From the end of the era of swing and big bands, a new nightlife scene evolved in Virginia Beach in the 1960s and 70s. A quick history, from the Top Hat and Peppermint Beach Club to Peabody’s and Rogue’s.

The marquee at the Peppermint Beach Club in 1966.

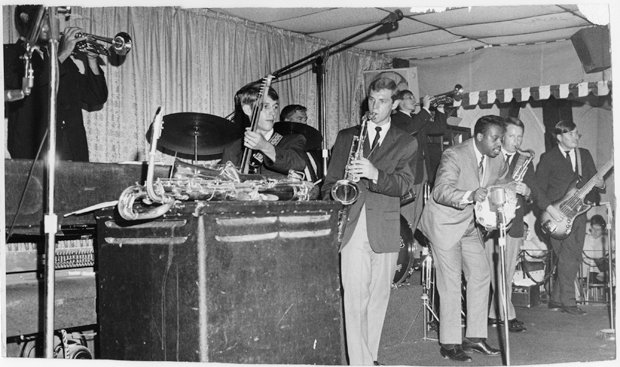

The Rhondels in action at the Pepperming in 1966

Bill Deal in 1962 at the Top Hat

Interior of the Top Hat

A view of the front of the Top Hat

Unidentified girl in front of the Top Hat

It was a different era. The good old days. A perfect time. About the best.

Everyone seems to tell the same stories when they talk about Virginia Beach nightlife during the ’60s and ’70s. They remember the same crowded clubs, the same beautiful people and, most of all, the same music.

For two decades, Atlantic Avenue was alive with music. Crowds of Beach locals, Richmond regulars and tourists from Roanoke and beyond came to dance at the oceanfront. National acts such as Fats Domino, The Platters and The Police played Virginia Beach clubs. Even bigger names like The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix came to the convention center known as the Dome.

The most important band in Virginia Beach was the local group that went national: Bill Deal and the Rhondels. Where the Rhondels went, crowds followed. From The Top Hat to The Peppermint Beach Club to Rogues, the longest lines always formed wherever Bill Deal took the stage.

There were many bands at plenty of clubs—places like The Mecca, The Golden Garter and Peabody’s attracted sunburned beachgoers with fabulously named acts like Pat the Cat and His Kittens. But when people tell the story of Virginia Beach music in its heyday, they talk about Bill Deal and the Rhondels. And those who know the story best remember where it all started—at the Knight’s Club Community House on 18th Street and Arctic Avenue.

In 1959, there was one high school in Virginia Beach, one high school in Princess Anne County, and a few more in Norfolk and Portsmouth, remembers Ammon Tharp, a drummer and singer who formed the Rhondels with the late William Deal. Tharp had been playing in a band called the Saints, at the Seaside Park Ballroom on 30th Street and Atlantic Avenue, but one night he met Deal, then with the Blazers, during a gig at Norfolk’s Admiralty Hotel. The two boys—Deal was 15 and Tharp was 17 years old—hit it off when they realized they both listened to the same soul radio station, WARP 850 AM.

“From the get-go, it was two white guys that liked black music, which in 1959 was hard to find,” Tharp says. “We were white guys playing soul music, that’s what changed us up from the other bands…. They said we were a beach music band because we played on the beach. But we didn’t consider ourselves beach music. We didn’t know what beach music was until 1975.”

Their first gigs were at the Knight’s Club Community House, a teen club where high school students would go to dance. There, the Rhondels developed a core following that would propel them to success at larger Beach clubs and around the country.

“That’s where we developed a relationship with all the kids from these high schools,” says Tharp. “Most kids grow up in their own little neighborhood and know the kids they go to high school with, but because of the Community House we developed this relationship with these people, and still to this day I see a lot of people from those high schools.”

Kathie Moore was one student who first heard the Rhondels at the Community House. She became a lifelong music fan, ended up working for Cellar Door Entertainment and now runs her own band booking agency.

“I don’t think we cared too much, to tell you the truth, about who the band was,” she says. “We just wanted to dance.”

The Rhondels gave the students what they wanted. “It wasn’t us,” Tharp says. “We were just at the right place at the right time.” They played the Community House every Saturday night for about a year. Then, in 1961, they took their first step up—to the Top Hat.

John Vakos, who began running The Top Hat for his father when he came home from the military in 1954, remembers the first time he saw Bill Deal and the Rhondels. “Some kids came in and said they wanted to play. I said, ‘Get on the stage.’ They developed into one of the best bands on the beach.”

At the time, The Top Hat, located on 30th Street and the boardwalk, was one of the best bars on the beach. Vakos had turned a 125-seat, Bob Sheppard-style jazz club into a hotspot where up to 600 people could dance to the hippest music in town.

“I was a young kid, and I knew all the kids, so it was a success,” Vakos says. “Sometimes the audience outside was as great as the audience inside, especially when we had these national recording artists. They would sit on the grass on the boardwalk side…. It was the good old days.”

Big-name bands that played The Top Hat included Roy Orbison, The Shirelles and Gary “U.S.” Bonds. Fats Domino, who Vakos says was the first black artist to play Virginia Beach, came to The Top Hat three times.

During the summer, there was live music at The Top Hat seven nights a week. On the weekends, two bands would alternate from 10 until 5:30 in the evening, then the club would close for a quick cleaning and be back open by 7, when the music would start up again. Vakos says the kids let him know which acts they wanted back, and the bands tried hard to win attention. Occasionally the performers put down their instruments to act out comedy skits. An acrobatic saxophonist from Pat the Cat and His Kittens, out of Binghamton, New York, hung upside down on a trapeze as he played. The crowd was a family crowd—sometimes parents accompanied their children, other times they picked them up when the bar closed at midnight.

Ammon Tharp remembers the family atmosphere well. “On Atlantic Avenue, you’d see people wearing coats and ties, walking with their families. It was just a different era of how people and their families related to Virginia Beach,” he says. “You knew a lot of people in those days, where today you just don’t go down to Atlantic Avenue and see 15 people you know.”

“In those days, there were really good dancers,” Tharp adds. “And people danced—people didn’t get falling-down drunk. It was a good time. People were dancing. It was a perfect time.”

Chester Rodio, who owned The Peppermint Beach Club with Virginia Beach police captain Slick Halstead, also has fond memories. “Everyone dressed up. It wasn’t like today, where everyone runs around real sloppy. Everybody dressed up to come to the Peppermint, and everybody enjoyed it—ask anybody around,” he says. “I knew all the kids that came in there—college kids, local kids, kids coming down from Richmond and Petersburg.” Rodio says his customers dressed in collared shirts and long pants and did not wear flip-flops. Other people remember mini-skirts. All agree the style was neat.

Rodio also owned the Doll House hot dog stand—with the slogan, “From Maine to Miami, from Frisco to Philly, you can’t beat the Doll House for Hot Dogs and Chili”—and in 1969 he would open The Golden Garter, a club that featured beach music until the late ’70s, when its name changed to The Moon Raker, with Las Vegas-style acts like Brenda Lee, Rosemary Clooney and Della Reese. In 1980, Rodio changed the name again, to The Upper Deck, and started the oceanfront’s original 35-plus-item, all-you-can-eat buffet, which is still available there today. A gruff yet charming businessman, Rodio was recognized in 2002, when the Virginia legislature issued a joint resolution “as an expression of the General Assembly’s admiration and gratitude for his outstanding dedication to the business community and his fellow citizens.”

The turning point in Rodio’s career came shortly after he bought into The Peppermint Beach Club, in 1965, when Bill Deal and the Rhondels agreed to leave The Top Hat. “A year after I was there, we put in Bill Deal and that’s what made The Peppermint shoot up,” Rodio says. “After a while, we called it ‘The Home of Bill Deal and the Rhondels.’”

Like The Top Hat, The Peppermint Beach Club had picnic tables on the grass alongside the boardwalk, where crowds could watch jam sessions with alternating bands on weekend afternoons. The Rhondels played six nights a week. Lines out the door—with a cover charge that started at two dollars and went up as the club became more crowded—enabled Rodio to install air conditioning and double the capacity to 1,000 persons. In 1966, The Peppermint began staying open all winter long. “He was the biggest act in town,” Rodio says, his eye twinkling as he remembers working his packed nightclub. “That was about the best. That was my favorite.”

The competition was not so content. Nabil Kassir and his partner Edmund Ruffin, two Virginia Beach lifeguard buddies who already owned a bar called the Tiki and would later run Rogues during its prime, started Peabody’s in 1967. Opening night with the popular Richmond band Joker’s Wild was a hit, but the fledgling club, unable to secure a liquor license, remained second fiddle. “The Peppermint was big, they were the only game in town,” Kassir remembers. “They had Bill Deal and they had a license. It was the premier club.”

For a few years, Peabody’s catered to teenagers, with Motown and Beach Music acts like The Showmen, The Drifters and Percy Sledge. Meanwhile, the downstairs of its old car dealership building on 21st Street and Pacific Avenue was turned into a T-shirt outlet. Starting out small-scale, Peabody’s T-shirt business began printing for other Virginia Beach retailers and eventually grew into a supplier for businesses up and down the East Coast. In the early ’70s, Peabody’s became much busier when it secured a liquor license and brought in a steady stream of local bands like Power Play, Sandcastle, and High and Mighty. Kassir and Ruffin, who had also opened Chicho’s Pizza in 1968, were on their way to becoming dominant players in the Virginia Beach club scene.

First, however, another move by Bill Deal and the Rhondels would rearrange the pecking order. With the 1968 hit single “May I” making the band more popular than ever, Deal left The Peppermint Beach Club at the end of the decade and started playing at Rogues, which he purchased with the local disc jockey Gene Loving (of Whisper Concerts and, later, Max Media) and Richard “Dick” Davis, then the mayor of Portsmouth and later Lieutenant Governor of Virginia. Loving arranged a deal with the label Heritage Records, which would put out about 10 Rhondels records and produced the band’s biggest hit, “What Kind of Fool.”

During much of the early ’70s, Bill Deal and the Rhondels were on the road playing everywhere from Disneyland to New Orleans to Madison Square Garden. By 1975, Tharp says, they had realized, “This is not it, it’s better to be home.” They returned to a different Virginia Beach. Kassir and Ruffin had purchased Rogues and starting bringing in big-time rock and roll acts. The Rhondels returned to The Peppermint Beach Club, where they played until splitting up in 1978. Tharp started his own band—Fat Ammon’s Band—while Deal kept the Rhondels going until 1982, when he went into commercial real estate. (A decade later, Tharp and Deal got back together for one night, and the Rhondels ended up playing their old hits for another dozen or so years until Deal’s death in 2003.)

By the mid-’70s, the “Beach Music” era was ending. Kassir explains how he and Ruffin turned Rogues into Virginia Beach’s hottest club by catering to a growing appetite for rock and roll: “That sound [Beach Music] was dying out. A new sound was coming in. We had changed gears to a new generation of music. Our longevity was the longest for a club that anybody had ever heard of, until the ABC and everybody shut us down,” he says, when authorities closed Rogues. Kassir and Ruffin eventually pled guilty to filing false tax returns. Kassir, after an extended trial, spent one year in prison. Ruffin served time in a halfway house. Today, though no longer partners, both continue successful business careers. Ruffin’s investments include a new Hilton Hotel on 31st Street and Atlantic Avenue (with partner Bruce Thompson). Kassir says he no longer owns bars and restaurants but owns Ocean Horizon Properties. His son is an owner of Peabody’s, Shorebreak and Hot Tuna Bar & Grill, while his wife owns the Italian restaurant Aldo’s Ristorante.

Kathie Moore, who started her oceanfront dancing at the Community House, says that by the late ’70s, Rogues had become a “huge scene.” She remembers some of the best bands played on Sunday nights—her favorites included regional acts like Mother’s Finest from Atlanta and the Mike Latham Band. Bigger names that played Rogues include Van Halen, The Cars, Eddie Money, Herbie Hancock and the Ramones.

Kassir, whose office walls are lined with pictures of him posing with the stars of the ’70s, remembers the scene well. “The crowd,” he says, “was very well dressed. The girls were absolutely gorgeous. We didn’t have behavior problems. It was a beautiful crowd.”

“I think the secret to success was that we gave the people a beautiful location and we had a wonderful staff,” Kassir adds. “We were so well known up and down the East Coast that any tourist knew of us before they came to town …. In the coldest of winter, we almost had a summertime crowd.

Twenty years after the Rhondels first took the stage, the Virginia Beach music scene had matured. Rogues had become the king club, and rock and roll music was here to stay. The sounds of the boardwalk—beach music, soul music, the type of music you can dance to—had become relics of the past. The Peppermint Beach Club closed its doors in 1982, while The Top Hat and the Knight’s Club Community House were already fading memories.