From oyster shuckers and banjo players to gospel singers and decoy carvers, Virginia’s state folklorist Jon Lohman champions the artists and the traditions that are the soul of our cultural heritage.

To watch performances and listen to recordings from Virginia Folklife artists, plus find a list of 2016-2017 Master Folk Artists and their apprentices, click here.

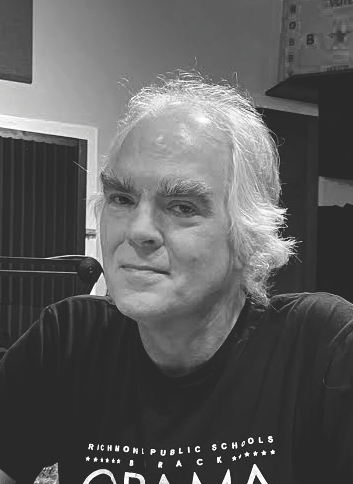

It’s the last day of the Richmond Folk Festival, and Jon Lohman, Virginia’s state folklorist, looks plum tuckered out as he stands on the Virginia Folklife Stage—one of the special attractions at the three-day music and folk arts gathering that takes over the riverfront in mid-October.

Lohman is about to introduce the delicate Sephardic balladry of Flory Jagoda, 87, a Jewish exile from Bosnia who lives in Northern Virginia. Responsible for programming two days of music on this stage from artists across the Commonwealth, and for curating and displaying at the festival a collection of indigenous crafts, food and folk art, including a functioning whisky still, Lohman’s heavy-lidded eyes are watery by this point, his shirt partially untucked as he stifles a yawn. It’s the home stretch of a haul that has taken three months of planning, logistics and navigating nit-picky details.

“You guys have been really attentive. This is the MENSA of audiences,” he says jokingly to the crowd. But before he can continue there is a commotion behind him—a couple of chattering voices, one of them belonging to a venerable and highly-decorated old-school folklorist. Lohman turns around and tells them to quiet down. Reacting like naughty schoolboys, they stop and apologize. The veteran folklorist, who has shushed a few in his time, chuckles.

It’s a rare sight to see the affable Lohman, a boyish 47, lose his cool. But no one, not even a senior figurehead who practically invented his vocation, is going to disrupt this special weekend program—a tribute to Virginia’s 11 musical winners of the NEA’s National Heritage Award, the highest honor given to traditional folk artists in the country. Thanks to Lohman, the stage is hosting appearances by NHA winners, including musicians Jagoda, Ralph Stanley and Jesse McReynolds, and Crooked Road music trail originator Joe Wilson—the pillars of classic Virginia folk music.

But it’s only part of Lohman’s job to showcase homegrown culture for gatherings like this. He’s also out to make sure Virginia’s traditions survive and to expand the definition of what “traditional arts” can mean.

“They say that America is a melting pot,” he says. “People come here and they add their part and blend in. But this isn’t a very good metaphor. Actually, when people come here and settle, their traditions become even more important to them …. they work hard to preserve them. Everything came from somewhere. It comes here, it changes, it comes in contact with other cultural traditions, and there’s this wonderful collision that produces new things. And that becomes part of Virginia.”

When Lohman arrived in 2001 at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities (VFH), the Charlottesville-based nonprofit cultural organization that oversees the Virginia Folklife Program, he wrote a grant application to the National Endowment For the Arts to help start an apprenticeship project that would pair disappearing Virginia master craftsmen, musicians and folk artists with younger practitioners. He’s done it every year since, he says, “with an eye toward not just documenting things but to helping communities that are trying to keep things going in this modernized world. When these people go, they are going to take all of the knowledge with them.”

In Lohman’s 2007 book, In Good Keeping, which documented the first five years of the project, the late banjo master and folk music legend Mike Seeger (an early program participant) wrote, “It is a valuable and continuing heritage that is being threatened by the mass media. We have to go to extra lengths to give it a boost, which is one reason that things like the apprenticeship program are so important.”

The initiative celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2012 and has been, by any measure, an inspiring success. And not just in music. The list of cultural specialties the program has preserved is staggering in its scope, encompassing everything from West African and Chickahominy Indian traditions to decoy carving, boat building, canning, basket making and automobile pinstriping—even Brunswick stew cooking and oyster shucking.

“Jon is really a wonderful asset to the state of Virginia,” says Grayson County’s Emily Spencer, a claw hammer-style banjo master who participated in the program in 2010. “One of the things I like about him as a folklorist, which you don’t always see, is how open-minded he is to different types of folklife throughout the state, from Arlington to the Eastern Shore to Southwest Virginia. It’s amazing to think about all of the different things he’s brought to that program.”

