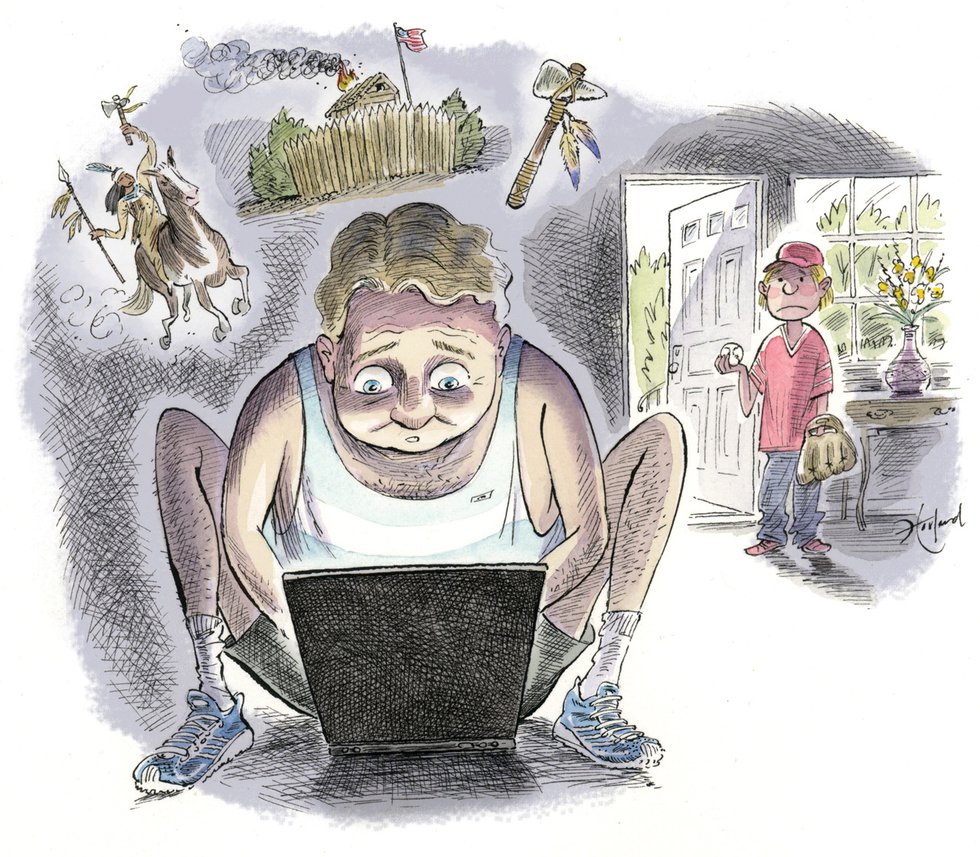

Alt-facts, fake news, obsession and wasted days in the land of the dead.

The sunny spring weekend morning beckoned me. I would start jogging again and the inflating tire resting on my belt would turn to washboard, and I would become that dad I imagine I had been in my 30s who bounced down roads and across ball fields and impressed my boys and their friends and my wife, and surely, somewhere in some hidden den of iniquity in their minds, her girlfriends.

I teased my wife for sitting there on the couch staring at her smartphone: “You’re like the kids.” Without looking from her phone she said, “I’ve found a new line of my great-grandmother’s family. This Mormon site is amazing.”

Don’t say it, dear. Don’t. Please. But she did. “Come here and look. It’s fun.”

Already knowing that the LDS folks are the rock stars of genealogy, I couldn’t help but look at their website database. “Enter a name,” my wife directed. I entered the name of my grandfather on my mother’s side who had died the month before I was born in 1967. There he was, Wilbur Fred Schock. Then I clicked “Fan Chart.” In a new window fanning out from his name appeared the names of his parents and grandparents and great-grandparents. To the far left were two of his great-great grandparents, George Schock and Elizabeth Seibert. I clicked on her name. Her father’s name was Christian Seibert. I clicked on his name. Up came his parents, Susanna Fishback and Capt. John Jacob Seibert (or Seybert), who the site says died in 1758 at Fort Seybert, Colony of Virginia.

“Weren’t you going to run?” my wife asked.

“My people are in Virginia in 1758! This is amazing!” I answered.

When I went to FindAGrave.com and searched “Fort Seybert,” up popped the following information: “This is a mass grave for those who died at the hand of Killbuck and his men in April 1758.” Capt. Seybert and his wife, Maria Seybert, another story explained, were among nearly 30 people who surrendered when promised they would not be harmed. The warriors proceeded to bind up 10 of the adolescents and children, then execute the adult men and women. According to the site, Christian Seybert (later Seibert), along with several other Seybert children, was one of the children abducted. Days after the event in present-day Pendleton County in eastern West Virginia, a 24-year-old colonel, George Washington, wrote from nearby Fort Loudoun (near Winchester) to John Blair, governor of Virginia, informing him of the slaughter and his despair for not having “time enough to avert it.”

“Are you going to eat lunch?” My wife asked. “I’m not hungry,” I said.

I bound up the stairs to where my youngest son was playing Call of Duty and told him his great-great-great-whatever grandpa was abducted by Shawnee and lived with them for years.

When I returned to the couch and the laptop my wife warned me to be careful. These online genealogies are very often inaccurate, she has discovered during her own arguably obsessive searches, glued together by amateurs with spotty information likely recorded by other amateurs, many of whom connect dots more with hopes than well-vetted documentation.

But that afternoon, I kept reading. I wondered if, somewhere in my genetic material or some shared subconscious memory, this tale lived and was part of me. I searched on.

Amid all the digging I occasionally retraced. Around 4 p.m., I finally noticed a detail I had blown past several times. The LDS site had listed Christian’s parents as Jacob Seybert and Susanna Fishback. But, according to all other accounts, many of which were based on significant source material, Jacob’s wife and the mother of all the Seybert children was Maria, who died in the massacre.

But Christian is listed on the “Find a Grave” site as one of Jacob and Maria’s children who was abducted. I rechecked the source of that material.

None was given.

I went looking for sourcing closer to the event. None of the stories within a century of the massacre mention Christian. At 8 p.m. (too dark to run now) on page 30 of a 45-page book called The Seiberts of Saarland, Pennsylvania and West Virginia by Raymond Martin Bell, I found clarity in the confusion. In fact, Bell, the author of numerous books who provided source material for all of his assertions, wrote several paragraphs in the book specifically to address generations of questions about the Jacob Seybert clan. It turns out that Christian was actually the son of Jacob Seybert, son of Christopher, a cousin of Capt. Jacob Seybert, who died in the massacre in 1758.

Christian, my grandpappy to the whatever-power, was 150 miles northeast in Pennsylvania learning to make and mend shoes at the time of the massacre.

“I’m sorry,” my wife said as she headed up to bed.

I had been enjoying my story so much. I had been excited to spread the news. I imagined that around some campfire someday I would tell my grandchildren the great story of our ancestors and the horrific slaughter and the remarkable frontier tale of children their age taken into the woods to live among the Shawnee and Delaware.

Instead, I was left with only the three words I’m most tired of saying to my wife: “You were right.”

This article originally appeared in our June 2017 issue.