“Virginia has so much to offer,” says Jay Fleming, who has a particular affinity for the Chesapeake Bay.

The photography phenom has been in the water, his camera in tow, since he was a teen. The Annapolis native “fell in love with the Bay,” he says, adding that being around water is something he comes by naturally.

His father, Kevin, is an award-winning National Geographic photographer, who’s worked all over the world. “He’d sometimes take me on assignments when I was a kid,” says Fleming, who inherited his father’s hand-me-down Nikon when he was 13 and never looked back.

From fishermen to underwater creatures to boat bows, the younger Fleming has found his stride photographing the world of water, much of it around the Chesapeake Bay—its waterlife and wildlife, its vessels and industry, its coastal communities and dwindling cultures. His photography workshops are wildly popular, selling out as soon as they’re posted. From a few days on Smith Island spent in search of pelicans and egrets, to a week on the coast of Maine photographing lighthouses, to a photo trip to the Galapagos, Fleming shows aspiring shutterbugs the ropes. “I like connecting with people,” he says.

Fleming will do just about anything for the shot—including rising well before dawn or spying on crabs in their grassy aquatic homes. And then there was the time he jumped into a pound net, neck-deep in menhaden, to get their perspective of the fishermen—from the perspective of the fish, that is. “Boat, kayak, in the water, or even underwater—you have to be willing to do whatever it takes to get the shot,” he says.

He chronicles his work through gallery shows and images he sells on his website. There are also calendars and two books, the latter rich in images and words that have become coffee table staples among his fans.

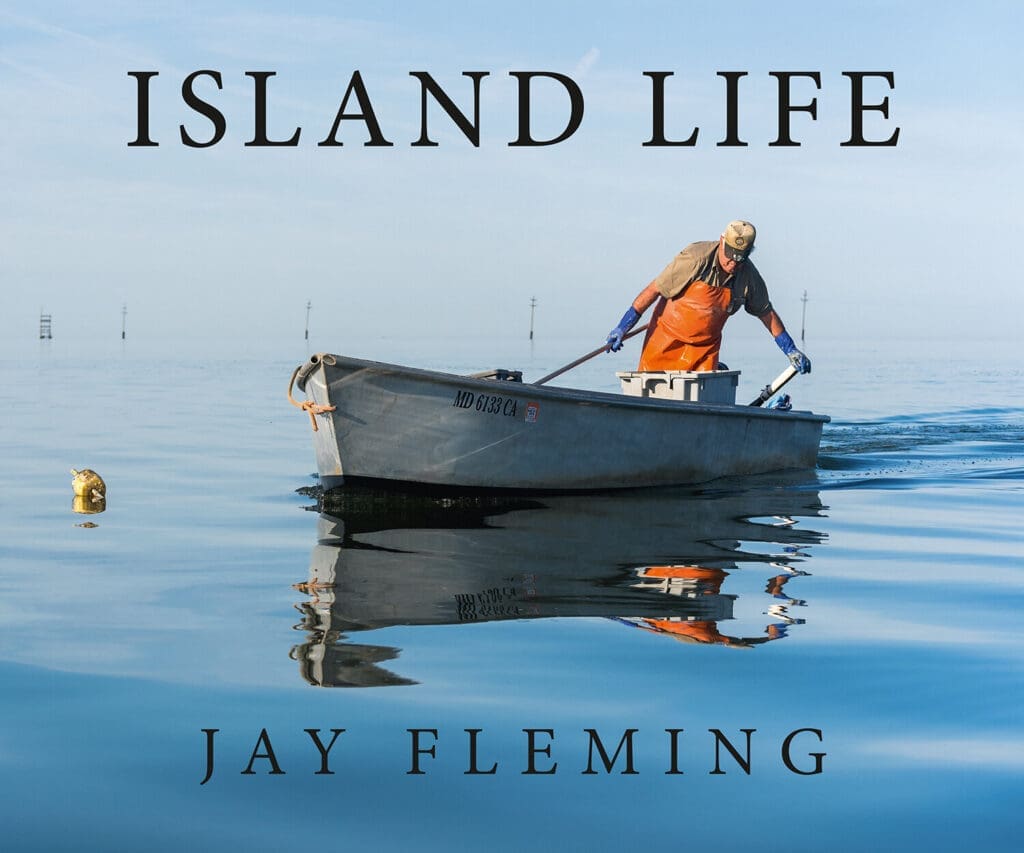

In his most recent, Island Life, he documents the sinking island of Tangier, home to just over 400 people. It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of the island’s landmass has disappeared, displacing nearly 75 percent of its once robust population (for an island) and decimating the livelihood of the crabbers and pickers and fishermen who have lived there for generations. Working on Water, his first book, documents the Bay’s bounty through the watermen, seascapes, and workboats of the region’s seafood industry. He can practically operate his media empire from a boat, where he shoots and posts and watches his Instagram grow. He has nearly 50,000 followers.

Fleming often gravitates toward the theme of change. His images of the Bay’s barrier islands illustrate their uncertain future, with rising tides and shrinking populations. He captures weathered women in their kitchens and living rooms—the crab pickers—who “process” the harvests by hand from the crabbers, usually their husbands and other family members. And he chronicles the effect the wind and waves have had on the forgotten and abandoned ships and the homes that dot the coastline. “I tend to find subjects that are either changing or on the verge of change,” he says, adding that the fishing industry and Tangier Island are prime examples. “I noticed that kind of stuff changing,” says Fleming, adding, “I realized once it was gone, it wasn’t going to come back.”

JayFlemingPhotography.com

From the once-robust industries that dotted the Chesapeake Bay’s coastal communities to the disappearing populations of vanishing island communities like Tangier and Smith, Jay Fleming has documented the changing tides of these working waterfronts, revealing both the beauty and perils of a way of life that is constantly changing and challenged by the rhythms of the tides. For a deeper dive, explore Island Life, by Jay Fleming (2021).

Jay Fleming

I tend to find subjects that are either changing or on the verge of change. I realized once it was gone, it wasn’t going to come back.

From ibis, pelicans, and egrets, to blue crabs, shellfish, and terrapins, the marshes and underwater grasslands of the Chesapeake Bay provide habitats for a plethora of important species. Shallow waters around islands and shores are home to submerged meadows of eelgrass and widgeon grass that provide ideal nurseries and hiding places for dozens of creatures. Vegetation not only offers habitat, but it also oxygenates the water and provides erosion control by suppressing wave energy before it reaches the shore.

This series was inspired by a Wooden Boat magazine project in Maine, where Fleming was on assignment to photograph a sailing dinghy. A simple image of Sjogin’s bow led to “Boat Bows,” one of Fleming’s most dynamic and popular series. Since that original assignment nearly a dozen years ago, Fleming has photographed boat bows all over the world, constantly adding images to the series. “The conditions have to be perfect,” he says, adding that he’s discovered secret locations all over the Bay where the horizon meets the water, setting just the right stage.

Jay Fleming

Boat, kayak, in the water or even underwater—you have to be willing to do whatever it takes to get the shot.

Included in Jay Fleming’s “Boat Bow” series, this bow is from a dory in the Penobscot Bay in North Haven, Maine.

Fleming photographed this double-ended canoe in Brooklin, Maine.

“Jaws,” a lobster boat in Vinalhaven, Maine. Fleming leads photography workshops in New England that immerse participants in the lobster industry and coastal life.

This article originally appeared in the August 2024 issue.