Virginia’s honeybees survive with a little help from their friends.

Photo by Kate Thompson

A visitor turning onto the dirt lane that leads to Lucky Streich’s 140-acre spread can’t help but notice a cautionary “Bee Crossing” sign and an assortment of colored boxes lined up on the left, swirling with buzz and hum. Welcome to Bee Haven Apiary.

“My wife wanted to get into a hobby,” the stocky and gregarious 56-year-old says, wearing shorts and flip-flops on a warm October afternoon. “She went to the beekeeper and started with two hives. I started reading up on bees and thought, ‘These things are pretty doggone cool.’ Needless to say, now, I’m full force in it.”

The couple currently has “63 or 64 hives” on their Southampton County farm, and Streich is always looking for more. “If it’s a bee, and I can get it, I’m gonna get it,” he says. With tools and heat gun in hand, Streich (often with wife Amy in tow) will come to your infested chimney, under-house, or tool shed and do what is called a “cut out”—capturing the queen bee of the wayward colony and persuading thousands of angry drones to join her in a wooden box ready for transport.

Photo by Kate Thompson

The Streichs are part of a growing number of Virginia backyard beekeepers helping pollen-loving Anthophila—and in particular the much-needed honey bee—to survive in an ever-changing, tumultuous climate. “The numbers of bees have been going down dramatically since the 1970s,” says Keith Tignor, Virginia’s state apiarist. “We estimate that we have had as many as 85,000 to 90,000 beehives across the state, and now we’re looking at 35,000, maybe at best 40,000, hives.” The die-off is part of a nationwide trend known as colony collapse disorder, he adds, and this past season was Virginia’s worst in a long time. “We lost 60 percent of our managed colonies this past winter.”

In response, Tignor’s office announced a program that would provide three hives, free of charge, to interested Virginia residents 18 years or older. The program received so many applications that it quickly ran out of hives. (Virginia will start another bee giveaway in July.)

Tignor, 60, grew up spending time on his grandfather’s Hanover County farm. He remembers when there was a plethora of wild bees in the woods and around farms. “And then in 1996, Virginia had a loss of 40 percent of the beehives and 90 percent of the feral bees, and other states experienced similar losses around the same time. We’ve been trying to build back from that ever since.”

“It’s a lot of different things,” explains Rick Fisher, president of the Virginia Beekeepers Association, a 400-member organization that celebrated its 100th anniversary last year. One deadly intruder, the tracheal mite, has been vanquished, but bees still face increased loss of habitat, predatory wax moths and hive beetles, toxic reactions to mosquito sprays and pesticides, and unpredictable climate change. “Last year we had some warm weather and then some really dramatically cold weather for a couple of weeks. A lot of bees, coming out into spring, they’ll start expanding their populations. With a sudden cold snap like that, they can basically starve.”

Then there’s the Varroa mite, an ugly little parasite that can shorten the lifespan of the bee, weaken the hive, and carry viruses. “Globalization is a concern,” says Robert Howard, president of the Roanoke Beekeepers Association. “When problems come from other sides of the world that our bees have never seen, like Varroa mites, they have little resistance. Last year, I knew beekeepers who kept 50 hives and none survived. When you have those kind of losses, you don’t necessarily just bounce back.”

“We lost 13 or 14 hives last year,” Streich says, putting on protective gear so that he can check his bees. “That’s not bad, considering the total number we have, but one neighbor had 16 hives and took a 75 percent hit.” He sighs. “You put all of this work and time into your bees and they die in the winter, or wax moths get in there. One time I had a bear come up and wipe out seven or eight hives. It’s devastating.”

Photo by Adam Ewing

The Thing About Bees

Erika Frydenlund, 38, says that keeping bees is not like caring for a dog or a cat. “Bees don’t care about me. Sometimes they really don’t like me,” she says.

Frydenlund’s 15-acre Portsmouth backyard normally has two or three hives, but she’s currently down to one. “Beekeeping is more like rooting for a team, not like having a pet,” the Old Dominion University professor says. “You invest this time, and it’s fun, and you become a part of something bigger. You cultivate them and you watch them like a TV for awhile, going back and forth, and you can see them bringing back pollen, and you really start to root for them, like a sports team.”

She got into the hobby accidentally, when a beekeeping friend had to leave the country and gave away her equipment. “I went to the Tidewater Beekeepers Association Facebook page and asked if someone could help me,” she says. Six years on, Frydenlund is a fully committed member, and the newsletter editor, of the 200-keeper club.

“A new beekeeper needs a mentor,” says Streich, who recently sold his wildlife removal business, giving him more time to fool with bees. “Theycan read all the books they want or go to these classes, but I learned mostly on-hand, and that’s what I’ve taught to people, what works for me.” In his eight years of maintaining hives, he has encountered things that booksdon’t tell you about, such as two queen bees sharing a hive or an entire 60,000-plus colony, with a full arsenal of honey, disappearing without atrace. “I run into something new every day.”

Lucky and Amy Streich tend their bees in Southampton County.

Photo by Kate Thompson

The range of Virginians who keep bees is, Fisher says, kind of amazing. “You find out they are in homeland security or an anesthesiologist or a pipe fitter. The other day, I met a guy who was a judge at the Winter Olympics.” Although Streich’s and Fisher’s wives originally got them started in beekeeping, the hobby has generally skewed to older males. “Now there are more and more women. Thirty years ago, when she started, my wife was one of two in our [Beekeepers Guild of Southwest Virginia] club, and now it’s about half female.”

