The brilliant artistry of Anne Blackwell Thompson.

You can still detect a little bit of Anne Blackwell Thompson’s Texas twang.

Raised in that curious suburban-ranching mix of what surrounds Houston, she studied studio art and art history at Texas A&M, in the Brazos Valley part of the state, as well as abroad, in London. When she gets excited, that twang tumbles out. But in reality, it’s more of a trawl, adding a bit of a southern drawl since she’s lived in Richmond for much of her adult life.

After college, Thompson found her way into creative careers, eventually settling in Richmond where she established herself as a much-sought-after historical decorative painter. “Bunny Mellon’s floors were my North Star,” she says, adding that her specialties were wood grains and unique techniques, like Venetian plaster, muslin, and strie.

Marriage and motherhood followed, as she built her reputation in this niche market, traveling the country for a host of clients—from Kennebunckport homes to historical hotels and resorts—for whom she painted the walls, ceilings, cabinetry, and floors using different painting methods she’d perfected.

A wall of unframed pieces in Thompson’s studio reveals the massive breadth of her work—and the beauty of life in color.

But the wheels fell off the wagon when Thompson was diagnosed in her early 40s with ovarian cancer. “I would describe it as a challenging medical maze that had lots of twists and turns,” she recalls. Many surgeries followed, which meant months and months of recuperation. She was often confined at home for months on end where she’d park herself on her bed, surrounded by books and magazines, with a lot of time to pass and a lot of thinking to do. “You can get caught spinning down those rabbit holes, wondering about my second chapter and what would bring me utter joy.” So it made sense that she chose to focus on what brought her pleasure and happiness. She was particularly taken with glossy mags on home décor. “They spotlight some of the most creative people,” she says. “And it was so inspiring at a time when I needed inspiration.”

Flipping through an old copy of House & Garden, she landed on an ad for a furniture line that featured Oscar de la Renta’s villa in the Dominican Republic. “I saw these incredible botanicals on the walls in the background. “They were mesmerizing .… these huge leaves that were floor to ceiling, and they turned out to be pressed foliage, not drawn or painted.” She was hooked.

On a Mission

Her new mission was to track down the artist, and since there was no credit in the magazine, it was no small feat. But eventually she struck gold. Stuart Thornton was the artist, a Brit who she learned was in the service to some of Europe’s oldest and wealthiest families. As it happened, his side hustle was pressed botanicals.

On a whim, which happened to be on one of the first days she’d been given the green light from her docs to leave her house and drive, she called Thornton, not knowing if the number was correct—it was from an old blog post—but he answered on the first ring. “I initially was interested in purchasing one of his masterpieces as a treat for the past year,” she says, “but we had such a delightful conversation that he suggested that I come over to study with him in Turin.”

She said “yes” on the spot, and within a few weeks she found herself meeting him in the lobby of her hotel in the ancient city, nearly paralyzed with emotions.

“I was thinking ‘what in the world am I doing?’ but at the same time I was over the moon to be in Italy.”

Lessons from Uncle Stuey

As the first (and only) graduate of the Stuart Thornton Botanical Apprenticeship Program, she says the experience was like no other. “Stuart was coming off of a breakup and wanted to go to the disco every night and dance his cares away to Lady Gaga,” recalls Thompson. “I felt like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz—I knew I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.” She describes a nonstop few weeks of harvesting botanicals in the Italian countryside, studio work, touring museums, and dancing in dark discos with Thornton’s newly replaced knees.

And in his studio, “he would tap my hands with a ruler,” Thompson says, describing Thornton’s teaching style. This she says with a half-horrified chuckle. “He was kinda harsh and didn’t mince words. I had to explain the term ‘gentle teaching’ and that teachers don’t hit students in America.” It was jarring at first, but the pair ended up laughing about it later.

Patience was not a concept with which Thorton was terribly familiar, but Thompson forged on, absorbing his lessons and following her own instincts, putting her own spin on how to harvest and preserve plants. Years later, she even taught Thornton a few of her own lessons, including a tutorial on seaweed harvesting when he visited her in Richmond.

She returned home from her adventures with Uncle Stuey ready to turn the page—on her diagnosis and her career.

A New Day

Today, Thompson’s Scott’s Addition studio—Blackwell Botanicals—is like a natural history wonderland, full of her art in different stages. It’s both a working studio and a gallery, with framed pieces hanging on walls and leaning together in groups and those in presses. Shelves are full of works bound for the framer.

Penelope, her taxidermied porcupine, is the official greeter (they’re bigger than you think). Ziggy, a zebra mount, gazes down from on high, beneath whom Albert the alligator—named for an orphaned family pet—shows off a fierce set of choppers. “We had him for about a year while we were living in Louisiana,” Thompson explains, “but he was eventually released back to the swamps to mingle with his own kind when he got a little too toothy.” And there’s a butterfly collection, too. Time after time, she greets visitors and customers with a broad smile, a twinkle in her eye, and a big, Texas-sized “welcome!”

Thompson harvests flowers at Historic Tuckahoe to add to her signature wheeled basket.

