The candy darter is one of Virginia’s seldom-seen gems.

One of the gifts Virginia offers is the sheer variety of our native species. We’ve got eagles and oysters, sharks and bears, venerable trees and vanishingly brief spring ephemerals, crabs and copperheads, mighty elk and mini weasels—a veritable bounty of flying, leaping, splashing, scuttling, leafing, slithering, soaring, blooming plenty.

Some are familiar sights, from the nuthatch at your feeder to the oaks towering overhead to the deer nibbling at your greenery and the poison ivy tickling at your ankles. But others that call Virginia home live their whole lives in places most of us will never go and settings few of us ever see. One of these is the colorful candy darter.

A mere four inches long at full size, the candy darter is small. It’s also rare. There are some 248 species of darters in the world, all of them found only in North America, and all but one of these found east of the Continental Divide. Of those 247 species, most are found in the southeast. And within the southeast, candy darters are known to be present only in two states—West Virginia and Virginia. What’s more (or less), here in the Commonwealth, they have been found only in parts of a mere four mountain streams. This is not a fish you’re going to stumble across in any casual outing.

But Mike Pinder, who is a nongame and endangered fish biologist with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, has the rare privilege of being able to say he has indeed met the candy darter. And you can call him a lucky nongame and endangered fish biologist for having had that opportunity, because the candy darter—specifically the male of the species—is something to see.

Arrayed in brilliant crimson, aquamarine and gold, it looks like a fireworks display with fins, rivaling any tropical fish in beauty, says Pinder. It is such an extravagantly colorful fish that it’s almost as if nature was trying to use up a bunch of its most precious leftover paints one day and threw the whole lot at the candy darter. (For images that—almost, says Pinder—do the fish justice, search for the candy darter in the “Photo Ark” section of National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore’s website, JoelSartore.com.)

The candy darter’s habitat is narrow and specific—the shallow, fast-running riffles and runs of the streams where they live, and where the candy darter is perfectly adapted to be right at home. “They are long and slender, so when they face up the river they don’t have much drag,” explains Pinder. “And their pectoral fins are shaped such that the water just pushes down on the fins and holds them on the bottom.” The name “darter” comes from the way the fish move about in this swiftly flowing environment, he says. “Typically they just kind of scoot on their bellies—dart here and dart there.”

Because this is territory where larger, predator fish not similarly adapted can visit but can’t stay for long, male candy darters can risk being so colorful. And why they are so colorful, says Pinder, is for the same reason peacocks flaunt their tails, fiddler crabs wave their claws, and the Golden Bachelor got a spray tan—they’re looking good for the ladies.

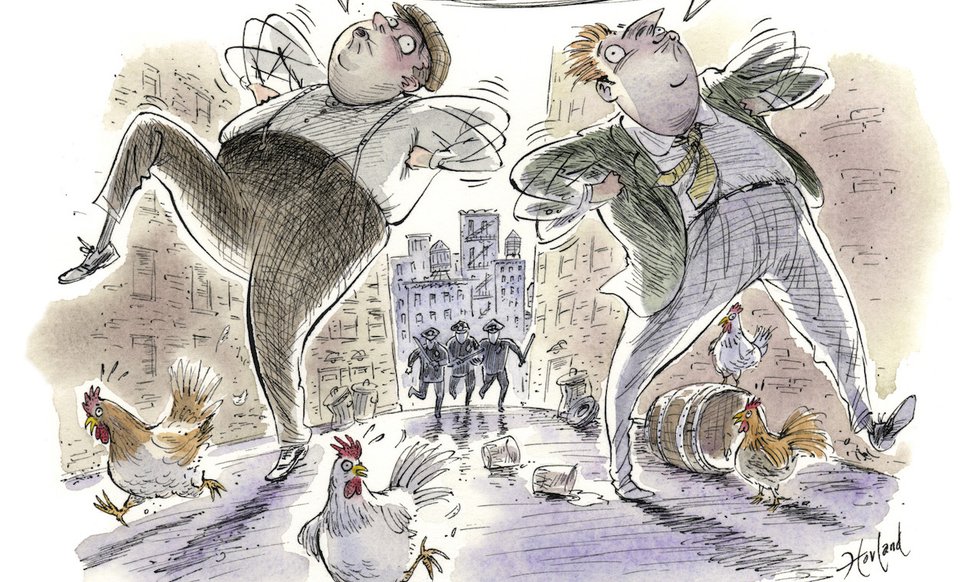

Alas, though, beauty alone doesn’t win hearts. So throughout the breeding season, says Pinder, males vie for females’ attention by sparring with each other. And that takes a toll. If at the start of that season they’re swanning about in their finest, by the end, says Pinder, “The males are just a wreck. Their fins will be all chewed up, and they are not that pretty, because they have been through the ringer, one fight after another trying to compete with the other males.”

All this flourish and fury carries on, year after year, with most of us never the wiser. Yet just because species like the candy darter might be little-known and rarely seen, that makes them no less valuable in the rich tapestry of our state’s native flora and fauna. As a conservationist, says Pinder, “I don’t want to leave a world for future generations that is full of just cockroaches and starlings. I want a really rich world with a good diversity of species, knowing that there is beauty out there in the wild. And future generations can look back and say thankfully that the people who preceded them were thoughtful enough and caring enough to make sure these species are still around.”