We should stop right here and warn prospective beekeepers: If you don’t like getting stung, this is probably not the hobby for you. “I couldn’t even tell you how many times I’ve been stung,” Streich says. “When I do a cut-out, and I’m right there at their doorway, they can be fierce. When I’m done, my gloves look like a pin cushion with all of the stingers.” The one thing you definitely shouldn’t do is dress in black, he warns. “They’ll think you’re a bear and eat you alive.”

“There are people who just have a tendency to get stung,” Fisher has observed. “Like horses and dogs, [bees] can be more aggressive to some people than others. I don’t know what it is. Their vision is based on movement, so if you are nervous and moving around a lot, you are more likely to get stung than if you just remained calm and slowly walked away from them.”

Tignor says that when bees are out foraging, they rarely pay any attention to humans at all, “but because they are looking for flowers, if someone is wearing perfume or some cologne that has a floral scent, the bees are going to come over and check you out.”

When it’s dry and there is nothing to eat, Frydenlund adds, “there’s nothing for them to do and so they get more uppity.” Hardships and angry drones aside, she loves her bees. “When you first crack open the hive, you hear that initial hum. And you realize that there’s this whole world, this whole soap opera happening in there. It never gets old.”

Photo by Kate Thompson

A Vital Role

Fully costumed in a protective suit and latex gloves, Streich is checking his hives, one by one. “It needs to be done before winter comes in to make sure they got enough food on ’em.” The bees—as many as 60,000 per unit—commingle in square, open-bottomed boxes stacked on top of each other, an expandable system should the little guys need room to grow.

Streich opens the top and uses a small pump smoker to distract the bees while he works. They are active, scurrying, circulating, but not in attack mode. He scrapes off some hard, sticky goo—a mixture of honey and wax called propolis—that the bees use as a hive sealant. (This glue-like substance is said to have numerous medicinal benefits.) Pulling out a wooden frame from the box that is fully coated with bustling buzzers and honey, he smiles. “That looks good. That’ll get you a ribbon at the state fair right there.”

Honey bees aren’t the only game in town, of course. There are nearly 20,000 documented bee species across the globe, including the indigenous favorites bumble bee, sweat bee, and mason bee. “The mason is a small, stingless bee,” Fisher says. “You keep them in the garden for pollination. They are small, easy to maintain, and they don’t fly far from where their nest is.” He adds that some of the so-called solitary bees are specialists and only pollinate specific plants.

“That’s why honey bees are so important,” Tignor adds. “They pollinate a wide variety of plants and fruits, and they are available early in the year, in late February and early March, when the flowers are in bloom, and when there are few pollinators out there. The solitary bees are out pollinating for a very short time, five to six weeks in May or June. But with honey bees, you can move their beehive around to wherever you need it, across the country if necessary, and pollinate specific crops. They are active the whole year.”

The bees’ work is essential to the foods we eat every day, he reminds. “Pumpkins, watermelons, strawberries, apples, peaches—but they are also going out to our forests, wetlands, meadows and pollinating our plants there and stabilizing our environment.”

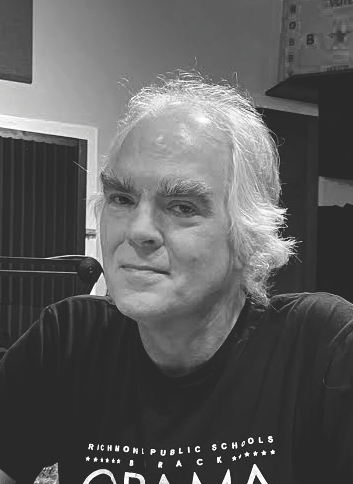

Lucky Streich

Photo by Kate Thompson

Besides pollinated gardens, Frydenlund notes another clear advantage to beekeeping: honey, hundreds of pounds of it. “Even with beekeepers that are just a few miles away from each other, the taste and the color can be totallydifferent. If you just taste honey byitself, it’s just honey, but when you taste different kinds side by side, you startto notice the difference. I think if bees find something they like, they just eat that thing until it’s gone, so that accounts for the variety.”

Is being a beekeeper in Virginia any tougher than in other parts of the country? Howard says he’d give the Commonwealth “a five or a six out of 10” on the bee-keepability scale. “The big problem in Virginia is the availability of plants. You are always trying to keep bees fed so the nectar is flowing at its maximum. And unfortunately, in the middle ofsummer in Virginia, there’s nothing for bees to eat. Some places don’t have that problem. That being said, in Virginia,we still produce honey, we still make wax. But we have to manage our conditions.”

You talk to any farmer and the hope is that things will get better, Tignor says. “You have good years, you have bad years. Now last year was bad, but the bees look stronger this year going into winter than we’ve seen in a long time.” We can attribute this, he says, to recent heavy rainfall. “All that rain is producing a lot of nectar flow in the fall, and we haven’t seen that in a number of years. It provides a food source for bees to build up the population and also store up some for the winter so they can survive.”

Streich pulls out several frames and examines them, pointing out the larger queen, which is marked with a yellow dot, and showing off parts of the hive. Honey drips off the frames, there are no pests, and the young look strong. “Look here,” he says. He shows me a solid frame of incubating dots. “Look at all of that brood. Those are all baby bees that are going to be hatching before the winter.” He beams like a proud father. “That makes me happy.”

This article originally appeared in our February 2019 issue. For products by Virginia beekeepers, click here.