Ocean View Amusement Park was a major seaside attraction for 80 years, offering fishing, rides and crazy sideshow acts.

Sand and Spectacle

A bird’s-eye view of downtown Ocean View, 1951

Explosion brings down The Rocket

Sunbathers, July 4th, 1931

After a successful debut at the Jamestown Exhbition in 1907, Abe Doumar moved his ice cream cone concession to Ocean View Amusement Park later that year. After a hurricane destroyed the park in 1933, the Norfolk landmark moved to its final location on Monticello Avenue.

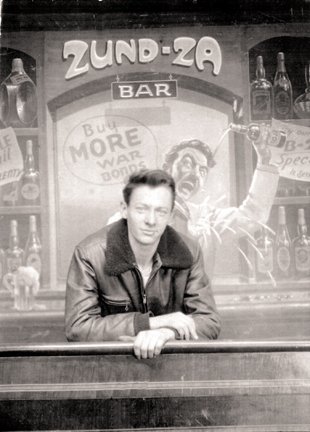

Dudley Cooper

In the 1930s, fun seekers could rent a rowboat for 50 cents an hour for a leisurely outing on the Chesapeake Bay. A dollar more got you an awning to shield yourself against the sun, as well as an attendant to row the boat for you.

A park sign in 1977 (courtesy of Thomas Cherry)

Pinewell resident Kathy Wiley at the Ocean View Park Fishing Pier, 1961

Little Taco jumps during a performance

A couple poses in August 1915

A couple poses for a photo souvenir in a boat scene

Virginia C. Dowe of Norfolk was selected as Miss Ocean View 1928 during the annual Mardi Gras festival held at the park.

The Roll O Plane, also known as the Salt & Pepper Shakers, in 1958

Have Fun but Behave Yourself, 1931: Night watchman C.W. Spangler (standing) and two unidentified members of the Ocean View Amusement Park police force pause for a photo in front of Doumar’s ice cream concession. Photo courtesy of John Campbell.

Ocean View artist Paul “Red Rooster” Trice at the park photo studio around 1945. Red earned his nickname because of his fearlessness as a wrestler at Granby High School.

Roland Sadler with daughter Margaret at Ocean View Park, c. 1920s

Roland and Edith Sadler, c. 1920s

Lucia Belle Sterling, Betty Evans, Debra Saunders

The Skyrocket rollercoaster, July 4th, 1969

Postcard of the Pavillion

In 1979, a massive explosion left Ocean View Amusement Park’s signature wooden roller coaster, The Rocket, a smoldering heap of splintered timbers and twisted metal. No, it wasn’t a terrorist attack, but rather the deliberate destruction of the park’s most popular attraction. The coaster’s demolition had been scripted—literally. Playboy Productions, an offshoot of the men’s magazine, had heard that Ocean View Amusement Park was closing and offered to blow it and other park facilities up in exchange for the right to feature the blasts in its made-for-TV suspense thriller, The Death of Ocean View Park.

The Rocket’s destruction was symbolic: It capped the closing of Ocean View Amusement Park after a roughly 80-year stretch of entertaining people in the Tidewater area. When the coaster collapsed, a crowd of nearly 1,000 wistful onlookers let out a collective groan, according to newspaper reports. And understandably so: “It was a sad day,” remembers longtime Ocean View resident Tom Cherry, 65, who witnessed the destruction. “People were really upset. They knew it was going to happen, but they were shocked. I used to go down there to ride the roller coaster the first day it opened up every year. Watching it go felt like a big loss.”

Indeed, Ocean View Amusement Park had been a major beachside attraction for decades. It was one of the last of the old-fashioned parks—since replaced by the high-tech scream factories prevalent today—and its demise signaled the end of a simpler era when an exhausting day’s worth of wholesome entertainment could be had for a few dollars.

