A remarkable mammal with an apt name

What is this gift that the cat has left on the front walk? It’s a cute, furry little guy. And it was nice of her to stop at simply mauling him to death and leave him intact. Is it a mole? Maybe … its eyes and ears are barely visible, and its snout is a little long, but moles are rounder, with big, spadelike claws for digging. Vole? Nah—this specimen has small, pointy teeth rather than long rodent-y incisors, and voles have longer tails.

The gift is a shrew, most likely a northern short-tailed shrew, Blarina brevicauda, one of 30 shrew species found in the U.S. Not only is it not a vole—this little insectivore is not even a rodent. And there’s much more to it than meets the eye.

First, regardless of how cute the shrew is, its name fits. The other meaning of its name, an epithet describing a scold, matches this little animal’s personality—antisocial, aggressive, territorial. “As two shrews meet,” writes Sara Churchfield in The Natural History of Shrews, “they freeze momentarily and then commence loud squeaking as they face each other. With their heads up, mouths open and snouts contracted, each one calls loudly to warn off the other.” A terrifying spectacle, for sure. The only time shrews interact willingly is to reproduce, and even that requires both the male and female to overcome their aversion for one another before copulation.

These animals are not repellent only to each other, but also to other animals, thanks to a stinky musk from glands on their stomachs and flanks—it’s why they’re often killed but not consumed. The northern short-tailed shrew is also uniquely armed with a more potent weapon: a venomous bite. Besides the echidna and the male duck-billed platypus, this shrew is the only other mammal to have poisonous saliva, chemically similar to that of a cobra—both a neurotoxin and a hemotoxin. A shrew bite can kill a mouse, and it can cause several days’ worth of pain in humans. Biologists say that the venom may allow shrews to cache some of their food, to keep captured insects alive and tucked in a burrow for a couple of days.

The shrew has to hoard food if it is to survive. As small as it is, its surface area-to-body mass ratio is the highest of all mammals; this means proportionately greater heat loss—and, therefore, a ridiculously speedy metabolism, with heart rates in excess of 900 beats a minute. Unable to hibernate, shrews pretty much live fast and die young, usually after less than one year, and usually due to food shortage.

Here’s another shrew superlative: Among mammals, it has the biggest brain in proportion to body size, accounting for about 10 percent of its weight. This ratio is even greater, interestingly, than that of humans. But size does not denote intelligence; the shrew’s comparatively big brain is focused almost constantly on finding food, because its metabolism dictates that it must consume its weight in food each day. (Like bats and whales, the nearly blind shrew uses echolocation in hunting.) And it has a catholic palate; with as many pests as are on its menu, it should be a welcome denizen in any garden. While its favorite meal is earthworms, it also likes anything with six or more legs, as well as slugs, snails, minnows, mice, amphibians, crayfish, other shrews, even its own feces. Not your tulip bulbs.

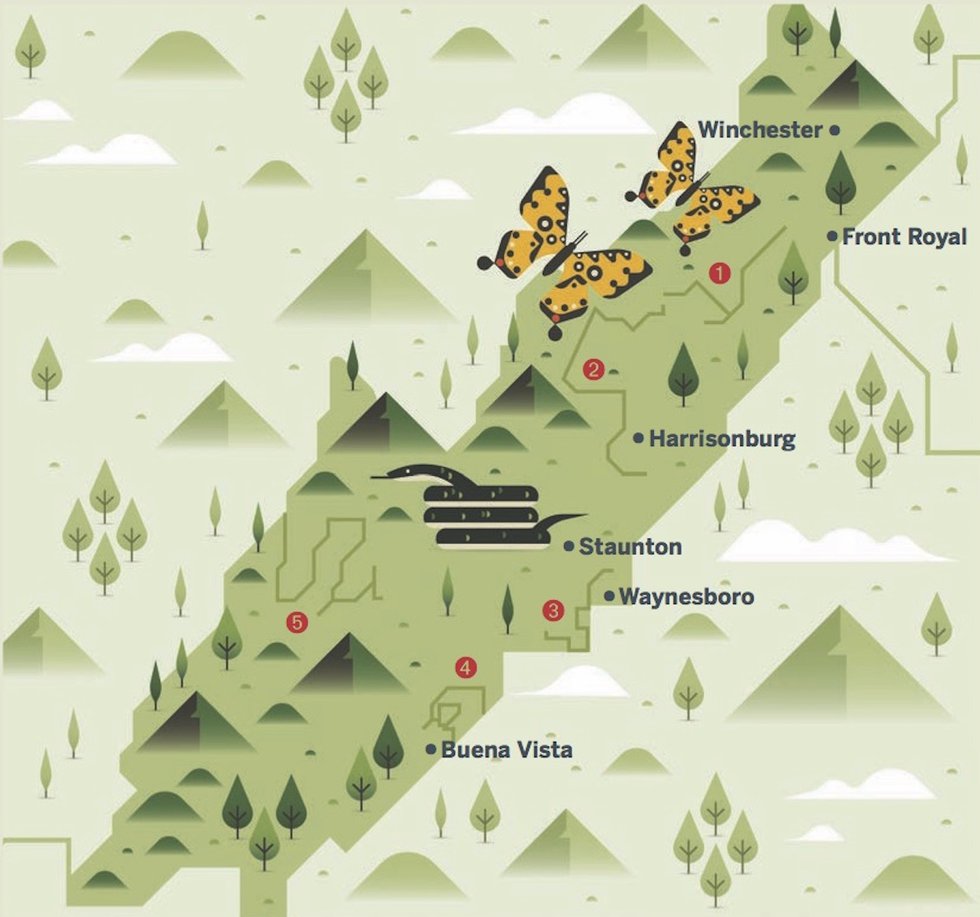

The animal’s only other real activity is reproduction. And it really doesn’t want to think about reproduction. Most shrew species mate in a cool 10 seconds, but the northern short-tailed shrew is the exception. Bob Pickett, a retired horticulturist and naturalist for the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club, describes its unique and much longer ordeal: After the five-minute act, the pair is stuck together for up to half-an-hour. It seems the male’s, er, member flattens and takes on an s-shaped curve, with “a set of hooked barbs that further secures his hold on her. … She then may drag him around backward for as long as 25 minutes.” It requires several such delightful encounters to induce ovulation. No wonder shrews are grumpy.

But they are cute. And now you know what your cat thinks of you.