Keswick’s historic Castle Hill was once home to a famous penwoman who held everyone she met in her thrall. Today, that legacy has been revived for a new generation.

Stewart Humiston in the doorway to the formal living room.

A view of the estate’s extensive gardens.

The living room contains candelabras brought back from France by Judith Rives during the time that William Cabell Rives served as U.S. Minister to France.

The east-facing entrance to Castle Hill.

A portrait of Judith Page Walker Rives hangs in a hallway.

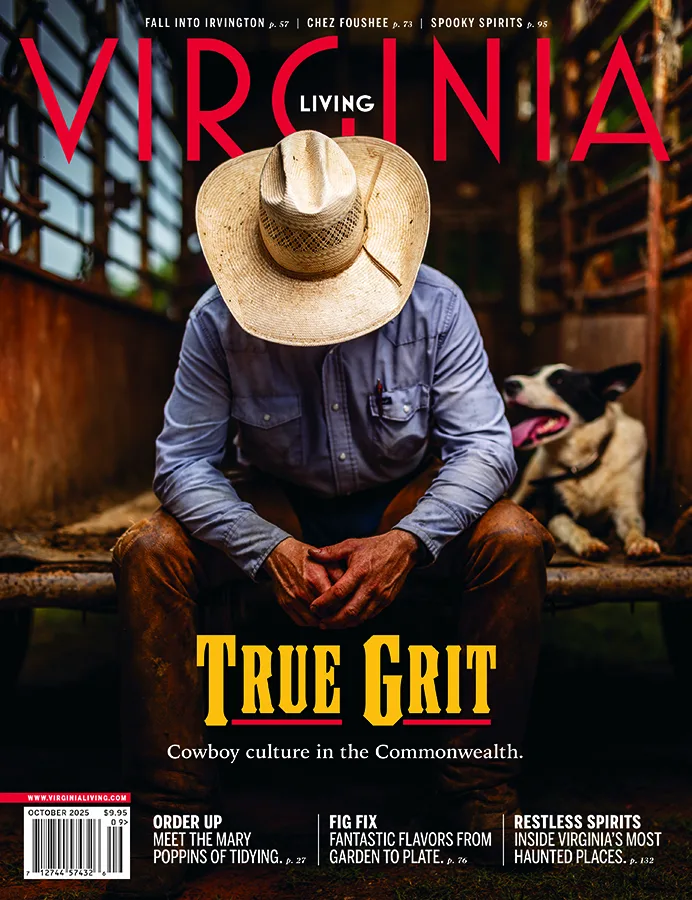

Humiston with Spacek and Hugh Wilson.

Sissy Spacek speaks to the group in the Summer Living Room.

The Summer Living Room joins the 18th and 19th-century parts of the house.

Charcoal self-portrait of Amélie Rives, 1892.

John Grisham and Chris Osteen on the last day of the retreat.

The library features a chair upholstered in fabric by Christopher Hyland.

Ray and Stewart Humiston and their dog, Chloe.

Castle Hill.

Guests enjoy an al fresco lunch at the poolhouse.

There is an old saying in the South,” says author and historian Barclay Rives: “Never let the truth ruin a good story.” But the story of Castle Hill, the grand old Keswick estate that belonged to Rives’ forbears for five generations, needs no embellishment. Here, one needn’t plumb for outsized tales of its explorers, statesmen, social elite and literati.

Though those tales include the derring-do of leaders from Colonial times through the Civil War, and count among the family’s closest connections founding fathers Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and James Madison, perhaps the most famous is of the beautiful Amélie Rives—one of the final generation of Riveses to live at Castle Hill. In 1888, then 26-year-old Amélie became the literary sensation of the day with the publication of her novel, The Quick or the Dead?, the story of a widow who falls passionately in love. The novel’s allusions to female sexual desire made Amélie a lightning rod for criticism and landed her in the national spotlight, by turns reviled and celebrated. But if there was one thing the public could agree on, it was that the siren and provocateur knew how to get people talking. And Castle Hill was her redoubt.

“There have always been people here at Castle Hill discussing ideas,” says Stewart Humiston, 58, who, with her husband Ray, purchased the estate in 2005. It is that legacy that Humiston is reviving with the recently-launched Readers and Writers Retreats at Castle Hill, the first of which she hosted in May along with partner Hugh Wilson, an Emmy Award-winning writer, director and producer who has lived in the area since 1992.

“I came up with the idea” for the retreat last June, says Humiston, an interior designer and former competitive equestrienne who first came to Keswick with her husband and three now-adult children in 2000. “I wanted it to be like an intellectual vacation, a holiday for the spirit.” The program? Three and one-half days of presentations by 10 authors, al fresco meals on the estate and at top Charlottesville restaurants, a wine tasting, a private tour of Monticello and an evening at the theater.