Gone were the carnival games cluttered with trinkets, and the sweet scents of concessionaires’ edibles mixing with the salty breeze blowing off the Chesapeake Bay. Gone, too, were the weekly fireworks shows, the flashy penny arcade and the petting zoo. Gone were the wonderfully zany sideshows—the two-headed cow, for example, and “Captain Suicide Simon,” who squeezed into a coffin-sized wooden box, lit sticks of dynamite and survived the blast. Gone were all the rides—the Ferris wheel, the carousel and, most visibly, The Rocket—that had delighted thrill seekers for decades. Their wooden frames, their old bones, paid sad homage to the park’s postwar heyday, in the 1950s and 1960s, when Ocean View Park attracted more than a million visitors a year. “Parents would pull up and kids would pile out of the car,” recalls Joe Leatherman, a board member of Ocean View Station Museum, a small local museum named after the streetcar station that served the area in the early 20th century. Leatherman says he spent a substantial part of his childhood at the park. “This was back before the time when you had to worry about somebody abducting your kids. I used to spend 10 to 12 hours a day in the penny arcade. The park was always an active scene, always something going on.”

Unlike today’s massive entertainment complexes, Ocean View didn’t start out as a full-fledged “amusement” center. Rather, it grew piecemeal over many years into a collection of fun rides and silly diversions. Ocean View Amusement Park drew curious crowds from its earliest days. In the early 1900s, Ocean View, not yet part of the City of Norfolk, was the end of the line—that is, the streetcar line. People would take the streetcar to Ocean View’s beautiful beach, where they would relax and swim. To help attract tourists, Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO), which owned the streetcar line at that time, starting building rides in Ocean View.

The plan worked: By 1905, people crammed the streetcars, the electric current flashing sparks overhead, bound for Ocean View station. Once there, many headed straight for the beach, but others stopped to enjoy the park’s first major thrill ride, the Figure Eight. Serpentine, as the name implies, and rather tame by modern standards, it was an early roller coaster—though not high. It was replaced within a decade by a much larger roller coaster called Leap-the-Dips—a towering latticework of stout timbers that taunted the timid and double-dared those who claimed to be unafraid.

Otto Wells, a Richmond resident and amusement park entrepreneur, became Ocean View’s second owner. It’s not clear when he took over, but some records suggest it was around 1905. He decided to add “curiosities” to the park to supplement the rides, hoping they would boost traffic. So early park goers rubbed elbows with the likes of Abe Doumar—of Doumar’s Restaurant fame in Norfolk—who on one day in 1907 sold 22,600 units of a new product called an ice cream cone. (Sales were boosted by the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, held nearby.) According to a publication of the Ocean View Station Museum, J.A. Fields, a nationally known maker of amusement park rides, said in 1928 that Ocean View was the most modern and attractive amusement park in the South.

During the Depression, in the 1930s, many amusement parks lost business and closed. Ocean View experienced a slump but held on. Peculiar sideshow acts may have helped. A woman named Rosa Le Dareieux climbed a flagpole at the park on July 1, 1933, and vowed to set a world record by remaining perched atop the precarious roost until Labor Day—a period of more than two months. Thirteen days shy of her goal on August 23, however, storm clouds blew in. As the hurricane of 1933 (they were not named then) roared ashore, Le Dareieux refused to leave her flagpole and had to be rescued by a fireman.

Along with dashing Le Dareieux’s hopes for fame, the storm caused about $200,000 in damage to the park. That and other financial challenges compelled Wells to sell it to VEPCO. Several years later, in 1942, a local optometrist and businessman named Dudley Cooper bought the park. Cooper, a real estate investor, buffed up the place and renewed the side-show oddities that had become an important draw.

World War II and its aftermath proved to be good for business at Ocean View Park. Still, Cooper considered closing the park and developing the land. The brass at the nearby military bases talked him out of that idea. “The Navy was very much interested in [Ocean View] for the recreation of the men who were embarking in this area for overseas duty,” said Cooper in a 1978 interview for an Old Dominion University oral history project. (He died in 1996.)