It’s not too complicated, Spencer says of the program. The apprenticeship pairs—typically, eight a year—receive a small stipend and are told to get to work. “What you do is spend extra time teaching and learning, sometimes formally and sometimes informally, over the course of nine months to a year,” explains Spencer, adding that the program “also helps to bring families closer together.” She would know, having apprenticed son Kilby and daughter-in-law Amanda; her husband Thornton earlier apprenticed daughter Martha in old-time fiddle playing. (They all perform together in the Whitetop Mountain String Band.) The Spencers aren’t the only examples. Many apprenticeship pairings see traditions passed down to sons, daughters, nephews and grandchildren. “We don’t pick the apprentices,” Lohman says. “We leave that up to the master artists.”

Lohman was first introduced to folklore at the University of Chicago in 1996. “I didn’t know it existed,” Lohman tells me, refreshed, a few weeks after the festival is over. “I didn’t know what kind of field I wanted to go into. So I took a course by the anthropologist James Fernandez, and I was really turned on by the material.”

What attracted him wasn’t the academic and theoretical side of it but the sense that one can help to keep a community’s distinctive traditions alive in the present day. While many scholars look down at their cultural subjects from a lofty “theoretical perch,” Lohman explains, folklorists tend to work from the ground up. “Fernandez told me something that I’ve never forgotten. He said, ‘In folklife, the bricks can touch the ground.’”

Lohman has his Aunt Henny to thank for all of this.

“She was way into Pete Seeger, the Weavers and all of that kind of stuff …. a real folkie,” Lohman recalls. His aunt would take him to the Clearwater Folk Festival, an annual event held not far from his boyhood home in Irvington, New York. “I saw all kinds of music, was exposed to so many things there at an early age.” For years, he thought that Irvington, a suburban enclave situated along the Hudson River in Westchester County, was culturally bereft. “But everywhere’s got an interesting culture,” he says, “if you look for it.”

One of his earliest musical awakenings came when he heard the gospel-tinged theme from “The Jeffersons” TV show. “I was like, ‘What the hell is that?’” But Lohman clearly recalls when he first heard the real thing—gospel legend Shirley Caesar singing on the radio. “My mother was listening to her. I was blown away.” It’s perhaps no coincidence that much of his folkloric focus has been to help preserve Virginia’s gospel traditions, in all styles. He has helped to produce recordings by several indigenous religious performers, such as the evangelist Frank Newsome and Richmond’s Maggie Ingram and the Ingramettes.

“Jon Lohman is just like my natural brother,” the Rev. Newsome says from his home in Haysi. Like many apprenticeship masters, Newsome—one of the few surviving singers in the Old Regular Baptist line-singing tradition—was awarded an NEA National Heritage Award in 2011 thanks to Lohman’s patronage. “Jon Lohman and [country music singer] Jim Lauderdale produced my CD and all proceeds went to my church. Thanks to that, we put a new roof on and got air conditioning put in,” says Newsome.

The Rev. Terrence Paschall Sr., the leader of the Paschall Brothers, a group from Chesapeake furthering the tradition of Tidewater a cappella gospel singing, says he thanks God every day for leading Lohman to his doorstep. “He’s initiated a lot of things for us,” says Paschall, echoing Frank Newsome. “He’s become like a brother to us.”

The Paschalls were among the first to enter the apprenticeship program, and Lohman successfully nominated them for a 2012 National Heritage Award. He has also produced several CDs by the group, including “Songs For Our Father,” a disc released on a VFH-affiliated label. The Rev. Paschall presided over Lohman’s 2009 wedding to Tori Talbot, the VFH’s events manager.

Lohman, who comes from a Jewish background, envies those with strong faith, like Newsome and Paschall, but he calls himself “spiritual” rather than religious. “A lot of these folks I work with have difficult lives, many living with poverty, and they still have that kind of faith and gratitude. I mean there are a lot of things I take for granted in my life, but to be able to say, ‘He woke me up this morning’ and to be thankful for that …. ” he says, his voice trailing off.

After he left Irvington, Lohman attended Boston University—an early goal was to be a newscaster—but he transferred because, he says, “I didn’t feel the community there.” He then spent a year at the University of Vermont and, after that, attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: “It was my first time living in the South and I just took to it. It just felt right.” He then hooked up with Teach For America, a national teacher corps that places recent college grads in under-resourced schools. “I got put in an elementary school in New Orleans …. here I was, 22 years old, from this little town in Westchester, thrust in this school where I was the youngest teacher there, one of only two males in the whole staff and the only white person in the entire building.” It was a trial by fire. “They gave me two reams of carbon paper and a box of chalk and said, ‘These are your supplies.’”