Barclay Rives, author of A History of Grace Church, Walker’s Parish and The 100 Year History of the Keswick Hunt Club, began the week by limning for the assembled dozen—writers some, readers all, from as far away as Texas—the history of the Rives family and Castle Hill, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The 600 acres that today comprise Castle Hill were originally part of an 18,000-acre land grant made in the late 1720s by King George II (via Virginia’s Royal Governor William Gooch) to Nicholas Meriwether II. A generation later, when Nicholas Meriwether III died, his widow, Mildred Thornton, married Dr. Thomas Walker. The couple had 12 children (all of whom survived to adulthood) and, in 1764, built a white clapboard house on the property facing Walnut Mountain to the west. Dr. Walker, who served in the Revolutionary War under Gen. George Washington, and in the French and Indian War, was a noted explorer who scouted the Kentucky wilderness, passing through and naming the Cumberland Gap. Physician to Peter Jefferson, he attended him at his death and became a legal guardian to the teenaged Thomas. (In 1781, Walker facilitated the escape of then-Governor Jefferson from capture by British troops when he and his wife waylaid Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, who was en route to Monticello where the governor and the legislature had fled from Richmond. The Walkers served Tarleton and his men a fulsome breakfast that gave Jack Jouett time to make his famous ride to warn the group to flee Charlottesville.)

The house wasn’t enlarged until 1824 when the Walkers’ granddaughter, Judith Page Walker, and her husband William Cabell Rives—who would serve in the Virginia House of Delegates, the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, and twice act as Minister to France—built the eastern-facing Federal-style Flemish-bond brick addition that today serves as the main entrance to the house.

Judith, an author in her own right, published several books in the 1850s, including a collection of European travel sketches and a novel, which was set in a thinly veiled Castle Hill. (“Truth is often more marvelous than fiction,” she wrote in Home and the World, which was published in 1857.) “Upper-crust women of that era did not ordinarily publish books—it was considered beyond the pale—so Judith did so anonymously,” writes Donna M. Lucey in her book, Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age, a historical biography of Amélie and her first husband, John Armstrong “Archie” Chanler (an heir to the Astor fortune). But how could Judith resist? The cast of characters at Castle Hill must have provided terrific fodder for her pen.

Judith’s husband, William Cabell Rives, too, was an author. Delegate to the 1861 Peace Conference in Washington, D.C., he spoke against secession but afterwards served in the Confederate Congress. He published the first biography of James Madison, a three-volume tome, and later edited a four-volume collection of Madison’s letters published by Congress in 1865, though he received no public credit for the work. (Barclay Rives, who is currently writing a biography of his ancestor and statesman, speculates that William Cabell Rives’ name was left off the latter publication because of his service to the Confederacy.)

The 1824 addition to Castle Hill, which looks out on a slipper-shaped garden designed by Judith, is ringed by giant boxwoods that conceal the house from view until coming upon one of the two narrow apertures that open onto the gravel driveway. Essentially two homes—one of the 18th century and one of the 19th, joined by a two-story hallway in between—Castle Hill comprises 19 rooms, six bathrooms and 8,500 square feet. The property includes 10 dependencies, a poolhouse (circa 1930s), two barns, a carriage barn and a garden cottage. (Modern additions include a pool, which was built in the 1970s and renovated last year.)

One of the Riveses’ five children, Col. Alfred Landon Rives, was next to inherit Castle Hill. An engineer trained in France at L’École des Ponts et Chausées, he helped to design the Cabin John Bridge in Washington, D.C., in the 1850s. He served as head of the Confederate Bureau of Engineering during the war, but afterwards—with the Southern economy in ruins and no jobs to be found—was forced to take distant posts, first in Mobile, Alabama, and ultimately in Panama. He spent lengthy periods of time away from Castle Hill, and his wife, Sadie Macmurdo, and their daughters Amélie (whose godfather was Robert E. Lee), Gertrude (who became an accomplished equestrienne and the country’s first female master of foxhounds), and Landon (a painter who was known to her family as Daisy and did not marry). Money was increasingly scarce during these years.

Though she traveled abroad frequently, Amélie would return to live at Castle Hill during both of her marriages: It was her touchstone. She divorced Chanler in 1895 after a tempestuous seven years together during which they often lived apart. (Lucey writes that it was suspected the marriage was never consummated) Just four months later, Amélie married a Russian prince, Pierre Troubetzkoy, a handsome, but aristocratically impoverished portrait painter, with whom she would remain until the end of their lives. (Oscar Wilde had introduced Amélie, who was also a gifted painter, to Troubetzkoy in London in the summer of 1894.) In a queer wrinkle to the story, the New York Brahmin, Archie, continued to support Amélie financially off and on for many years after their divorce, taking up residence at an estate near Castle Hill, which he later named The Merry Mills. (Archie was declared insane by his powerful family in 1897 and spent four years in Bloomingdale Asylum in New York. He escaped and returned to Virginia where he was much beloved in the neighborhood for his largesse. He would later establish the Keswick Hunt Club.)

“Fortunately forgotten” was all Amelie was quoted as saying near the end of her life of The Quick or the Dead? in a posthumous review of her work published in 1954 in The Georgia Review by her friend, author Virginia Moore. It is hard to imagine that Amélie, or anyone, could ever forget the furor that followed the novel’s publication.