The park’s success was far from assured. Even Cooper was hostage to the wartime angst that gripped the country during the war. For instance, park administrators erected a 12-foot-high screen along the waterfront and kept the lights low so as not to attract German naval vessels lurking offshore. However, Cooper had civic and military connections—he was a generous donor, a World War I veteran and active in the USO—and he was able to obtain amusement park necessities, such as an intercom system, that would have otherwise been hard to procure in a ration economy.

Young sailors sustained the park for a few years but were something of a mixed blessing. John Campbell, an Ocean View resident who worked as a lifeguard at the park, remembers the volume of sailors that walked to the park from nearby bases. “It looked like a snowstorm, for all the white uniforms around,” he says. The military business was good, but some of the game vendors and live entertainment entrepreneurs began pandering to the baser instincts of the sailors. According to Cooper, the park’s concessionaires, who effectively acted as independent contractors, permitted “a certain amount of gambling in the games” and “introduced burlesque,” a sometimes-risqué variety show.

Some community officials took offense. In a 1946 letter to Cooper, the United Civic Organizations of Ocean View claimed to be “alarmed and aroused over the new low in morality, vulgarity, obscenity, and depravity that has not only been permitted but encouraged” at the park. To his credit, Cooper was likewise disgusted by the offerings of these vendors, even pursuing legal means to try and halt the seedy activity. “I didn’t like the fact that [the concessionaires] were operating rather loosely,” he said. “We got rid of that after two or three years.”

Cooper, the optometrist-turned-budding showman, made the park a popular place through sheer determination. He considered 16 to 18 hours a normal work day, and he enlisted numerous family members to help manage the myriad tasks necessary to operate such a venue, not to mention his optical shops and other investments. The headline for a 1950 feature article on Cooper in The Virginian-Pilot aptly summed him up: “He Deals in Two Kinds of Spectacles.” By the late 1940s, it was typical to see three generations of family members strolling around the park grounds, enjoying all sorts of recreation.

The postwar period was the park’s heyday. There were more than 1 million visitors annually—Ocean View Amusement Park buzzed with activity from Easter until Labor Day. You could fish at the park—it had a pier—and of course go swimming. (In those days, you could rent a bathing suit.) A 1952 advertisement described the park as “Bigger and Better Than Ever! Dancing … Bathing … Fishing … Rides Galore.”

By then there were at least 16 rides, including five for children in “Kiddyland,” and 11 others for older kids and adults. The roller coaster was a favorite among park goers. Daredevils sat patiently as the ride’s heavy chain pulled the boxy cars up 90 feet to the pinnacle of the wooden scaffolding. After a minute of surging through peaks and troughs, windswept riders emerged, emotions plastered on their faces. Some were eager to run back into line for another go; others had had enough of the giant creature. The less adventurous had options, too: They could whirl through the air on the airplane swing or woo potential mates as they floated through the Tunnel of Love.

Performers came in all varieties—human and animal, legitimate and bizarre. Among them were Hal Haviland and His Educated Dog and Pony Circus, a performing bear, Szymonski’s Chimpanzees. An exhibitionist was buried alive in a coffin for more than two months, her only connection to the surface a chute through which she got air and food. A popular high diver named Bee Kyle wowed spectators by leaping off a tall platform and doing acrobatic stunts before plunging into a round, metal, above-ground tank of water—a sideshow classic.

There were competitions, too. Miss Virginia pageants were held at the park. So were contests to find the fattest lady in the park—entrants strutted on stage, their bathing suits ready to burst at the seams. Benny Barry, an Ocean View resident, was a prizefighter at the park’s short-lived but wildly popular outdoor boxing ring. “I fought the first main event down there when it opened and the last main event before it closed,” says Barry, 78, who knocked out a sailor in the second round in the park’s final boxing match, in 1949. Barry recalls looking out at the sea of faces that crammed the edges of the ring. “It was a dollar and a quarter to see the fights, and we really packed them in there,” he says.