At any given moment, Blackwell will dash off to a show—from Trade Secrets in tony Sharon, Connecticut, unofficially hosted by style maven Bunny Williams, to Antiques at the Gardens in Birmingham, Alabama, to the Kips Bay Decorator Show House Palm Beach. Depending on the season, she might be found harvesting seaweed along the South Carolina coast with her self-described wagon-puller Jane Butler. She’s harvested native plants for the Four Seasons Resort in Lanai, Hawaii, tobacco from a North Carolina farm, and peanuts from a family farm near Smithfield. “Custom commissions are some of my favorites,” says Thompson, recalling a special project she did for interior designer Janie Molster where she harvested from a client’s garden in Captiva. “The hurricane took out everything months later but the client had a special collection to remember their previous garden.”

From weeping wisteria to elegant orchids, voluptuous peonies, and native grasses, nothing is off-limits to Blackwell’s keen eye for potentially pressable botanicals, with her plant radar constantly in overdrive. Her vehicles vary in size and are scrupulously organized, with shelves and crates and boxes labeled and stacked. Some of her presses are the size of ping-pong tables, and if she’s harvesting large specimens, they get packed too. She’s never without her stash of supplies: scalpels, tweezers, X-Acto knives, clippers, axes, machetes, scissors, ladders, and her trusted Wellies—aka snake boots. “I’ve blown through five pairs in as many years,” she says with her signature Texas trawl. “These things get a lot of mileage.”

From weeping wisteria to elegant orchids, voluptuous peonies, and native grasses, nothing is off limits to Blackwell’s keen eye for potentially pressable botanicals.

Impressive Accolades

“She’s so unassuming,” says her sister, Kathryn West, “but she’s incredibly talented. It takes a real gift to master such an incredibly esoteric artform.” And her considerable talent has been recognized with accolades spanning far and wide. She’s been the artist-in-residence at Historic Tuckahoe in Goochland County, as well as at Ladew Topiary Gardens in Maryland and Brookgreen Gardens at Murrells Inlet in South Carolina. And last year, she was invited to participate in the Art in Embassies program, U.S. Department of State in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The U.S. Ambassador to Slovenia, Jamie Harpootlian, is a native South Carolinian (and Mary Baldwin University alum), who selected her work because she wanted flora represented from her home state. “I adore her,” she says of Harpootlian, adding “She’s a total rock star and a wonderful ambassador to shine a light on art and artists from South Carolina.”

Thompson counts among her mentors and fans some of the horticulture world’s superstars and leaders at top public gardens. She also makes regular pilgrimages to botanical gardens. At Longwood Gardens, she’ll check in with her friend Tim Jennings, who tends their magnificent water lily collection and is considered one of the world’s foremost authorities on their culture. (Some water lilies under Jennings’ care are big enough to seat two for dinner.) Thompson was invited last year to exhibit her work at Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden in Richmond. “Anne’s work is beautiful, delicate, and intrinsic,” says Director of Exhibitions Michelle Israel. “Her artistic composition and detailed technique make each piece dreamy; they can transport you to a field of scented flowers, a lush tropical paradise, or make you feel like you got lost in the woods. Her style is both traditional and modern but always elegant, preserving the ephemeral in an ethereal way.”

A wall in Thompson’s studio temporarily dedicated to Nymphaeaceae (water lilies). Thompson’s studio is constantly in flux with the seasons, and she always encourages clients to visit and experience her work in person.

A Meticulous Process

Each bloom and leaf requires a different technique to preserve. Thompson deconstructs, dries, reconstructs, mounts, and presses each specimen, employing the skill (and tools) of a neurosurgeon. Some pieces take up to nine months to complete. Elephant ears, for example, require months of being in a press in order for them to adequately dry. “Lily pads and seaweed are like tending a newborn,” she says, “changing out blotting paper every four to six hours at the beginning.” Dutifully, Blackwell sets her alarm and babysits her charges, carefully tending to them 24/7 at the required intervals.

Nigella, on the other hand, might not require as much time to dry, because they don’t live their lives in water, but their fine, feathery foliage must be meticulously positioned in the press so that their delicate, wispy leaves aren’t compromised in the pressing process and the blossom shows. For this, Blackwell uses tweezers and a scalpel to make sure the specimen is mounted on the paper just so.

