I loved writing as a kid. And, you know, I wrote really bad poetry and little stories. I was an English major in college. And then I just got interested in this idea of being a translator for the world of science and, and I’ve never looked back. I really enjoyed every minute of it. And I feel very lucky to be living and working this way.

So while doing all this research on owls, what most surprised you about them?

Oh, so many things. We think that owls just have hooting, but some new research suggests they have all different kinds of vocalizations that are used in very specific ways in different contexts. Great horned owls have 15 different vocalizations—six kinds of hoots, four types of chitters, and five kinds of squawks. They also have very individual voices, and a kind of signature hoot used to identify one another.

And, you know, we think of humans as the pinnacle, but we’re not in many ways. For instance, a great gray owl can hear a vole under a foot and a half of snow while hovering high in the air. There are close to 260 species worldwide, and they just vary tremendously. The biggest is a Blakiston fish owl—it’s very rare bird and about the size of a fire hydrant. And then we get one like the elf owl, which is smaller than a pine cone.

What is your role as the writer? How do you want to show the world what you’ve learned?

I’m a sort of intermediary between the scientist and the layperson. I love translating the sometimes tricky science-speak into interesting stories and narratives.

And so for this book, I talked with experts all around the world, and I spent time in the field with some of the best. And then I spoke with specialists working with captive owls, to heal them or to train them as animal ambassadors. Those are the people who are sort of teasing apart the mysteries about owls—their individuality and personality, their emotions and intelligence.

In fact, I went to the Wildlife Center in Virginia and spoke with people there, met some of their ambassador owls and really learned a lot about what they’re discovering about these birds through working with them up close, one-on-one.

And what do you want readers to get out of this book?

You know, I wanted people to see owls with a new curiosity and awe. To see them as these really subtle, idiosyncratic, ingenious, and fascinating creatures. I wanted to show how owls might be showing us different ways of knowing, of being in the world. So I really hope people will come away caring more about their survival and doing whatever they can to help—working on owl conservation, just being more aware on the whole.

Studying these creatures, I’ve learned how we might move through life a little bit more quietly. They’ve taught me how to center myself so that I can better notice sights and sounds that might have otherwise gone unnoticed.

Get a copy at The Bookshop.