The history of a place isn’t just about what’s documented in books and on display in museums.

Another world is often overlooked— throughout the urban and rural landscapes, in towns, cities, and neighborhoods.

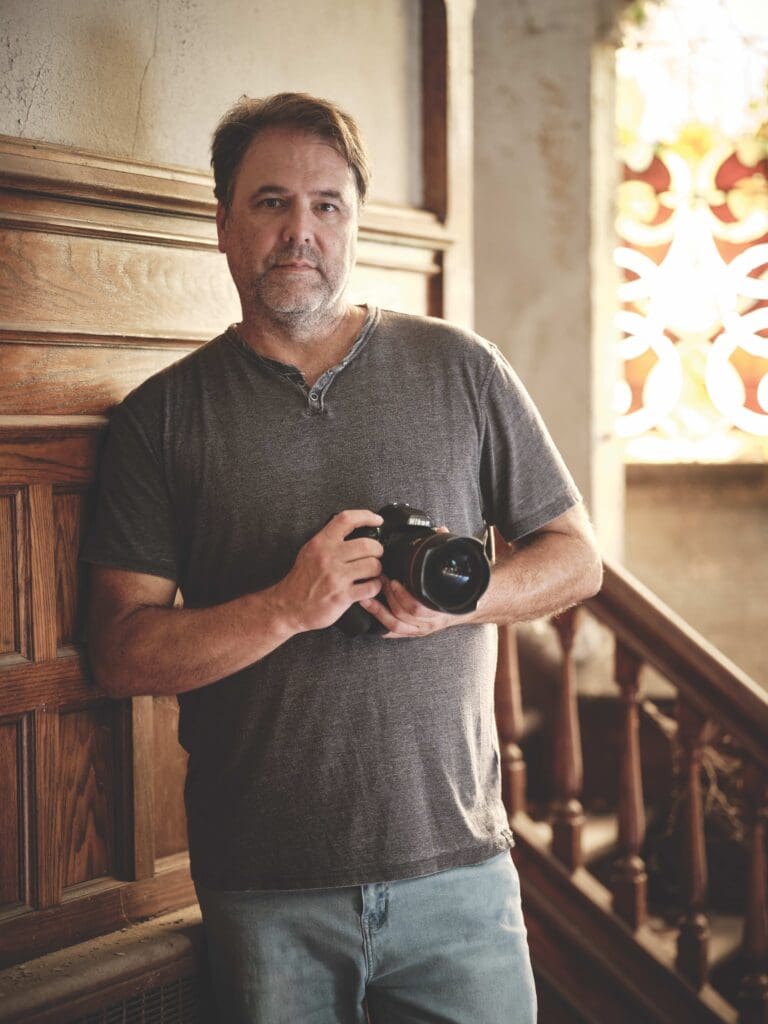

They’re the churches and homes, the town halls and schools, once epicenters of family and community life all over the Commonwealth, that have been abandoned. Now, they’re skeletons of what once was, nearly unrecognizable, with peeling paint, sagging roofs, and broken windows—shells of a past life, often with no one left behind to tell their stories. But to photographer John Plashal, these abandoned places are magical. “There’s nothing prettier,” he says.

The Richmond-based photographer remembers the first time he knew he’d caught lightning in a bottle, when he stumbled on two crumbling schools, long abandoned, that stopped him in his tracks. He was exploring Powhatan and came upon what turned out to be Belmead on the James and two historic schools that once occupied the land. “Some say that the land whispers to them through their feet,” says Plashal, “and that certainly happened to me.” He was so moved that he grabbed his camera and started shooting.

After a bit of detective work, he discovered that the schools were started in the late 1800s, specifically to educate Black children— St. Emma Military Academy for boys and St. Francis de Sales School for girls. The fact that

both were on property that was once a plantation was a powerful irony. “The fact that almost 15,000 African-American students were educated on the grounds of a former plantation is a story that needs to be told,” he says, adding that he has initiated coverage on local news stations, as well as CNN and CBS. It’s been a gratifying journey for Plashal, and it all began by committing a crime: trespassing.

That fateful day was a turning point for Plashal, who has spent the last 13 years chronicling what many people find easy to drive by, to overlook. He calls his work “Beautifully Broken Virginia”—also the title of his 2019 book—where he captures the soul of structures through his camera’s lens. From churches to mansions, asylums, prisons, and restaurants, they’re all abandoned. Mother Nature is doing her best to reclaim them—“it’s like she has a sixth sense,” he says—as vines snake through cracks in walls and tangled weeds consume walkways. Tree seedlings sprout from roofs and weeds choke erstwhile gardens.

He explores hollow husks that reveal little of what they once were, as well as the gorgeous, ornate mansions, crumbling and dilapidated, that might contain a host of artifacts about lives left behind. A pair of shoes, a suitcase, a newspaper, photographs are some of the clues he finds in the structures he explores—as if someone ran an errand and never came back. While hints might surface, they trigger even more questions that go unanswered. Hamilton High School in Cartersville was shuttered 60 years ago; its last class was dismissed in 1964. Now, its 250-seat auditorium sits empty, layered in dust and memories. What plays were performed on that stage?

its finest. Details include stained glass windows, carved wainscotting, an intricate altar, a chancel rail, and gothic-inspired arches, windows, and columns.

Sometimes Plashal is rewarded by meeting people connected to the abandoned properties he shoots. He does this through practiced, down-home sleuthing, which he accomplishes by spending time in the communities he explores. “I interview loggers, bribe firemen with donuts, initiate conversations with locals in diners, and approach patrons at gas stations,” he says. “Many times, I’ll just knock on doors. Rural Virginians are super friendly. All they want to do is accommodate me, especially when they realize my intentions of learning about their community in genuine.” And when he meets someone who actually grew up in a house or worshipped in a church or attended a school—“that’s the icing on the proverbial cake,” Plashal says, flashing a confident smile.

Richard Avedon photographed models, Ansel Adams, the landscape—all images of conventional beauty. But think of Plashal as being more like Diane Arbus, who captured those on the fringe, people who were shunned and not revered. Through Plashal’s lens, beauty is in the unconventional. His work introduces us to parts of our communities that otherwise go ignored. And now, in a world in which TikToks and Instagram posts set expectations unrealistically high—for what we see, how we look, and what we consume—he reveals the beauty in what’s broken.

A Journey Through Virginia’s Abandoned Afterworld

John Plashal has a corner on eerie Virginia as well as an emotional connection to the subjects he photographs—the diners, asylums, churches, schools, and homes he has discovered all over the Commonwealth. He says they represent Virginia’s “abandoned afterworld” that offer intriguing and cryptic clues about the people who once thrived in these forgotten and decaying places. His attachment to these

structures drove him to commemorate their unique appeal through A Beautifully Broken Virginia, his 120-page art book with 80 powerful and haunting images he’s managed to capture throughout the dozen years he’s been roaming the state. Listen to his podcast, dive deeper into “extreme landscape photography,” learn about upcoming shows and lectures, purchase prints, and more at JohnPlashalPhoto.com.

This article originally appeared in the October 2024 issue.