In a wingsuit of fur, the Southern flying squirrel takes to the air.

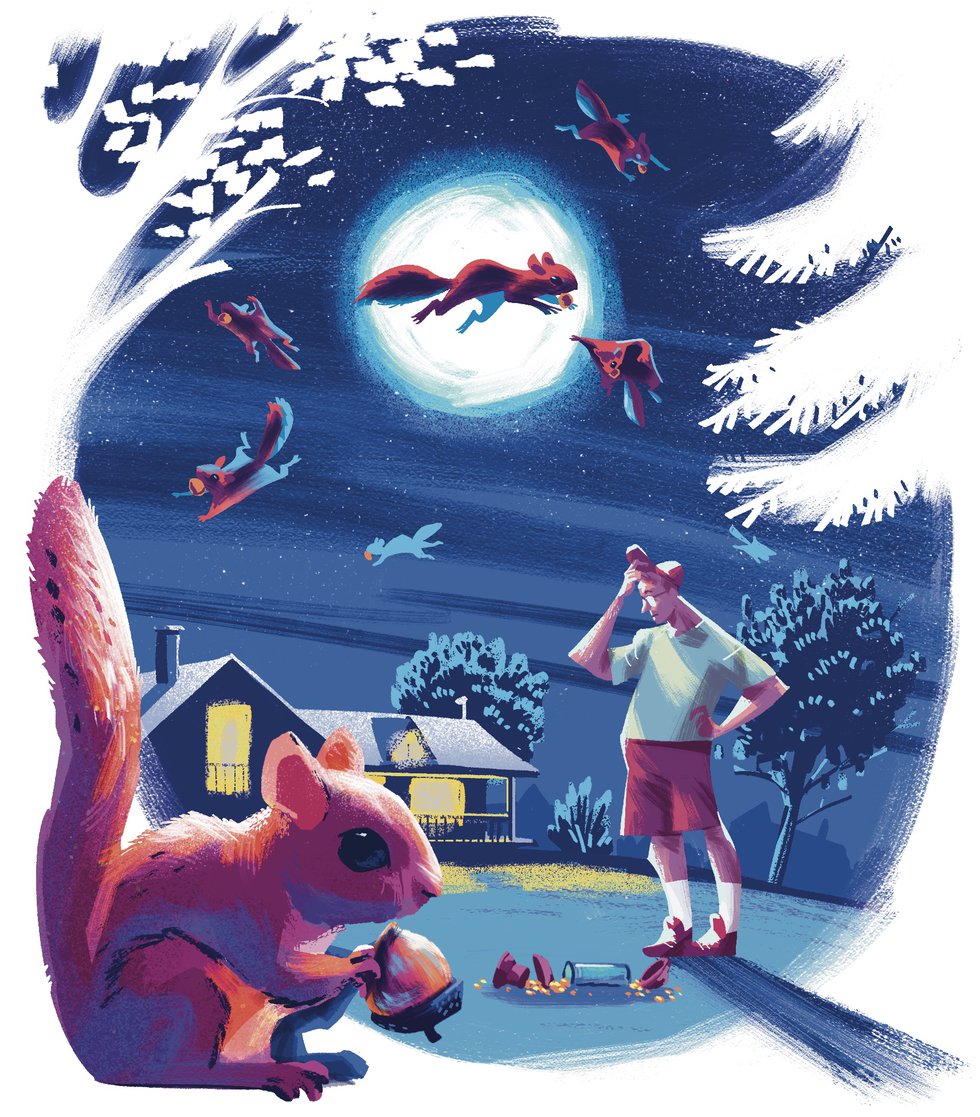

When evening falls, and we retreat to our lighted shelters, wild things stalk the night. Owls hunt on silent wings. Deer mow down the ornamentals. Coyotes trot heedlessly through backyards. And squirrels fly overhead? Why yes indeed, they do.

In the wee small hours, when the stars wheel above, the Southern flying squirrel takes to the air, a winged (sort of) denizen of the night, whizzing between trees with remarkable speed and agility. Yet despite the fact that this squirrel is relatively common in Virginia, its small size and post-sundown habits make it an unusual sighting. In fact, you might have a yard full of aerial squirrels and never even know it.

Todd Fredericksen is a professor of biology and environmental science at Ferrum College who has studied this elusive squirrel, and he can tell you from personal experience that They Are Out There. While researching them, he says, “I trapped 12 different squirrels on my porch one summer, coming into my bird feeders at night.”

It turned out that Fredericksen was the unwitting host of the perfect Southern flying squirrel habitat. Like the bane of backyard feeders, the gray squirrel, the Southern flyers remain active throughout the winter, Fredericksen explains. So they rely on larger nut-bearing trees like oaks and hickories that provide the food (what biologists call “mast”) they store to survive the barren months. But they also need a “relatively open area under the canopy,” Fredericksen says, that allows their preferred method of travel: taking flight (sort of) from tree to tree.

Southern flying squirrels don’t actually “fly.” Rather, these wide-eyed, chipmunk-sized creatures come equipped by nature with flaps of loose, furry skin called “patagia’’ that extend between their front and rear legs. The inspiration for the human wingsuit favored by extreme-sport BASE jumpers, this “extra blanket of fur,” Fredericksen explains, allows the squirrels to glide distances of 100 feet with ease. The longest scientifically measured flight for one of these squirrels was 200 feet. In flight, the squirrel’s tail, says Fredericksen, serves as a steering mechanism. “I have seen squirrels start gliding and then turn 90 degrees.”

Because owls are their major predator, and owls hunt by sound, these squirrels avoid the ground, with its noisy leaf litter. “We catch most of our squirrels up on the trees,” Fredericksen says.

By trapping the squirrels at night and releasing them by day, Fredericksen and his research team were able to follow their travels. The squirrels move from tree to tree, pulling up sharply to come in for a vertical landing on the trunk, then scramble up the tree to launch again from a height. “They try to go up to the very top of the tree so they can get better distance,” he says. “I had one that flew all the way across the yard, probably 150 feet.”

Fredericksen also found that despite their diminutive size, the squirrels are willing to put up a fight. “When you first catch them, they are very feisty and often difficult to handle,” he says. “They have so much fur that they can just turn around and bite you and get away.”

Yet it turns out that the way to a flying squirrel’s heart—or at least its acquiescence—is through its stomach. Fredericksen brought one of the captured squirrels to show his students, and it found a free lunch of peanuts and oats so entirely to its liking that “it sat on the table the whole time we had class, eating oats.” But don’t get any ideas of how cute it might be to keep one as a pet; that’s illegal in Virginia.

Fredericksen says the squirrels have a wide-ranging but somewhat patchy distribution in Virginia, likely driven by habitat and food. Nevertheless, given the trees that feed them, they adapt well to human-centric environments. Possibly too well. The squirrels typically nest in tree cavities, where in winter they will sometimes den up in groups to stay warm and conserve energy. But they may also discover that your attic makes for a cozy home too. “That’s when people discover they have flying squirrels,” says Fredericksen.

Otherwise, you might never know they’re there.

“That’s why I call them ‘seldom seen,’” says Fredericksen.

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue.