An interview with mountain music virtuoso Ralph Stanley.

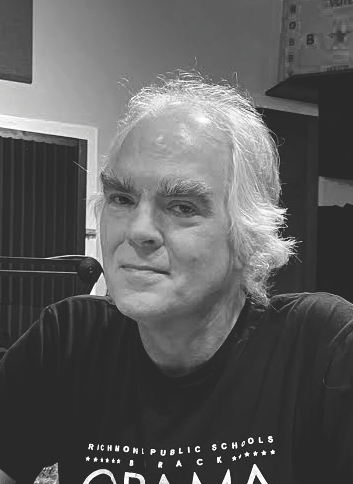

Ralph Stanley

Don Harrison interviewed the legendary Appalachian musician for the June 2008 issue of Virginia Living, and that interview is republished below:

The tourists are taken aback at the impromptu exhibit. They have braved twisting mountain roads to reach the far-southwest Virginia town of Clintwood this Tuesday in March in order to visit the Ralph Stanley Museum and Traditional Mountain Music Center, and there’s the man himself, leaning back in a white rocking chair in the Music Center’s front room. “I’m thinking about doing another recording and doing a lot of religious songs a cappella on it,” the longtime leader of the Clinch Mountain Boys says softly. He’s sporting a sharp, brown western suit and a neatly coifed hairstyle that was probably not acquired in Dickenson County.

For an 81-year-old man who still performs 120 nights a year singing “old timey” music—much of it dating back to the Elizabethan era—Dr. Ralph Stanley is having quite the 21st century. The Virginia Press Association made him its Distinguished Virginian of the Year in 2004, the same year his museum opened. Two years ago, Stanley (who holds an honorary doctorate of music—hence the “Dr.”) was awarded the National Medal of Arts, the nation’s highest honor for artistic excellence. This year, Virginia lawmakers designated the banjo player the Outstanding Virginian of 2008.

The shower of recognition comes on the heels of his Grammy-winning work on the soundtrack to the 2000 Coen brothers film, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, which sold an amazing six million copies. The disc not only brought Stanley’s ageless mountain music out into the mainstream, it also reintroduced the pioneering harmonies of the Stanley Brothers—the matchless bluegrass act he led with his older brother Carter from 1946 to 1966—to a whole new generation of listeners.

The Ralph Stanley Museum is where to learn more, a “Crooked Road Heritage Trail” venue funded by grants from the Appalachian Regional Commission and the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority. The exhibits in this renovated former funeral home chronicle Ralph’s (and Carter’s) story through interviews, rare sound recordings, vintage photographs, little-seen video footage and, of course, that growing pile of awards and accolades.

I had been warned that he was a “hard” interview, that he didn’t like to talk much, but I found Ralph Stanley to be warm and charming during our hour-long conversation at the museum. He sat downstairs with me in a pair of rockers and patiently answered questions while the sounds of his life wafted through the air.

Where were you born?

About 10–12 miles from here, in a little town called McClure at a place called Big Spraddle, just up the holler. I was born in 1927 and moved to where I live now, where I was mostly raised, in 1936.

Was there a lot of music around your house growing up?

No. My daddy [Lee Stanley] didn’t play an instrument, but sometimes he would sing church music. And I’d hear him sing songs like “Man of Constant Sorrow,” “Pretty Polly” and “Ommie Wise.”

When did you get your first banjo?

I got my first banjo when I was a teenager. I guess I was 15, 16 years old. My aunt had this old banjo, and Mother bought it for me … paid $5 for it, which back then was probably like $5,000. [My parents] had a little store, and I remember my aunt took it out in groceries.

Your mother Lucy taught you the banjo?

Yes. She had 11 brothers and sisters, and all of them could play the five-string banjo. She played gatherings around the neighborhood, like bean stringin’s. She tuned it up for me and played this tune, “Shout Little Luly,” and I tried to play it like she did. But I think I developed my own style of the banjo. …

Who influenced your banjo playing?

Well, I liked Earl Scruggs [who started with Bill Monroe and later formed Flatt and Scruggs], and I heard Scruffy Jenkins. But there’s no doubt Earl’s the best banjo player I ever heard. He knows his neck, knows how to use his fingers and his picks. He’s just a natural. But I didn’t want to sound like Earl.

You have different styles.

There’s three styles: There’s Don Reno’s style, there’s Earl’s style and then there’s my style—the Stanley style.

Explain how your banjo playing is different.

My sound is more down-to-earth, more simple. I play the tune closer than most people. There’s lots of different ways you can play an instrument … . I try my best to play the melody and to make my banjo sound like I’m singing.

Did your brother Carter start playing music first?

We started about the same time. We had a radio and liked to listen to the Grand Ole Opry. Before we had instruments, Carter and I used to take sticks and act like we were playing along, you know—never did get a sound out of it [smiles].