“The lips, the kisses, the straining, clinging embraces; the wild, weird tear-fraught eyes; the romping and the rest of it,” wrote The New York Times, condemning the novel in its review of the book in November 1888. It would not, by modern standards, excite much more than romantic nostalgia but, at the time, the novel was excoriated by the clergy for its “‘pantherish’ carnality,” writes Lucey. Criticism came from within the Rives family as well, according to Barclay Rives, who says Amélie’s uncle, Francis Robert Rives, was “disgusted” with the book and wrote that “the men in his club found it ‘sale,’ the French word for dirty.” But she had piqued the public’s interest; the novel sold 300,000 copies. (Amélie would later ask her publisher to screen her mail to stanch the flow of vitriolic letters she was receiving.) She answered her critics by writing, in a preface to a 1906 edition of the novel, “It seems to me that books well meant, strongly written, and from a clean heart resemble mirrors, wherein every one who reads sees his own reflection. The pure will see purity—the foul-minded, foulness.”

But her work also earned admiration from leading literati, including Oscar Wilde, Henry James and Thomas Hardy. Later in her life, Louis Auchincloss, William Faulkner and others would spend time with the aging author (and morphine addict) at the decaying, but still gracious, Castle Hill, listening to her glittering stories. She did not publish another book for nearly 10 years after her marriage to Troubetzkoy, but by the end of her career she would publish more than two dozen works of fiction and poetry and five plays. Despite the controversy that always seemed to surround her, writes Lucey, by the 1940s, Amélie became “a respected member of the Southern literary establishment,” recognized as one of Virginia’s first women writers. Amélie lived at Castle Hill until her death in 1945, and the property was sold out of the family in 1947.

Clark and Eleanor Lawrence, the first non-Rives owners, “saved the place from becoming a ruinous heap,” says Barclay Rives. All of the owners since have taken beautiful care of the property, he says, “but the Humistons put a shine on it like no one else.” They placed the property in permanent conservation easement to prevent the threat of development, which loomed large in 2005 when they bought the estate. Says Stewart, “We do not just own Castle Hill; we are its custodians, and with that responsibility, we also feel a mandate to share its history and beauty with others. The retreat has provided the perfect opportunity to honor that.”

The idea was to try to get people close to the writer in conversation, explains Hugh Wilson, whose credits include WKRP in Cincinnati and The First Wives Club. He says that he and Humiston wanted to offer retreat-goers the chance to learn not just about what the authors are working on but also “how they write and what the work is like.”

Chris Tilghman, novelist and director of the creative writing program at UVA, spoke about the craft of fiction; Jan Karon, who wrote the bestselling Mitford series, discussed the emotional aspects of writing; and novelist Caroline Preston shared her process for collecting and organizing memorabilia for her book, The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt. Lucey, author of Archie and Amélie, historian Henry Wiencek, author of Master of the Mountain, a new and controversial book about Thomas Jefferson, and Tony Vanderwarker, author of the forthcoming Writing With A Bestseller, discussed their books.

Actress Sissy Spacek, who last year published a memoir, My Extraordinary Ordinary Life, added a bit of red carpet glamour to the final day of the retreat, describing for the group the process of working with her co-writer, Maryanne Vollers. She told them how she would scribble snatches of stories on bits of paper and later gather up the piles to review with Vollers. The experience of mining her memory and writing a memoir, Spacek told the group, which was charmed by her folksy candor, “made me realize the same things are important to me now,” as they were earlier in her life.

“I stay well organized, I know what happens chapter to chapter,” the retreat’s marquee author, John Grisham, told the group, getting right to the nuts and bolts of craft. Currently working on a sequel to A Time to Kill, published in 1992, Grisham says he writes two books a year, each plot carefully laid out before he begins writing. “You better know where you’re going when you start,” he says in the soft rounded notes of his native Mississippi. “Half of the first version of A Time to Kill was cut. I’m lazy. I don’t want to lose a year’s worth of work,” he says with a straight face, revealing a disarmingly wry sense of humor. Everyone laughs. This is what they came for.

“What kind of set the tone [for the retreat] is Stewart saying ‘I don’t see a bunch of people hearing a speech,’” explains Wilson. He says he and Stewart saw “people sitting in the living room and not so much just hearing a talk but talking, so that kind of made it that sort of intimate type thing. To my mind, all the ideas kind of sprung from that smallness.” He laughs, “Unfortunately, that’s what’s made it right expensive.” The price tag for the retreat: $3,500; lodging was arranged separately.

“I have to do more of this,” says Robin Williams of Goochland, author of two collections of essays, who came to the retreat to further her craft. “A writers conference is wonderful,” she says, “but this is so intimate, talking one on one with writers.”

“The only thing I can say is we’re tired,” says Wilson on the last day. Humiston is tired too, but energized as she talks about plans for the next retreats. Why is she doing this? Like Amélie, “I think people have stories they want to tell,” she says. “I just had to share this place.”

For information about retreats at Castle Hill, go to CastleHillRetreats.com