He remembers an experience on the school playground. “Some older boys were shooting baskets and listening to rap music. And in the background, the rappers were sampling a Meters tune. I just sort of mentioned to the kids, ‘Hey, that’s the Meters.’ And they had no idea of what I was talking about. They didn’t have a clue. And I was like, ‘The Meters, you know, they live in this town …. pioneers of funk music.” Their blank looks startled him.

“These kids grew up in this incredible, culturally rich place, and they didn’t know about it. And I remember hanging out in the teacher’s lounge and a guy who worked there, his name was Sam Henry, he was a local keyboard player as well, and I mentioned this to him. And he said, ‘Hey, you should give George a call, George Porter, the bass player for the Meters.’”

Porter’s classroom visit was “a transformative day,” says Lohman. “For a lot of the kids, it opened up eyes.” But the teacher was transformed, too. He ended up writing a grant to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation so that he could bring more local musicians into the public schools. “So that’s what I did—folk arts in education. That’s where the bricks touching the ground first came in.”

But not everyone shared his vision. “I remember approaching the Louisiana state arts council, and they told me that these people I was bringing in, like the Rebirth Brass Band, were not traditional artists. They defined that as Cajun and more rural artists. It’s part of that same notion that folk arts, traditional arts, are only really found in a rural setting. It’s misguided.”

Recognizing that he needed credentials to go forward, he eventually earned a doctorate in folklore at the University of Pennsylvania. But teaching wasn’t his goal. “The whole academic thing, writing for journals and stuff, didn’t appeal to me. I wanted to be … more in the public.”

“He loves to travel, that’s the best thing for him,” says Talbot, his wife. “In a way, it’s sort of dreadful for him to be at home on a weekend dealing with the chores of everyday life, mowing the lawn or raking the leaves because there’s probably something going on out there that he’s not participating in. He’s got a restless spirit.”

Jonny and the Jambusters.

Jon Lohman and Buddy Pendleton.

Jon and Dylan Locke at the Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Gallery at the Floyd Country Store.

Charlie McClendon.

Photos by Pat Jarrett/Virginia Folklife Program

Since he took the position of state folklorist in 2001, Lohman has logged many miles traveling the state. And he has often had to argue that certain uncovered traditions are folklife-worthy (hot rod building was a particularly hard sell). At times, it is the artists and craftspeople who need convincing. Some, like a group of Mennonite carriage makers from the Shenandoah Valley, have repeatedly refused advances.

And then there’s Wayne Henderson, the famed guitar picker and instrument maker from Rugby. “I have been trying to get Wayne into the program for years,” Lohman says with a laugh.

In 2013, it finally happened.

That year, Wayne Henderson sits on the stage of Charlottesville’s Southern Music Hall alongside his longtime accompanist, Helen White. It’s the first in a series of intimate club concerts that the VFH is presenting at the Southern, and Henderson is sharing the bill with another apprenticeship master, Fredericksburg blues singer Gaye Adegbalola.

Famous for his meticulous, hand-crafted guitars (Eric Clapton once waited nine years to get one, as recounted in the book, Clapton’s Guitar), Henderson tells the crowd that “the most exciting thing for me right now,” is going through the VFH apprenticeship program with his 27-year-old daughter, Jayne.

“She asked me if I would help her pay off her student loan, and I told her, ‘Well, you need to do that yourself,’” he recalls to the audience. “I said, ‘Let me show you what to do.’ So I gave her my best wood and made her do every lick of the work. And she got, like, $25,000 for it to help pay off her loan. .… She’s been making guitars ever since, and she’s being properly trained now through the apprenticeship program.”

Henderson strums his guitar a bit and tells the crowd about the fiddle that White is using. “It’s only one of four fiddles I’ve made, and I’m teaching my daughter how to do that. Just get some nice curly maplewood and spruce on the top and a couple of pieces of ivory, and I show her how to use that whittling knife and cut off everything that don’t look like a fiddle.”

After the show, Henderson talks about Lohman’s work as state folklorist. “You see him into a little bit of everything, and he’s really into our kind of music and our culture where we live and all over Virginia. And he’s a pretty good musician himself. He blows the harp pretty good. He gets into our jam sessions .… one of the few folklorists who do that, really.”

I ask about Lohman’s constant requests over the years for Henderson to share his expertise, to pass along his unique talents, through apprenticeship. “Well, when I thought about my daughter doing it, that was really appealing then. I mean, she’s used to my little old shop, used to the dust, used to the small space. And she’s really taken to it …. she has 26 orders for instruments now.”

Henderson smiles broadly, a proud artisan and an even prouder father. And through the din of the departing crowd and the background music of a fiddle record being played, you can hear another brick touching the ground. VirginiaFolklife.org

Don Harrison wrote the liner notes for the Maggie Ingram and the Ingramettes CD produced by Lohman for the VFH and has worked on other VFH-funded projects.