Who did you like on the Opry?

Well, Bill Monroe was always my favorite. And the Carter Family, they lived not far from where we were raised … .

You both served in the Army, right?

Carter went before me. I graduated from high school and served in the Army during [the end of] World War II. I graduated on May 2, 1945, and I was inducted on May 16. Stayed little more than a year.

And you immediately began performing when you got home?

Yeah, my daddy and Carter picked me up from the [station], and Carter was playing with another group, Roy Sykes and the Blue Ridge Mountain Boys, and they had a personal appearance that night. So I sung a song with Carter on the radio before I even got home. The next day, I joined the band, stayed with them about three weeks. But I wasn’t satisfied. Something didn’t feel right. So I told Carter that if he wanted to start up a show, start up a band, together, that was fine. If not, I was going to start taking a course … I had veterinary on my mind. I was always good with animals. But I’m so glad I didn’t. See, God knows more than I do, or you do.

The Stanley Brothers started winning over audiences immediately. Where did your sound come from?

It’s just a gift. Some don’t find it, some do. I think everybody is equal but with a gift.

You two became one of the great harmony duos. What’s the secret to harmonizing?

It’s just knowing what you are doing, I guess. You have to have an ear for it. We played by ear, and I’ve always played by ear. To know when you’re flat and when you’re sharp and make it blend together—that comes with your gift.

The Stanleys began playing on local radio stations, first at Norton’s WNVA.

Yes, but we didn’t stay long there. After a couple of weeks, we moved to Bristol and WCYB to start this show, Farm and Fun Time. We stayed there off and on for 12 years.

In those early days, did you know anything about the entertainment business?

Not a thing. When we first started, our fiddle player, Leslie Keith, he was something like 35, 40 years old at that time and had been in the business all his life. He traveled with us, taught us a lot.

Did you have a manager?

Didn’t have a manager. I’ve never had a manager. I’ve had bookers, you know, but never had a manager.

Your brother was revered for his singing, but he also wrote a lot of the early Stanleys material.

Carter was a great lead singer, and he was a good songwriter too. We did a lot of Bill Monroe music when we first started, but we soon found out that didn’t pay off—we needed something of our own. So we started writing songs in 1947, 1948. I guess I wrote 20 or so banjo tunes, but Carter was a better writer than me.

Is it true that Bill Monroe broke his contract with Columbia Records because of the Stanleys?

Yeah, he told ’em if they signed the Stanley Brothers, he’d leave. So he went to Decca [another label]. I don’t know what he was upset about. I never figured that out [smiles].

He’s considered the father of bluegrass.

Oh, he was the first. But it wasn’t called bluegrass back then. It was just called old time mountain hillbilly music. When they started doing the bluegrass festivals in 1965, everybody got together and wanted to know what to call the show, y’know. It was decided that since Bill was the oldest man, and was from the Bluegrass state of Kentucky and he had the Blue Grass Boys, it would be called “bluegrass.”

For a brief time, the Stanleys split up and your brother ended up singing in Monroe’s band.

That was ’50, ’51. Things had got lean, you know [with bookings]. Bad weather and all. And Carter had always wanted to sing with Bill Monroe, so we decided that we’d rest for a few months. So he went off with Bill to sing.

It’s interesting that Monroe would be mad at the Stanley Brothers and then hire Carter for his band.

He knew Carter would make him a good singer. I also played with Bill a few times back then. Oh, Bill Monroe loved our music and loved our singing. He became one of our best friends. That ended all of that stuff. I never had a better friend than Bill Monroe.

When the Stanleys recorded for King Records in the late ’50s, your sound seemed to change.

It went more to a “Stanley style,” the sound that people most know today. Syd Nathan [King’s owner], he loved the guitar and he wanted us to get a guitar to replace the mandolin. He said, “That’ll separate you from everyone else.” So we got George Shuffler. He’s the man who stayed with us [on guitar] for 17 years.

King Records was certainly eclectic—it had the Stanley Brothers and James Brown.

Yes. You know, James Brown and his band were in the studio with us when we recorded “Finger Poppin’ Time” [a 1960 cover of an R&B song by Hank Ballard]. James and his band were poppin’ their fingers on that.

In 1958, the Stanleys relocated to Florida. Why?

Well, we wore out [this area]. I mean, you can get tired of chocolate pie. So we thought we’d hunt out some new territory. Jim and Jesse [the celebrated bluegrass brother act from nearby Wise County] had a Jamboree down in Live Oak, Florida. They left and we decided we’d go down there and try our luck. I ended up living in Florida for 10 years. We hooked up with a sponsor, Jim Walter Homes, and did a TV [show]. They put us on in Jacksonville, Tampa, Ft. Myers, Tallahassee … so we had a weekly tour of four or five nights a week there. We did that up until Carter passed away [of liver cancer], in 1966.

