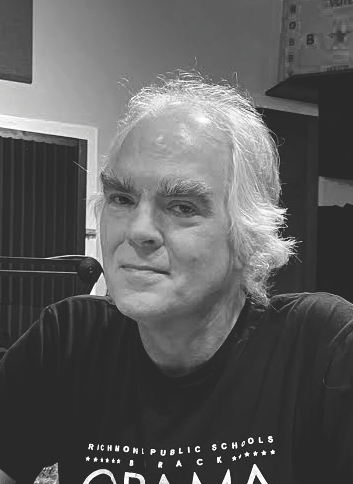

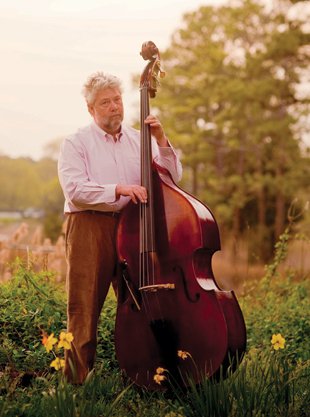

Jazz legend Lonnie Liston Smith about growing up in Richmond, being scolded by Miles Davis and new talent.

Lonnie Liston Smith

Photo by Adam Ewing

Lonnie Liston Smith (born 1940) comes from a distinguished Richmond musical family. His father, Lonnie Sr., was a longtime member of gospel’s Harmonizing Four; brother Ray was one of the founders of the Jarmels singing group; and brother Donald is a collaborator and accomplished pianist, flautist and singer who’s also worked with Dizzy Gillespie and Benny Carter. “I started playing in a band in high school,” says Smith. “One day, someone played a record by Charlie Parker and I said, ‘Man, what is that?’ It was so beautiful. I mean he was playing jazz and improv, and I was like, ‘Man, that’s what I want to do.’”

He attended Baltimore’s Morgan State University, sharpening his jazz knowledge in area clubs, and, early on, scored high profile gigs with drummers Art Blakey and Max Roach, saxophonist Rahsaan Roland Kirk and bandleader Pharaoh Sanders. Later, Miles Davis would come calling. Smith also discovered the Fender Rhodes electric piano, his instrument of choice, and made his debut as a leader in 1972. It was the 1974 LP Expansions that changed his career; it was a crossover jazz-funk smash, yielding prominent samples in later years from artists such as Mary J. Blige and Jay Z. Still living in the Richmond area, Smith tours constantly, mostly overseas.

Although his name never entered the musical mainstream, unlike jazz greats Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane, Richmond pianist Lonnie Liston Smith may be the genre’s most important living innovator hailing from Virginia. After his move to vibrant New York City in 1963, then ground zero of modern jazz, he worked with stars like Betty Carter, Roland Kirk, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Gato Barbieri and Pharoah Sanders until in 1972 Davis offered him the piano chair in his electric jazz formation. For Smith, that was his breakthrough and after a year he embarked on his journey as a leader of the Cosmic Echoes, cutting a series of successful albums for the Flying Dutchman label while pioneering the sub-genre cosmic jazz, also known as spiritual jazz, and jazz-funk. At 77, and back in his hometown Richmond, Smith still has a worldwide following and frequently tours in Europe and Japan. We chatted with him about the Richmond jazz scene today and yesterday as well as his work with Miles Davis.

Richmond’s jazz scene is on the upbeat, but it’s still a far cry from how it used to be in the 1950s and 1960s. Take us back.

Especially when I was growing up, we had 2nd Street and Hippodrome Theater, and that was very famous. The musicians called it 2-Street. That’s how I met [jazz singer] Billy Eckstine. I was on tour with our all-star group and I thought how could I just hang out with Billy? Billy Eckstine heard me talk to his musical director and I said, yea, I’m from Richmond, Virginia, and he came right into the dressing room and started talking about 2-Street. Because him and Sarah Vaughan and Duke Ellington used to work at the Hippodrome Theater. And we had The Mosque [today Altria Theater.] Back then there really was a lot going on, music wise. And of course my father had the famous gospel group, the Harmonizing Four, and I met all of the great gospel artists because they’d come right by the house. All of them, James Cleveland, Mahalia Jackson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, she was here in Richmond. She did a lot of work with my father’s group. Music was really happening back then.

In the early 1970s, you joined Miles Davis’ group and you stayed for a year.

I really enjoyed working with Miles Davis, that was like the epitome because if people do their research, they find out that all the great jazz musicians that they are listening to today came out of what we called the Miles Davis University. When you performed with Miles Davis, it was amazing. Because very few leaders create every night. Miles didn’t want the same thing every night. He wanted you to be very spontaneous and creative. That’s hard to find today. When you left Miles’ band, you automatically became a leader. Because he was always testing you and he was always very candid and very real, on the stage and off the stage. He never held back, he always spoke exactly what he meant. I had a lot of fun with Miles, he used to always tease me. He used to say, “you’re too nice.”

But Miles wasn’t the easiest boss to work for.

The only time that I saw he got really angry with me was when he wanted a certain sound and he dropped his hand on my keyboard. And I said, “Miles, what chord is that?” And he said, “well, when you find the piano player in my band, ask him what chord it is.” Of course the piano player was me. I didn’t ask him any more questions. But he was definitely a genius.

In 1988, you moved back to Richmond. What are your thoughts on your hometown’s jazz scene today?

Lately I have been running into a lot of younger musicians that are very inspiring. I met a group called Butcher Brown, and they are excellent. I met a pianist called Ayinde [Williams], he’s really gonna be something one day, he’s very talented. I’m really inspired inspired by all these young musicians that I’m hearing. For a while I thought that things were falling off. But there are a lot of young musicians and great talent still here in Richmond. So we are gonna see how things will grow.

Click here to read our feature about the full history of jazz in Virginia: meet the artists, read profiles and watch performance videos and interviews.