For all its gaiety, Ocean View Amusement Park was like many places in the Jim Crow South, a place that denied entry to black people. But Cooper, in a typical show of generosity, used his considerable influence to accommodate the black community as best he could. In 1946, he helped three prominent local African American businessmen open Seaview Beach Amusement Park, located a few miles from Ocean View. Unlike other black amusement parks, Seaview Beach had new rides and equipment and was staffed by blacks from the upper management down, an arrangement impressive enough to earn it a pictorial spread in the August 1947 issue of LIFE. “This wasn’t like many other ventures you saw in the past, where whites manipulated the blacks while the big money quietly [went] to them,” explains Charles Cooper, a Norfolk lawyer and businessman and the younger of Dudley Cooper’s two sons.

In the mid-1960s, with the passage of legislation prohibiting public discrimination, management granted blacks access to Ocean View Park, even though much of society had not yet warmed to the idea. “Even before the time of massive resistance in the ’70s, we integrated Ocean View because it was the law. It was ahead of the curve, but when people asked, we said we had to do it,” says Cooper.

As all sorts of folks streamed through its gates, Ocean View Amusement Park, by all appearances, seemed to be riding a wave of popularity. The rides remained a large draw—especially the Skyrocket, as the roller coaster was called then. Despite its ominous sign—“Last Warning: Do Not Stand Up”—it was the most thrilling minute in Hampton Roads.

Beneath the shiny veneer, however, the grand old park was in fragile condition. The large crowds notwithstanding, it had not been making a sustainable profit since the mid-1960s. The cost of rides and their maintenance had, well, skyrocketed—and so had insurance. Then in the mid-1970s, newer, larger “theme parks” opened in the region—Busch Gardens Williamsburg and Kings Dominion (just north of Richmond), to name two—and people started flocking to them.

In the summer of 1976, crews filmed the first of the two movies to be shot at the park. While the suspense-thriller Rollercoaster was never a great success, the park did get some much-needed rehabilitation and a few minutes of fame.

But it wasn’t enough. The park’s time had passed, and Cooper knew it. He decided to close it in 1978. On Labor Day of that year, Ocean View Amusement Park received visitors for the last time. “By the time the park closed, I was in my 20s,” says Joe Leatherman. “I only went once or twice that last year, and that’s something I’ll always regret. It was a very sad time, because the park was such a big part of the community for 80 years.”

The City of Norfolk bought the park, and part of the sales contract stipulated that the structures had to be removed, save for a few buildings. That left Cooper and his business associates with an interesting dilemma: How exactly does one dispose of an amusement park?

As luck would have it, director Michael Trikilis was interested in filming a disaster movie at an amusement park. When he heard that Ocean View was closing down, he formulated a plan and presented it to park officials. Trikilis would dismantle the park’s most cumbersome facilities—its rides—by blowing them up for his movie, then remove the debris once the fiery scenes had been filmed. It was an ideal plan for all parties involved.

The only snafu occurred when Trikilis called out “action!” for the climatic scene—the explosion that would bring down The Rocket. Demolition experts had rigged the coaster with scores of dynamite sticks and plastic explosives and drenched the framework with 200 gallons of gasoline. The explosion was outrageous—windows in surrounding buildings shattered. But when the smoke cleared, The Rocket was still standing.

A second attempt the same day likewise could not fell the decades-old behemoth. A crowd gathered to watch The Rocket’s demolition turned jubilant, letting out a raucous cheer after each of the failed blasts.

The third one, which came a few days later, got the job done, but only because the demolition crew took additional measures. They sawed through the coaster’s supporting timbers and attached them via cable to a huge tractor, which pulled them from under the scaffolding when the explosion took place.

“What’s interesting is that people were afraid to have their children ride the roller coaster because they thought it didn’t look safe,” explains Charles Cooper. But park employees examined it every day, looking for rot or structural weakness, and there were seldom any concerns. It may have been the most durable coaster in America. “It was so strong, they couldn’t even blow it up,” says Cooper. “It was pulled down.”

Thirty years after the demise of Ocean View, there are plenty of shiny modernist parks with exhilarating rides, sweet treats and the warm breezes of summer. But few are right on a beach, as Ocean View was, and few, if any, shaped a community as it did—in all its shambling, simple glory.