You must have been devastated.

Oh yeah. He’d been failing a year or so. I knew it was coming.

And he was the focal point onstage.

He always did the emcee work. But, you know, in his last year, he would go off of the stage after four or five songs and just leave me and the band out there, so I had to talk or let it go blank. I believe that he did that for a purpose, figuring that I’d need that [experience] sometime.

Was it a hard decision to continue on your own?

I was worried, I didn’t know if I could do it by myself. But boy, I got letters, 3,000 of ’em, and phone calls—people told me, “We’ve been Stanley Brothers fans through the years, now we’ll be yours.” And that really helped me. So I just fell right back in. I went to Syd Nathan at King and asked him if he wanted me to go on, and he said, “Hell yes! You might be better than both of them.”

When did you discover Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley?

I met them around 1969 at a place just over the river in Louisa, Kentucky. I had a flat and was late for a show, and when we did get there, I heard some singing going on and it was Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley. They were about 16 or 17, and they were holding the crowd ’til we got there. And that’s how I met them, they were singing. They sounded just exactly like [the Stanley Brothers]. I saw a potential in them … I hired them and put them in the band, even though that made seven. [I wanted] to give ’em a chance.

When did you first get into politics?

It was about 1970 here in Dickenson County. I run for Clerk of Court and the Commissioner of Revenue. What happened is, somebody traded me off—they used my popularity and money to elect somebody else. I was done dirty. And I’m so proud that I was done dirty, because if I had been elected, I wouldn’t be here talking to you today.

You think you would’ve become a full-time politician?

Well, I woulda had a job to do … maybe woulda finally quit [music]. So that’s one time I was done dirty and I want to thank them for it now.

Tell me about your participation on the wildly popular O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack.

That put the icing on the cake for me. It put me in a different category.

Your version of “O Death” made for the movie’s most memorable scene. How did it come about?

T-Bone Burnett [the soundtrack’s producer] had several auditions for that song. He wanted it in the Dock Boggs style [Boggs was a legendary Norton banjo player who recorded the song in 1963]. So I got my banjo and learned it the way he did it. You see, I had recorded “O Death” three times, done it with Carter. So I went down with my banjo to Nashville and I said, “T-Bone, let me sing it the way I want to sing it,” and I laid my banjo down and sung it a cappella. After two or three verses, he stopped me and said, “That’s it.”

You like to sing a cappella.

I went to the old Primitive Baptist Church as a boy, and that’s the way they sung—no music. They still don’t allow instruments in that church. The members will buy every tape, CD I make but they won’t have it in the church.

How is your solo work different from the Stanley Brothers’?

I think I took it a little further back. Down to earth. Carter liked to look out, you know, do more up-tempo. But T-Bone Burnett told me that I went backward to go forward. That’s his statement, not mine. I knew if I changed anything, it would be to go back further. To the old-timey. That’s what I did, and I think it paid off. While I was doing that, all these other people were trying to experiment with a lot of new sounds. But I kept mine.

What do you think of today’s bluegrass music?

It’s fine but it’s not my favorite kind of music. When you hear me come on the radio, you know who it is. When that comes on the radio, you don’t know. Maybe it’s supposed to be like that, and I don’t have a thing against it. There’s room for all.

One thing that has always struck me is how generous you are onstage to your band.

I like to give all of them a chance. I’ve had the same band for 15 years. All except the fiddle player who passed away, Curly Ray Cline. My current fiddle player has been with me about three years. My son, Ralph II, is with me, and my grandson Nathan has been with me for two or three years. Ralph II has put out about five CDs of his own, and he’s been nominated for Grammys. I don’t think he’s won one yet, but there’s still time.

Is it still fun for you to play music?

It’s a job, but it’s always been a job. It’s not like real hard work, but it’s still work.

Why not retire?

Well, you never know what might happen, how long you’ll be around, or what you might need. And Ralph II and Nathan, I want to give them all the exposure I can. That’s the main reason. And, you know, I like home fine but I’m so used to being on the road … .

When did you get married?

I got married in 1968. I had girlfriends along the way, but I got the one I wanted [Jimmi Stanley]. Met her in Cincinnati … Kentucky girl.

Was she a bluegrass fan when you met her?

Back in the Elvis days, she liked that rock ’n’ roll. But deep down she was a bluegrass fan. She likes to listen to Carter and me together. She thinks my own stuff is fine, but she likes the Stanley Brothers.

How does it feel for you to be sitting in your very own museum?

It’s hard to describe. I never expected this. I was really tickled and pleased when it happened. Most people are dead and gone before they see their own museum.

Well, most people don’t get one.

I know, and I’m so very proud and thankful.

This article originally appeared in our June 2008 issue.