Roots of Inspiration

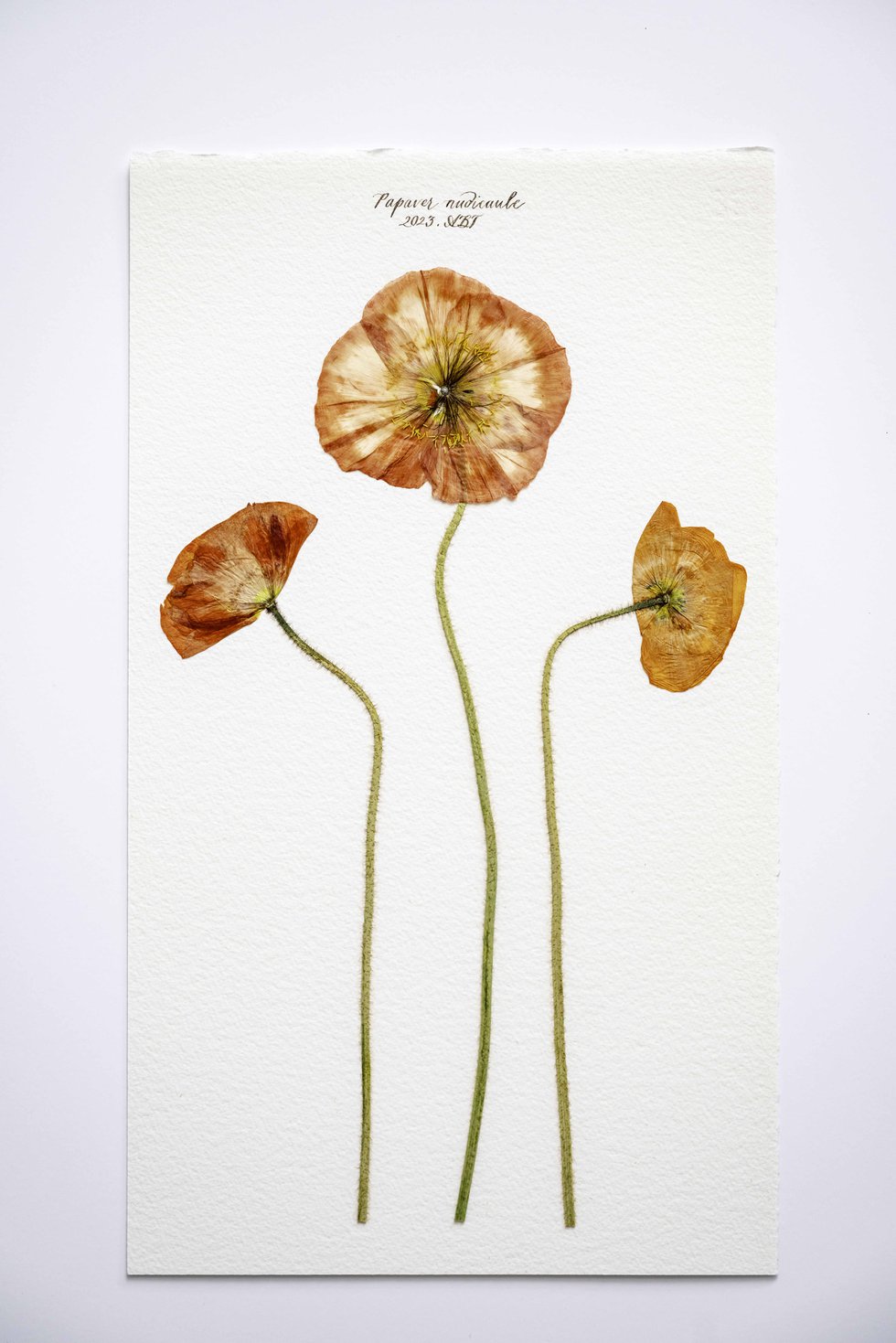

These vibrant Papaver nudicaule (Iceland poppies) are native to subpolar regions of Asia and North America.

To pinpoint Thompson’s inspiration is a loaded question. She draws from her childhood in both Texas and Louisiana, and her 20s, during which she ricocheted around the world, spending time in the South Pacific, Asia, England, Mexico, Eastern Europe, Iceland, Nepal, New Zealand, to name a few. From place to place, the vast world of botany unfolded in front of her and ignited a fierce curiosity about the plant world.

She also admits to having a serious lady-bot crush on Scottish-born botanist, Elizabeth Blackwell, the 18th-century botanical illustrator and plant taxonomist. That they share the same name is a crazy and curious coincidence. Thompson had the opportunity to study an original of Elizabeth Blackwell’s pioneering masterpiece, A Curious Herbal, published in 1737 and included in Bunny Mellon’s collection at her Oak Spring Library in Upperville. And in her signature trawl, Thompson says, “I’d like to think that maybe in another life I was Elizabeth Blackwell’s neighbor. Or maybe she’s my great-great aunt, and I inherited her passion and interest in botanicals.”

But maybe what also propels her is a touch of survivor’s guilt that accompanies anyone who watches their fellow comrades succumb to the disease she has beaten. What momentarily derailed her gave her a genuine appreciation for, quite simply, the gift of life—its beauty and its transience.

Now, surrounded by the bounty of botany, in her studio and as she happily forges through the marshes and mountains where she harvests and admires the daffodils and peonies that bloom in her garden, she knows, just like life, it’s all temporary. But her job is to capture a moment in time—when a peony is at its pinkest, a hydrangea is at its fluffiest, or a mimosa tree is about to burst with its powderpuff blossoms. With Blackwell Botanicals and all her traipsing and harvesting and pressing, she captures the ephemeral nature of life, cultivating gratitude, empathy, and resilience, one plant at a time.

This article originally appeared in the June 2024 issue.